The psychology of social media (research summary)

- Social media allows a way to manipulate how you present yourself. Many choose to show an overly positive, quality life. Some choose to highlight victimhood. Self-presentation and self-expression are innate psychological needs that social media satisfies. Knowing this, judging yourself based on others creates an opportunity for negative social thinking based on a mere illusion.

- It’s not always the frequency and duration of social media use that matters the most. The type of social media activity and how people deal with social media stress can affect mental health more.

- Social media does not necessarily harm mental health. Its effects can be positive and negative based on what a user does on social media.

- Bad psychological effects of social media emerge through negative social cognitions like social comparison, FOMO, and associated cognitions like poor self-esteem and poor body image.

- Good psychological effects of social media emerge through positive behaviors like seeking out entertainment, sharing creative content, nurturing relationships, seeking out like-minded people, etc.

- The type of content in your newsfeed can affect the type of content you post on social media. A positive newsfeed promotes positive interactions and a negative newsfeed promotes negative interactions.

- Personality affects a user’s type of social media activity. High agreeableness and extroversion are associated with online selfie interactions, and neuroticism, introversion, and conscientiousness are linked to problematic social media use.

- Loneliness, fatigue, cyberbullying, poor sleep, social media stress, social exclusion, etc. are some evidence-based pathways that link depression and social media.

- Not all active social media use is good and not all passive social media is bad. However positive-active use is more likely to be good for you and negative-active use is more likely to be bad for you.

- Venting, ranting, and posting emotionally loaded updates can lower self-esteem & mood but posting daily activities can improve your self-esteem & mood.

- The relationship between psychological well-being and social media use is complex and non-linear with mechanisms that contain both real-life and digital-life elements.

- Memes are advanced emotions.

Long article. Table of contents below.

The mobile phone scrolling posture – Head down, finger on the mobile screen, and micro-expressions on the face – is an iconic human posture. That’s our social media posture. Is it iconic enough? Yes. 4.4 billion people[1] use social media on their mobile phones (as of July 2021). This brings us to a new field of study called cyberpsychology and we are just starting to understand how social media affects us psychologically.

Social media has both positive and negative effects on mental health and well-being.

Social media is defined as a digital framework that enables “a way for individuals to maintain current relationships, to create new connections, to create and share their own content, and, in some degree, to make their own social networks observable to others.” (given by Jeffrey W. Treem, Stephanie L. Dailey, Casey S. Pierce, Diana Biffl[2])

People use Facebook, TikTok, Telegram, Instagram, Youtube, 9Gag, Snapchat, and Twitter (sorry, G+) to rant, show off, advocate social justice, discuss politics, give ground-breaking opinions, etc. Wait. That’s not true, is it? Perhaps, it’s just to feel safe and connected, Just having a phone with you can function as a security blanket[3] even if you don’t use it. Researchers say that it buffers against feelings of social exclusion and can be a coping mechanism for social stress & anxiety.

- How active are we on social media?

- Mental health and the type of social media use: Active, Passive, Positive, & Negative

- Personality and social media behavior

- How is social media linked to depression, anxiety, and well-being?

- Behavior and anxiety in real-life vs. online-life

- Bedtime social media, sleep, and overthinking

- Memes, Mental health, and Well-being

- Sources

The majority of social media users spend time scrolling and consuming content with minimal social interactions. The engagement rate (likelihood of a person interacting with a post) is as low as 0.08% on Facebook, 0.98% on Instagram, and 0.045% on Twitter[4] per post as of 2020 end. This interaction is a baseline for any social activity over and above interactions within closed chat groups. These tiny percentages are all human-generated likes, hearts, retweets, comments, shares, status messages, posts, etc. + some bots on IG. The numbers show most social media use is passive, but a lot happens with active use.

Active social media use: People actively interact with other people on social media. The stats above reflect active use.

Passive social media use: The majority of social media activity is scrolling through feeds and consuming content.

Active and passive social media use is a practical classification to understand how social media affects us psychologically. People use social media actively or passively for a number of reasons – instant gratification, relaxed entertainment, keeping in touch with known people and nurturing existing relationships, seeking validation, protecting self-esteem, an opportunity to create a new version of themselves, getting in touch with new people, voicing an opinion, escaping for existing problems, procrastination, boredom, information consumption, making new friends, etc. And they use various sites for that – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, WeChat, etc.

Passive and Active use

Research on 10,000+ Icelandic adolescents (2019)[5] shows that passive social media use is associated with a self-reported increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms and active social media use is associated with a reduction in depressive and anxiety symptoms. And, active social media did not increase emotional distress, which one might assume increases due to negative interactions. They also found that passive use by women is more strongly associated with poorer mental health. These effects were seen even when the amount of time spent on social media, self-esteem, offline peer support, and poor body image are taken into account. However, an Icelandic population, like any national demographic, can’t be generalized to represent the entire digital culture.

An online survey research study[6] on 702 American Reddit recruits also found an increase in passive social media use was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms and an increase in active social media use was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms.

Social media use can create many opportunities for jealousy and comparison with others only to judge oneself on that comparison. Social media use also permits modifying self-presentation to a great extent. We see this behavior as typing and retyping a status message on Facebook or taking time to consciously think about how and what to reply after reading a comment notification. This could lead to deliberate bragging or thought manipulation on social media which not only affects the bragger/manipulator but also the ones who are viewing it.

A longitudinal study that analyzed Facebook user activity[7] (active and passive not separated) found that an increase in Facebook likes, link clicks, and status updates meant a decrease in well-being. But, a systematic review[8] concludes that social media use also positively impacts our well-being. After looking at the experience of social media users[9], we see some patterns. Their study found those who posted about daily activities had a better mood and higher self-esteem, and those who ranted or stayed emotional on social media had worse moods, higher paranoia, and lower self-esteem. Those who thought they are lower in the social hierarchy also tended to have more paranoia and low self-esteem along with a worse mood.

Posting too much on social media may be psychologically unhealthy depending on the content you post. There is a moderately controversial notion that catharsis can make things worse[10]. Rumination and venting can bring undesirable thoughts and feelings into awareness which may continue to negatively impact one’s mood. Active social media use may stem from a tendency to participate and engage with a community – which is linked to an increase in subjective well-being.

FOMO and active use; Social Comparison and passive use

Active social media users often share stories, opinions, discuss issues, and converse. This may stem from a lower baseline anxiety level. This does not indicate that passive social media users do not have stories or opinions to share, their choice to not share may stem from a variety of other psychological reasons such as fear of judgment, ridicule, or the fear of showing vulnerabilities. This is also amplified by the need to counter the fear of missing out (FOMO) – we feel compelled to do what others are doing just because they are doing it. FOMO is a negative feeling that may push us to do something we don’t want and still highlight how we are dissatisfied because we are missing the fun.

Research shows that FOMO and social comparison[11] play a role in linking depression, negative self-perceptions, and passive social media use. Social comparison comes from comparing ourselves with others and evaluating how we stack up against them. Are we better? Are others better? We determine our self-worth based on how others are; but on the internet, most people often portray their best side, exaggerate the normal stuff, and hide the negative side. That leads to comparing our average self with others’ exaggerated positive self. This creates a negative self-image or a narcissistic self-image based on what gets compared and how one evaluates their self-image.

There is another way to classify social media behavior/interactions: Positive & Negative social media behavior in the context of depression[12]. Positive behavior can improve well-being, reduce depressive symptoms and negative behavior can worsen depression, anxiety, or life satisfaction. Negative social behavior like sharing risky content, social comparison, etc., is linked to deteriorating well-being. Positive behavior such as seeking out entertainment, creative content, and nurturing relationships has no negative impact (neutral activity) or can buffer against mental health issues. Social comparison is generally bad in real life and online. However, it’s not all bad. There is some evidence[13] to show that social comparison based on ability can hamper psychological well-being and social comparison based on opinions can improve well-being.

One might wonder how personality affects the type of social media activity. Data from 20,000 people from 20 countries[14] shows that there is a mild relationship between personality and social media use. Researchers found a number of correlations between specific types of social media use and personality traits. Extroverts tend to use social media to consume information and socialize. Emotionally stable people tend to use social media for most activities but with lesser frequency. People with neurotic traits (prone to anxiety, mood swings, envy, etc.) tend to spend more time on social media to socialize and consume information. However, these results are not straightforward. The relationship between social media use and extraversion is non-linear[15], and possibly, U-shaped. So, being introverted or being very extroverted might increase commenting, liking, browsing, adding friends, etc., but being ambiverted or moderately extroverted might mean you don’t engage much on social media. Introverts might increase social media engagement because of the distance and reduce social anxiety because social media is less confrontational and extroverts might reflect more social engagement because it is also high in real life.

Online personality vs. Offline personality

Both personalities are unique and context-dependent. The online disinhibition effect explains this quite well – Online personas are different from real-world personas because the internet offers anonymity and psychological distance that allows us to lower our filters, increase impulsivity and aggression, and drop inhibitions. People tend to self-disclose[16] more because of perceived invisibility. The lack of real-life feedback (eye contact, physical presence), the shrugging of responsibility, the invisibility, the digital mask & shield, the ability to trivialize consequences, etc. can make people do things they wouldn’t normally do in the offline world. But, both are equally “real” versions of the self.

Personality traits and why people go online

When it comes to comparing personality traits and social media addiction, the issue is a little complex. Extraversion (out-going, social) and neuroticism (prone to negative thoughts, anxiety) are both linked to social media addiction via different mechanisms. Both traits increase status update frequency on Facebook. Probably because Facebook offers to fill the psychological need for self-presentation and enable self-expression. Moreover, for extroverts, the positive feedback received online (such as Facebook Likes) can promote social media use by fulfilling an additional need for engaging in positive social interactions. This conclusion is significant but statistically weak[17]. And, it cannot be generalized because these patterns emerge in people who are already motivated to use social media – the study didn’t account for those who are inherently unmotivated to use Facebook.

Multiple studies have looked at how loneliness, narcissism, and low self-esteem affect social media use. A meta-analysis of 80 studies[18] shows that social media use is higher in people with low self-esteem, high narcissism, and high loneliness. Online lurkers (people who view but don’t interact; passive anonymous social media use) are likely to have low self-esteem. On the other hand, people with high self-esteem are likely to have more friends online but not anonymously lurk. Researchers also found that high narcissism is linked to a higher friend network and a variety of active social media interactions like commenting, sharing photos, and updating status posts.

Personality and behavior[19] are intertwined with the selfie-posting culture. The tendency to be warm and friendly (agreeableness) and be social (extraversion) is associated with commenting and liking other people’s selfies. Being conscientious and neurotic is associated with a tendency to get involved in other people’s responses to their selfies. People (especially females) who are conscientious, agreeable, neurotic, or introverted are likely to experience problematic social media use[20]. (Facebook addiction, pre-occupation with others’ social media profiles, compulsive meme sharing are examples of problematic social media use).

The same study employed the uses and gratification framework to understand why people use social media. They found that those who exhibit a degree of problematic social media use are motivated to be on social media (Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram) to keep in touch with friends, meet new people, display or create a more popular version of themselves, gain entertainment, or pass time. Gender differences also emerge from the existing literature. Women exhibit higher problematic social media use than men and use social media to maintain existing relationships while men use it to meet new people and potential short-term mates. Younger people (the current youth/teens and young adults), on the whole, have a broader set of motivations and types of social media activities as compared to older people.

A personality trait called sensory perception sensitivity is closely linked with well-being if a person chooses solitude and takes social time-offs. There is a separate article on that, so I recommend reading that for all the details.

Social media and empathy

A study on 942 Dutch adolescents[21] suggests that social media use can promote psychosocial development (interpersonal and behavioral aspects). Researchers found evidence to support the idea that social media use improves 2 types of empathy – cognitive (understanding other’s perspective) and affective (understanding other’s emotions). One explanation for this is that social media use sensitizes people to others’ perspectives and presents an articulated way to comprehend them (status updates, memes, shares). More on how to improve empathy here.

The amount of time someone spends on social media doesn’t necessarily mean poor mental health, it’s only the activity type that matters. Considering how fresh the research is and the fact that no cohort exists today whose social media use can be assessed for lifetime influences, it’s too early to blame social media for poor mental health. One example of the problems in finding a cause-effect link is how participants are recruited. In a study on Korean students[22] who were recruited via advertisement fliers across a university showed that depressed individuals were less likely to have social engagement like location tagging and fewer Facebook friends. The mode of recruiting may create a selection or survivorship bias where those extremely passive in real-life might not participate.

A common misconception is that routine social media use negatively affects social life and mental health. New research[23] on a nationally representative American sample has found evidence for the exact opposite. People who routinely used social media for social engagement had better social well-being, positive mental health, and self-rated physical health. However, those who used social media because of FOMO or a feeling of disconnect had lower social well-being, mental health, and self-rated physical health. This study suggests that routine social media use is a reality for people (and not an escape from reality). Being active helps people have shared experiences, things to talk about, low-effort limited access to social things, etc. It’s fair to conclude that for those who want to, routine use improves life satisfaction. The study also shows that an unhealthy emotional attachment to social media is at the core of negative effects.

A systematic research review paper[24] from 2019 suggests that the time spent on social media, the type of user activity, the investment in social media use, and the level of social media addiction are associated with psychological distress, depression, and anxiety in adolescents. A review from 2014[25], concluded that there is no evidence that social media use causes depression; but many possibilities exist where there are feedback loops between the two.

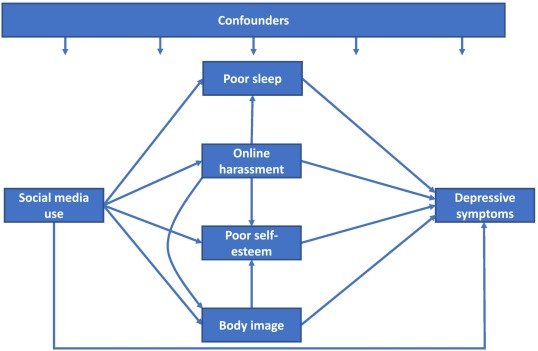

One potent mechanism in how social media use is associated with depression is given by Yvonne Kelly, Afshin Zilanawala, Cara Booker, and Amanda Sacker[26]. The study analyzed social media activity and its role in depression in a nationally representative UK Millenial sample of 11,000 adolescents (1:1 male-female ratio).

They found 4 prominent mechanisms which tie depression and social media use together – poor quality of sleep, online harassment/cyberbullying, poor self-esteem, and body image issues. There were no gender differences in these pathways which link the two.

These factors form multiple feedback loops between events and experiences in real life and digital life. The authors do not claim that social media use causes depression. They only identify consistent pathways which link the two and these pathways may function as causal factors in individual clinical cases.

In parallel to these findings, researchers have also uncovered other pathways between problematic social media use and depression/poor mental health[27]. Loneliness and fatigue is related to long-term problematic use and problematic use is also linked to loss of interest and concentration. However, when researchers tried to isolate the contribution of problematic use by controlling other related variables, they found no relationship between depression and social media use. Expanding upon this baseline, there is some evidence that shows[28] personality traits like antagonism (hostility) and negative affectivity (negative thinking, poor self-concept) increase the risk of problematic social media use.

For teenage girls, frequent social media use can reduce life satisfaction[29], happiness, and overall well-being because of cyberbullying and a disrupted sleep cycle. This effect is significantly lower in teenage boys. The frequency of use (apart from addiction), in isolation, may have no effect on well-being.

Experimental studies in this area are rare. One simple experiment[30] showed that asking people to limit social media use to 30 mins a day (10 mins for Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat individually) can improve well-being by reducing depression, anxiety, loneliness, and the fear of missing out. The takeaway is actionable – limit social media activity to 30 minutes a day and you’ll see an improvement in your overall well-being in about 3 weeks.

These studies can tell us one thing – the relationship between mental health and social media use is complex and depends on many dozens of factors.

One novel line of research is analyzing the text in social media activities like tweeting. Researchers have managed[31] to extract the symptoms of depression or deteriorating mental health by using machine learning tools on textual data. This line of research shows the value of understanding text to identify the early signs of depression. But that’s not it. This approach complicates the active vs. passive social media use findings. If depression can be detected through textual activity on social media, it is by definition generated by an active user. There is more to be explored here.

We don’t know if early signs are visible via text updates because the users are active with a trend toward passive use – the sample with clinically valid depression may no longer exist on social media with the same usage characteristics. Comparing the texts for clinically diagnosed patients, people who show early signs, and people in remission might yield richer data on mental health and social media use.

Behavior and anxiety in real-life vs. online-life

When it comes to a particular issue like social anxiety, research suggests[32] that online social anxiety is less intense as compared with social anxiety in real life for those suffering from social anxiety.

One parallel between social media behavior and physical life behavior is how users respond to the influence of their peers[33]. For example, they are more likely to hit the like button on posts that have already amassed some likes – likes beget likes just like votes beget votes. Peer endorsement plays a role in modifying the behavior of adolescents – People like what their friends like.

Poor sleep and social media have an unclear relationship[34] with one another where we don’t really know if there is a clear cause and effect. For 11-15-year-old females[35], social media stress appears to increase sleep latency (time needed to fall asleep) and daytime sleepiness. This effect was not observed in males. For students[36], smartphone overuse is linked to sleep problems, anxiety, and depression. Students also tend to have a variety of first-time stressors such as gaining financial independence, domestic independence, dating, skill development, academic demands, and the thirst to have fun which explains mental health issues.

Nighttime social media scrolling[37] can potentially disturb sleep[38] via an interaction between 2 factors – social cognition about social media content and the effect of high-energy blue light from lit screens. Social cognitions include thinking about social information like photos of friends having fun, or a status update on social issues, or reading comments. Studies have speculated that blue light emitted from screens can cause stress and that, in turn, causes sleep problems. In this study, the type of content or blue light filters did not individually affect sleep quality but their interaction did. Specifically, blue light filters were effective in improving sleep only when participants viewed low arousal Facebook content: content that didn’t trigger social thoughts, irrelevant and uninteresting posts (basically, boring content). Under normal viewing conditions, these effects are unlikely to manifest and 15-30 minutes of bedtime social media might not affect the quality of sleep at all.

Memes, Mental health, and Well-being

So far, we haven’t looked at the connection between memes and mental health (although, sharing memes is an active and positive type of social media use). Many of us enjoy relatable memes. These create an opportunity for self-reflection (and laughing at oneself), which, at the very least[39], helps us to ease symptoms of poor mental health. Research on memes also shows that viewing memes can help people manage burnout and cope with stress[40]. The meme-sharing culture is virtually omnipresent and fosters a collective human identity[41]. Wholesome and AWW-inducing content can make us feel good and sharing these moments improve our psychological state. It also helps us develop a small people-meme network within a larger culture.

If we apply the adage “You are what you eat” to social media, we get the notion that the internet gives us a regurgitated version of what we feed it. Emotional contagion (feeling emotions similar to other peoples’ emotions by witnessing their emotions) can spread via social networks[42]. Emotional contagion theories tell us that seeing negative posts in the newsfeed can make us create negative posts and seeing positive posts can make us create positive posts.

A promisingly positive outcome[43] of memes is that clinically depressed people find depressive memes more humorous than neutral memes and they, in fact, improve their mood. Researchers believe that this effect is largely due to the humorous take on negative experiences and relatability which extends to other people who resonate with such memes. The congruence between a depressed person’s mind and the depressive meme’s content can alleviate pain, down-regulate negative mood, and offer an alternative way to manage emotions (healthy alternatives are often difficult for depressed people). There is a good chance that memes can help with depression.

Memes are social, communicable, relatable, and they capture the essence of an experience or a thought. In fact, they do what emotions do on many levels.

Memes are advanced emotions. Memes are social, communicable, relatable, and they capture the essence of an experience or a thought. They do exactly what emotions do on many levels. Share on XSources

[2]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/soc4.12404

[3]: https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/2018/05000/The_Use_of_Smartphones_as_a_Digital_Security.3.aspx

[4]: https://www.rivaliq.com/blog/social-media-industry-benchmark-report/

[5]: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

[6]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326334189_Passive_and_Active_Social_Media_Use_and_Depressive_Symptoms_Among_United_States_Adults

[7]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28093386

[8]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27732062

[9]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/acps.12953

[10]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0146167202289002

[11]: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/12271

[12]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jabr.12158

[13]: http://cel.webofknowledge.com/InboundService.do?customersID=atyponcel&smartRedirect=yes&mode=FullRecord&IsProductCode=Yes&product=CEL&Init=Yes&Func=Frame&action=retrieve&SrcApp=literatum&SrcAuth=atyponcel&SID=F4nOFaykaUmvYX6J534&UT=WOS%3A000417670700010

[14]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321194716_Personality_Traits_and_Social_Media_Use_in_20_Countries_How_Personality_Relates_to_Frequency_of_Social_Media_Use_Social_Media_News_Use_and_Social_Media_Use_for_Social_Interaction

[15]: https://www.sbp-journal.com/index.php/sbp/article/view/7210

[16]: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4335/3402

[17]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306460319306525

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0092656616300721

[19]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886916312545

[20]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6#CR20

[21]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563216303673

[22]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24084314/

[23]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1090198119863768

[24]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

[25]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4183915/

[26]: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(18)30060-9/fulltext

[27]: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/73951

[28]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886919304490?via%3Dihub

[29]: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(19)30186-5/fulltext

[30]: https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

[31]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318136574_Extracting_Depression_Symptoms_from_Social_Networks_and_Web_Blogs_via_Text_Mining

[32]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51885706_Social_Anxiety_in_Online_and_Real-Life_Interaction_and_Their_Associated_Factors

[33]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797616645673

[34]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743516000025

[35]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10410236.2017.1422101

[36]: https://akademiai.com/doi/abs/10.1556/2006.4.2015.010

[37]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjop.12351

[38]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1389945713020194?via%3Dihub

[39]: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/1175/1/012250/meta

[40]: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/499/

[41]: https://firstmonday.org/article/view/5391/4103

[42]: https://www.pnas.org/content/111/24/8788.short

[43]: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-57953-4

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.

Your survey is dope worth its weight in gold.

Thank you 😀 Really appreciate it 😀

Very good article. I’m going through a few of these issues as well..

“System Doom: Chaotic Flights of Fancy”

http://moultonlava.blogspot.com/2005/10/chaotic-flights-of-fancy.html