If you’ve ever thought about why you made certain decisions in the past, you’ve engaged in metacognition. Metacognition, commonly called “thinking about thinking,” is a central component of our conscious awareness. Along with its close relatives, “metamemory” and “meta-skills,” it affects the subjective human experience. Take everything here with a bucket of salt because cognitive theories are usually controversial.

What is metacognition?

Metacognition is thinking about and modifying what you’ve already thought, learned, and perceived. Cognition is going through a shopping list. Metacognition is how you later optimize your shopping experiences by planning and evaluating your shopping frequency/budget. It is having cognitions about cognitions while monitoring them in real-time. Two components, “knowledge” and “regulation,” form our metacognitive awareness. The knowledge one acquires by observing their own thoughts is called metacognitive knowledge. Self-reflection, self-awareness, introspection, awareness of personal strengths and weaknesses, and active thinking are common metacognitive activities.

Generally, adding the word “meta” implies second-order processing of what’s already processed (like meta-analysis).

Thinking your thoughts in MEMES and pop-culture references is peak metacognition. Share on X Cognition is thinking, paying attention, and perceiving. Metacognition is thinking about thinking, monitoring one's attention, and evaluating one's perception on purpose. Share on XThe term metacognition was coined by James H. Flavell in the 1970s (Flavell, 1979). While it was originally described as “knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena” (p. 906) in Flavell’s seminal paper, it is now usually defined more briefly but also more broadly as “thinking about thinking.”

Steffen Moritz and Paul H.Lysaker[1]

Examples of metacognition

Planning, thinking strategies, critical thinking, finding motivation, learning comprehension, creative insights, forming beliefs about oneself, introspection (looking inward), interoception (thinking about bodily changes), problem-solving, reviewing study material, creative thinking, conceptualizing learning in the real world with examples, learning algorithms, systems thinkings, goal-setting, browsing problem-solving techniques, etc.

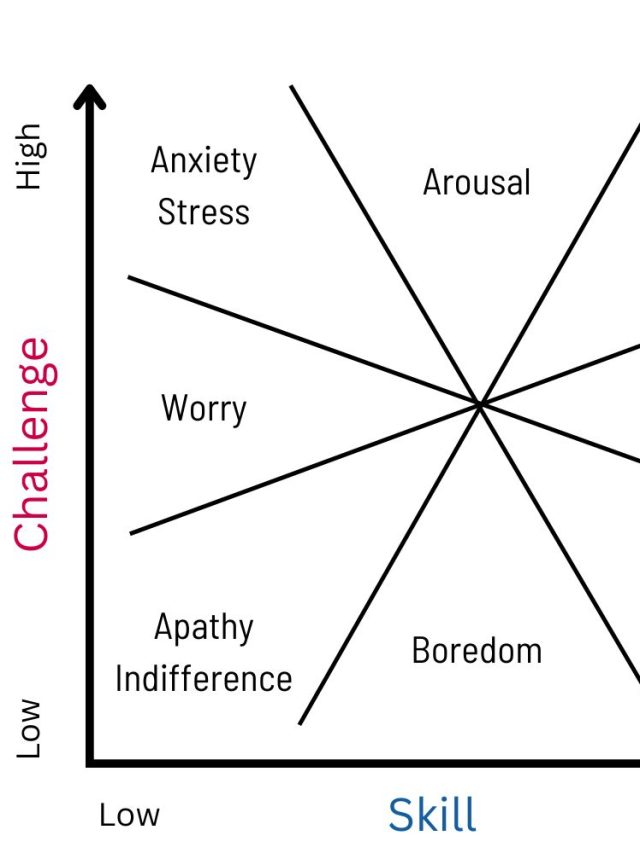

Levels of metacognition

Metacognition occurs on 2 levels:[2]

- The rationalizing level (top level): Evaluation and interpretation of one’s own thoughts and behavior using new ideas, concepts, theories, learnings, perspectives, and mental representations.

Example: Trying to interpret your logic and decision-making – “why am I dating the same type of people and falling into the same patterns?” Then proceeds to date the same kind of people with more technical knowledge about why. You may later evaluate why you dated them and fit your learning about attachment styles, zodiac, reinforcements, shared language, etc., and reassess your experiences in those terms. While deciding to date someone, you’d have cognitions about that person – how they talk, what they share, what you want to say, etc. Later, when you assess them and think about them, you will use metacognitive processes. - The controlling level (bottom level): Using epistemic feelings to modify the associated thoughts and perceptions. Epistemic feelings[3] are second-order emotions that alter cognition in purposeful ways. First-order emotions like sadness, joy, and fear alter them more automatically. Epistemic feelings are curiosity, agency, ownership, familiarity, feeling of knowing something, beliefs, confusion, and doubt.

Example: Trying to change negative thoughts into new perspectives – I am a failure –> I need to rework my skills. Such a change will occur when you have epistemic feelings like ownership of your thoughts and beliefs about what you can do about your thoughts. It would’ve been cognition if you learned it through a blog or therapist. But now that you acquired knowledge about ownership and beliefs, you use them “metacognitively” to address your other cognitions like negative thoughts.

Cognition vs. Metacognition

| Cognition | Metacognition |

|---|---|

| Thought | Thought about thoughts |

| Remembering a fact | Remembering why you remember that fact |

| Sensing | Analyzing what that sensation made you feel |

| Using a strategy | Choosing which strategy is best |

| Random thought | Thinking why you have specific random thoughts |

| Biased attention to big numbers | Correcting your biased attention to notice small numbers |

| Learning a concept | Building its mental representation (mental model) |

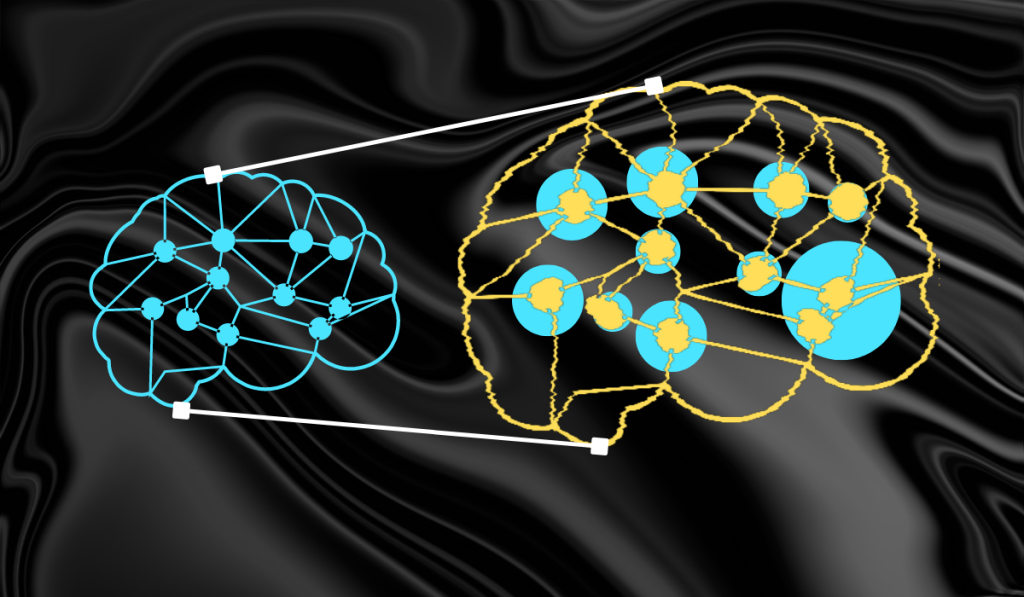

The cognitive aspects are “object-level,” and the metacognitive aspects are “meta-level.” Both levels talk with each other through a flow of information[4]. The flow of information from the object-level to the meta-level is a monitoring process, and flow of information from the meta-level to the object-level is a control process.

- Monitoring processes: The meta-level reads information at the object-level. That means your mind is processing wherever your attention is. E.g., distractions, flavor experience, mindfulness.

- Control process: The meta-level modifies the object-level. That means ideas in the mind control where your attention goes. E.g., emotional regulation, thought-stopping techniques.

Related: What is cognition?

How metacognition develops

Metacognition likely starts to develop at 3 years of age[5] and continues developing throughout the lifespan, with a high burst of development between 11 and 17 years[6]. The current understanding is that metacognition develops in many specific domains and converts into a generalized ability. The foundation may be symbolic languages, spoken language, and theory of mind[7] (source of empathy). For example, a child would learn metacognition (adjusting oneself, decisions, movement planning) in the context of toilet training, eating, play, or hurting oneself and then generalize them into a global set of “self-regulation” tools over time. These are then applied across all domains, even new ones, without learning them on purpose. Arranging toys may translate to arranging food on a plate, for example. At around 15 years of age, metacognition significantly jumps[8] from specific to general. The jump coincides with the end of primary education, which both fosters and promotes metacognition. People still acquire specific metacognition skills in specific domains, like in math class while thinking about Geometry. Essentially, metacognition retains its domain-specific elements and incrementally improves generalized metacognitive awareness that can deploy those skills.

Metacognition likely develops directly through very simple processing signals in the brain[9]. Feelings of curiosity, interest, and lack of knowledge are directly based on the brain giving a signal that there is unknown information. Like a website returns Error 404 Page Not Found, the brain also has an equivalent signal. This signal of “not knowing” or “memory search failed” translates to epistemic feelings that start metacognitive processes. Even mental effort and concentration may come from raw brain signals that indicate how many unused mental resources there are. If they are unoccupied, there is an opportunity to concentrate. If they are occupied, it’s not possible. Similar to a webpage saying “connection timed out.”

The signals that create metacognition also create a human tendency called “sense-making,” which itself is a metacognitive process. Sense-making is our tendency to make sense of our experiences in believable ways after they have happened. It is an attempt to convert chaos and ambiguity into patterns by creating or finding explanations we are ok with. This includes rationalizing, re-analysis, and story-making for decisions and why things happened the way they happened. Using astrology to explain events is sense-making. So is using the scientific method.

People generally have theories about how they think – these are their own metacognitive theories[10]. One could say they are very introspective and they learn only when they get the time to introspect. Or one could also say they need hands-on experience because their memory is terrible. Likewise, people’s views on consciousness, spirituality, philosophies, or how the mind operates are meta-cognitive theories developed through their epistemic feelings combined with life-long learning.

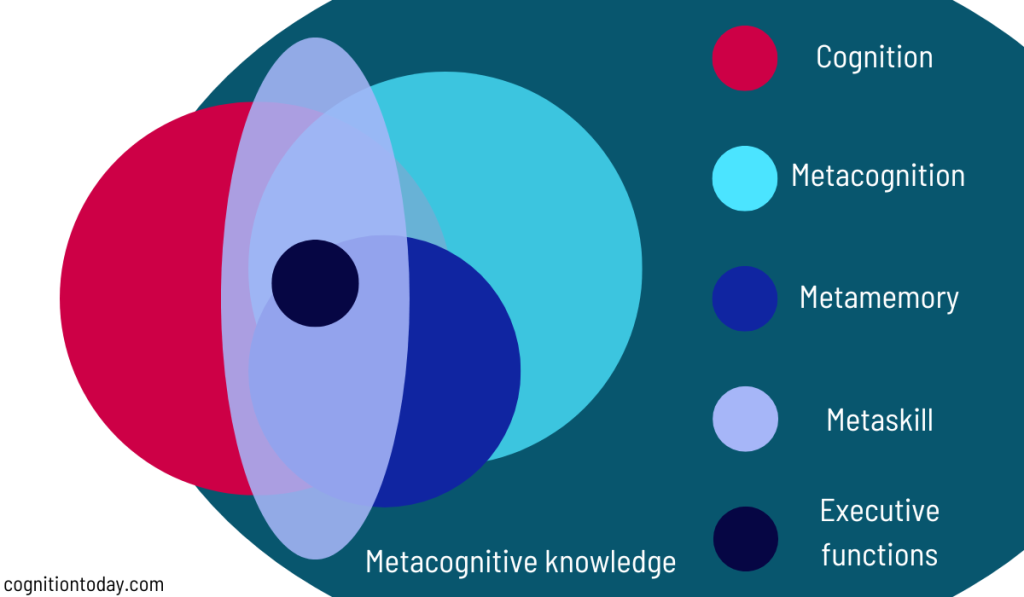

Metacognition can be considered a process of evaluating cognition as understood by the person. When visualized, labeled with words, or conceptualized, its outcome becomes metacognitive knowledge. However, cognition, metacognition, and metacognitive knowledge overlap with blurry boundaries. Pinpointing the differences is still a scientific debate. The overlap could be what psychologists call “executive functions.” They are reasoning, decision-making, planning, problem-solving, and monitoring.

Metamemory

A special part of metacognition is metamemory – Knowledge about the properties, details, functioning, and capacity of one’s own memory. The simplest form of metamemory is knowing you have a memory without remembering the details. If you’ve ever experienced the tip-of-the-tongue phenomena (you can’t recall a memory but know you have it, like a movie’s name), you’ve concluded you have a memory via your metamemory, not actual memory. From a computer programming point of view, it’s knowing there is (or isn’t) an item in a database without actually looking it up, like looking at only the key or value in a pair. Metamemory is also similar to a file’s meta-data on the internet.

All humans have the capacity to quickly figure out[11] what they know and don’t know, and their judgments are quite accurate. For example, without searching the entire mind for all memory units, we can easily tell if we know the answer to a question in an exam. We can look at the question paper and quickly assess what we know without going through the details of what we know. This may seem paradoxical at first, but it isn’t – how can we know what’s in a drawer without checking it? Humans have multiple representations for memory that indicate whether a memory exists or not and to what extent. For example, artificially triggering[12] a small set of neurons that are attached to a memory can activate a larger network of neurons that hold that memory.

Metamemory has 8 unique[13]types of details about memory:

- Strategy: Knowledge of memory techniques and tricks to aid memory. This would prompt you to use a strategy or learn a strategy for specific goals like studying, such as mnemonics to learn biology.

- Task: Knowledge that a task demands memory and recalling ability vs. familiarity or on-the-go analysis. This would prompt you to know how you can do a task if it needs memory or analysis or both.

- Capacity: Knowledge about one’s overall/general memory capacity. This would reflect an accurate understanding of what you are good at remembering, what you are bad at, and where you have gaps in memory.

- Change: Knowledge about how one’s memory changes over time or in different circumstances. This would reflect an accurate understanding of what you could remember well as a child, or what you got good at as an adult, and how that has changed over time.

- Anxiety: Knowledge about how anxiety (and stress) affect memory performance. This would prompt you to pass judgments about how you might not remember something important during an interview because of nervousness, and then you may decide to focus more on those details that are prone to slip your mind during stress.

- Activities: Knowledge of what activities support memory. This would prompt self-reflection about how your memory might be affected by lack of sleep or diet. Here’s a list.

- Achievement motivation: The motivation and intention to maximize memory potential. This would reflect the motivation and confidence to perform memory tasks better when taken seriously vs. casually.

- Locus: Knowledge about how much control one has over their memory (little control vs. high control): This would contain beliefs about how well you can improve your memory or how easily you can lose it with your own actions (such as drinking or no exercise) vs. how easily you believe genetics play a role or you can’t change your memory abilities beyond a small limit.

Metamemory is an important factor for age-related memory decline. Older people often start with subjective memory concerns (SMC), which are then screened by a doctor. 2 aspects of meta-memory – capacity and change[14] – usually indicate the need for medical guidance.

For more on how memory systems in the brain work, look here.

Theories of metamemory

Multiple theories explain different aspects of metamemory.[15]

Cue-familiarity hypothesis: Information is stored as a pair of Cue (a heading, label, trigger, question, concept, etc.) and a Target (the details). For example, the concept of a car is stored as a cue with the label “car” and the target, which contains the details like 4 wheels, driver, steering, etc. Humans might only recall a cue and judge if they have a memory for details. So if the cue is familiar, they know they have the target information. Remembering a familiar process but being unable to recall the details indicates the cue is a “model” and the target is the details.

The accessibility hypothesis: Information is judged based on how easily it is accessed and processed. Easy processing and access lead to more accurate judgments about knowing the actual information. For example, if one is asked, “do you know what gravity is?” they would rely on the most accessible “portion of information” like how planets move around the sun and conclude they know the concept. This theory suggests retrieving a small portion of information because it is easy and accessible creates metamemory judgments of knowing, as opposed to just recognizing if “gravity” is a familiar term (the cue-familiarity hypothesis).

The competition hypothesis: The brain gets constant inputs from various senses and within itself. These create competition within themselves and fight for processing power in the brain. When the competition is high, metamemory judgments about knowing something are inaccurate or low. This might happen because high competition would lead to multiple cue and target activations which create confusion. So low competition would increase confidence in memory. It would be easy to say, “I know what love is,” but when asked, “how is it different from compassion or lust?” one would find it difficult to differentiate the 3. This extra activation of competing inputs fighting for the brain’s resources would make recall worse.

The interaction hypothesis: This theory suggests cue-familiarity hypothesis is the preferred mode for metamemory and the accessibility hypothesis occurs only when cue-familiarity fails. In the car example, one would instantly know what a car is. But when asked “what is a 4-wheel drive,” they would take time to retrieve partial information about a 4-wheel drive, if it exists, and then judge if they know or don’t know.

How metamemory affects daily thinking

Metamemory creates important judgment about awareness of knowledge that affects everyday experiences and overall metacognition.

- Feeling of knowing: We often know what we know in an instant.

- Judgments of learning: When we learn in a classroom or in training, we often accurately judge if we did or didn’t learn.

- Knowing what you don’t know: When asked about an unknown concept, we can instantly judge if we don’t know it, even if the words are familiar.

- Knowing what you know: We are typically confident about what we know for sure, like our name and birthdate.

- Feelings of knowing vs. Actually knowing: Sometimes, we judge information based on familiarity (the cue) but not the proof of memory (successful recall of details). These judgments can create a false metamemory of knowing something because the actual information is unknown or unrecallable.

- Tip-of-the-tongue (presque vu): When trying to recall a specific name or a TV episode, you might forget it even when you have seen it and know you know it. One reason is its memory may be blocked through competition from all other names surfacing in the mind, but its metamemory might be active. Generally, waiting for other memory units to fade out from the mind brings the “target” memory into awareness.

- Prospective memory: Prospective memory describes how we can make a mental note to remember something and then actually remember it later, without repeating the information. This skill is important in planning.

- Dunning-Kruger effect: Judgments of knowledge are less accurate for those who know a little compared to those who know more. But for those who know very little, their confidence is disproportionately high. This may be due to the competition hypothesis (no knowledge = fewer knowledge cues = low competition).

These can be improved with practice and confirmation of accuracy using feedback or verifying knowledge. Eventually, the verification reinforces that memory itself. (sometimes called the testing effect – information you test and verify is remembered better, and other times, called the production effect – information directly produced by your senses is remembered better).

Meta-skills

Meta-skills[16] (aka metacognitive skills) are skills that facilitate learning other skills or skills that develop as an offshoot of other skills. Learning vocabulary and good grammar would be a hard skill, but using it appropriately for general communication would be a meta-skill. Research is a meta-skill of searching for information on top of the hard skill of knowing how to Google well. Learning how to learn ideas are meta-skills that are applied to studying a particular topic.

Meta-skills also refer to higher-order skills you learn while solving problems. For example, planning is a meta-skill that develops through various experiences in planning trips, meetings, house parties, etc. Using specific chess moves and knowing how to use those moves as a metaphor in business is also a meta-skill. These skills, or their versions, can be useful in different areas.

However, the word meta-skills is also interchangeably used with metacognition depending on the context. For example, on LinkedIn, posts about meta-skills could refer to high-level business management skills. In the learning sphere, meta-skills would refer to methods of reflecting on what one learns (essays, commentary, self-reflection, hypotheticals, etc.) Generally, the most common meta-skills described in most domains are about are planning, evaluation, monitoring, strategizing, and execution.

The “strategy” component of metamemory (using memory techniques), is a meta-skill. For example, a person who loves history might develop a good memory for remembering dates and chronology. The same ability might help them remember OTPS or other numerical details if they think of them as dates. Meta-skills can also develop as a part of expertise that can be applied within a domain. For example, musicians learn typical structures of songs and develop memory systems to capture musical structures, which are generally helpful in learning more musical structures. These are memory “schemas” or “templates” or “filters” of musical meta-skills. Metamemory strategies or metacognitive knowledge can respectively re-enter the memory store as procedural memory or declarative memory.

How metacognition, metamemory, and meta-skills affect us

Learning/education: Studies across domains and levels of education say metacognition is a central aspect of quality learning. The brain-based learning system, inquiry-based learning system, and learning how to learn approaches emphasize metacognition as an “active ingredient” in learning. This happens because metacognition allows deeper connectivity between concepts, examples, and facts, and deeper information processing[17]. Similarly, metamemory allows appropriate judgments about learning capacity, and meta-skills become background tools that improve learning. The end result is better problem-solving and knowledge acquisition.

10 ways to improve metacognition while learning are:

- Allow time for thinking and reflecting

- Ask questions and encourage others to ask questions

- Have open-ended discussions

- Recognize strengths and weaknesses in different learning/performance contexts

- Learn specific and broad learning strategies, thinking strategies, problem-solving methods, problem-framing methods, and investigative methods, with examples and demonstrations

- Use prompts and cues to steer a discussion or practice routine

- Promote epistemic feelings like curiosity and interest

- Explore many learners’ and experts’ logic, train of thought, and strategy

- Explore insights from multiple perspectives and relate them to past knowledge and real-world applications

- Mix purposeful planning and strategizing with improvising

- Build realistic confidence in memory and trust in learning capacity, metamemory, teaching capacity, and performance in tests and real-world problems

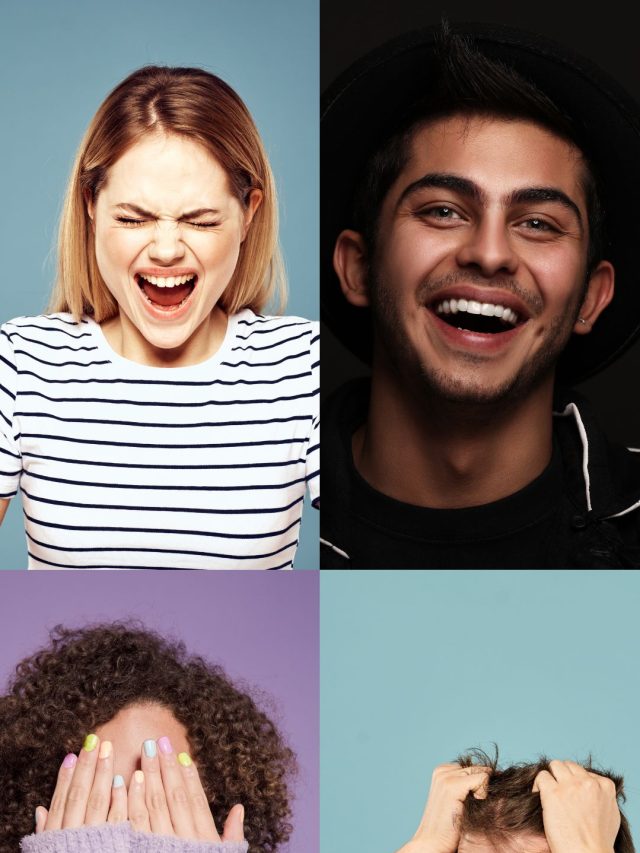

Mental health: Metacognition is a vital component of therapy because all forms of self-reflection, mindfulness, and introspection are metacognitive by nature. Overthinking, negative thoughts, wishful thinking, harmful attitudes, and rigid beliefs about the self and the world are metacognitions[18] that affect mental well-being. Health anxiety and social anxiety are also primarily metacognitive problems. And so is anger and lacking a sense of identity. It also has unique deficits in specific disorders. Metamemory’s change and capacity components decline with age and indicate age-related memory loss, dementia, or Alzheimer’s. Metacognitive deficits like low self-awareness about one’s own attention are seemingly unique for ADHD people[19]. Schizophrenia[20] is also conceptualized as a large deficit in metacognition, that leads to an incoherent reality. Generally, the mental experience of most mental health issues has a metacognitive problem. Some of the metacognitive limits can be controlled by dedicated attempts to self-reflect, monitor behavior, record behavior (journaling), and listen to feedback from close ones.

Social/Interpersonal: Metacognition’s most important aspect from a social point of view is introspection – looking inward + self-reflection. Introspection allows us to modify our behavior and choose appropriate behavior when we have to. For example, introspection can help you analyze why you fight with a partner and change those patterns. It allows self-reflection that can uncover your motivations and reasoning. Self-growth requires monitoring habits, behavioral patterns, and mannerisms, which may be damaging. So for general social health, introspection is a useful tool.

Effectively, all of these processes put together make metacognition a large portion of our entire conscious experience.

Sources

[2]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11406-010-9279-0

[3]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606046/full#

[4]: http://www.imbs.uci.edu/~lnarens/1990/Nelson&Narens_Book_Chapter_1990.pdf

[5]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11409-020-09231-x

[6]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3719211/

[7]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1041608096900205

[8]: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/17910

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0010027722001056

[10]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02212307

[11]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0079742108600535

[12]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.3592

[13]: https://academic.oup.com/geronj/article-abstract/38/6/682/586706

[14]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6779492/#

[15]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-00111-013

[16]: http://informationr.net/ir/25-4/isic2020/isic2010.html

[17]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035598/

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006322321013299

[19]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00702-020-02293-w

[20]: https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article/40/3/487/2338250

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to paint a holistic picture of psychology. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, Entrepreneur, Lifehacker, about 15 books, academic courses, and 100s of research papers.

I’m a full-time psychology SME consultant and I work part-time with Myelin, an EdTech company. I’m also currently an overtime impostor in the AI industry. I’m attempting (mostly failing) to solve AI’s contextual awareness problem from the cognitive perspective.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology).

I’m based in Pune, India. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.