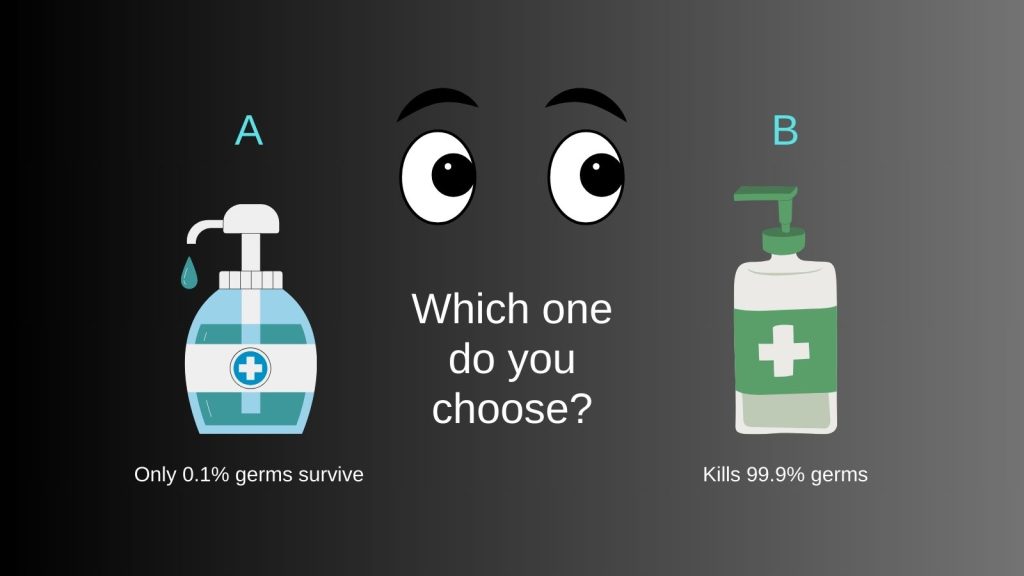

2 options are marketed to you. Choose between Hand Sanitizer A OR Hand Sanitizer B.

Did you Choose Sanitizer B? You are not alone. Most people do. It’s because of the Framing Effect.

The Framing Effect describes how people choose between 2 or more options based on how the options are presented in an advert or marketing message. The context, the imagery, the words, the meaning, etc., of a marketing statement is called a “Frame”. It is, metaphorically, the frame in which the core information of a product is placed. These frames include emotions, words, numbers, images, symbols, cultural elements, contexts, sounds, and identity details. The frame creates a strong influence on the buyer’s decision-making process.

In the sanitizer example, sanitizer B has a gain frame (you gain from the death of 99.9% germs) and sanitizer A has a loss frame (you face the risk of the 0.1% germs that live). People tend to accept the gain frame more readily.

Consider 2 similar products or 2 marketing messages for the same product. Depending on the frame each option has, consumers will favor one of them. Because the creativity in ads and the persuasive nature of messaging have become so competitive, consumers have to take a step back and re-evaluate their decisions to know if they are good or bad.

Framing has 2 goals in marketing.

- Make some options you get as a consumer more appealing

- Make a product look better and persuade you

Framing elements are essentially small components that go into the larger picture of a nudge in most commerce scenarios.

So, as a smart consumer, your job is to understand the product and judge it to be good for you even when the frame is removed from the product’s attributes, uses, cost, features, etc. This way you know you weren’t blindly persuaded and made a good decision.

Let’s first look at the different types of frames used, so you get an idea of what to look for.

Framing Effect: Contextual elements like wording, imagery, colors, culture, identity, sounds, numbers, etc., create a strong bias in favor of a product. Critical thinking, pros & cons thinking, and second-language thinking reduce… Share on XTypes of framing

1. Gain/Loss frame

A loss frame is a message focusing on avoiding a negative outcome.

E.g., You’ll get sick if you don’t eat healthy.

A gain frame focuses on showing a positive outcome.

E.g., You’ll live longer if you eat healthy.

Note: This is also often called positive vs. negative framing or attribute framing. You’ll see some other frames are derivates of this.

2. Emotion framing

Emotion framing highlights a specific emotion in a message. Consider you are marketing a Toolkit for home repair.

E.g., A happy family needs a happy toolkit to protect it. (positive emotion)

E.g., Is your house sick? Repair it with this toolkit. (negative emotion)

Emotional frames can nudge people to show risk-seeking behavior. In one study[1], positive emotions evoked during a decision task led to more risk-seeking behavior. In the crudest sense, feeling positive or optimistic about a decision is related to taking more risks in a risky-choice loss frame. For example, people are likely to make riskier health decisions if they are made to feel positive about a symptom-free life by showing how their suffering will get worse without the treatment. Negative emotions[2] can exaggerate risk and make evaluations pessimistic – expecting worse travel journey, for example. As a result, sad or anxious people may desire certainty more than happy people. While people with negative emotional mindsets tend to choose risk-free options, those with positive emotional mindsets tend to take more risks. So emotional frames that induce strong emotions can guide risk-seeking or risk-averse behavior.

3. Culture framing

Culture framing means including cultural elements in your marketing to appeal to the target audience. Most typical features are:

- Racial & ethnic similarity with the target audience

- Slang & language characteristics

- Religious & cultural symbols

- Aspirations & dreams

- Shared pop cultural elements & references

E.g., Why choose between men’s and women’s clothing? Buy anything you like from our unisex store!

E.g., Include local language phrases, references to specific demographics’ shared cultural symbols

4. Sound framing

Sound framing is the musical context of a message. It could be ASMR, light music, dramatic sounds, metal, etc. The musical context creates a preference.

E.g., 7 Days of the Week time-lapse advert portrays office-goers listening to jazz that transitions to them having an energy drink on Friday night to become adventurers with metal music.

Just yesterday, I reacted with a laughing emoji on an animal video of animals doing silly movements. My friend asked why laugh, its a sad video. I then read the caption and heard the background score. Those were animals in pain. Big oops. I fell for the sound framing and misinterpreted it.

Here’s a famous video of Bruce Lee vs. Chuck Norris with Careless Whisper by George Michael, which makes the video romantic instead of an intense face-off.

Research has documented this repeatedly. There is a “valence transfer” of emotions from music to words and faces. That means happy music can make words[3] and facial expressions[4] (and even paintings, movie scenes, ambiance, etc.) appear happy, but the same words and faces can appear sad when they are paired with sad music. And, similarly, the musical frame can intensify or dilute the emotion associated with a stimuli. For example, rock music can intensify the expected impact of an energy drink, and jazz music can intensify the impact of elegant jewelry.

Retail shops strongly leverage the influence of music on consumers’ buying behavior.

5. Identity framing

Identity framing involves directly stating country, region, political affiliation, lifestyle, etc.

When it matches the consumers’, they are likely to choose that option.

E.g., Democrats are loving this new EV.

6. Price Framing

Price framing is about how the prices, discounts, offers, etc., are listed. This includes the typical nutritional price breakdown strategy of converting the whole product into each use of the product per day or per serving.

- Font size of the price & how much it stands out

- Whether it ends in .00 or .99

- Whether discounts are pure numbers or percentages (and what looks bigger)

E.g., $5 discount vs. 5% off on a $100 product.

Frames can be applied to pricing a product. Price framing refers to how people make different decisions based on how much they are saving as a percentage (30% off) or pure numbers ($8 off). A recent study[5] suggests that consumers prefer pure number savings above $100 and percentage discounts below $100. Discount frames affect how valuable a product is after assessing the value of the discount itself, so higher price tags can evoke a sense of high value if the savings are a large amount. In another study[6], a fixed discount on a high-price product was more attractive to consumers than the same discount percentage on a low-price product, which highlights there is some processing about the total amount saved even if more money is needed to save that amount.

7. Visual framing

Visual framing is the visual context: The colors, people, and objects used in marketing, the vibe, transitions between colors, the design and photography in it, etc. It’s the visual design element.

E.g., Minimalistic black-white message vs. hues of blue and yellow as background imagery for your social media post.

In one study[7], depression-related messages for college students created different reactions from students based on the visuals showing recovery, treatment, or suffering. Recovery-related imagery created more positive emotions while suffering imagery created negative emotions. Recovery messages indicated higher motivation in participants to seek help than the negative imagery.

8. Number size framing

Number size framing gives special attention to the sensitivity of changes in numbers. The difference between 2 and 4 seems larger than the difference between 995 and 997, for example. This framing commonly affects how people react to increases in body weight. 160 to 165 seems like a larger gain in weight than 220 to 225 pounds.

E.g., Writing 20% extra large soap vs. buy 1 get 1 free for a smaller soap.

Consumers choose what feels more instead of what deal is mathematically better.

9. Goal framing

Products use goal framing to tap into a consumer’s goal/desire or the consumer’s intention to avoid a consequence. Specifically, goal framing highlights the benefit of an action or the negative consequence of no action.

E.g., “If you continue XYZ, you’ll suffer from ABC” is a negative goal-framing message that highlights a loss. “If you stop XYZ, you’ll reduce your risk of ABC” is a positive goal-framing message that highlights a gain.

Goal-framing studies[8] typically show that consumers are more willing to avoid a loss than receive a gain. This is seen in bill payments where consumers will pay before the deadline to avoid a penalty instead of gaining a small discount. Goal framing is very similar to gain/loss framing, but, in the consumer world, the goals are particularly highlighted as:

- Improving health vs. suffering from a disease

- Simplifying life with a product vs. bearing the cost of a future problem

- Improving self-image vs. feeling bad

- Saving money vs. earning money

- Purchasing a better detergent for hygiene vs. carrying germs on clothes

- Buying warranty vs. paying heavily during product repairs

10. Attribute framing

Some products highlight their best and underplay their negatives. Consumers then tend to base their decisions on that 1 attribute to make their decision and ignore the negatives.

E.g., “World’s thinnest laptop” is highlighted but the battery capacity is ignored.

Attribute framing simplifies decision-making and forces the consumer to fall in love with 1 attribute that biases them. In reality, there is usually a downside because of physical or economic constraints.

Research suggests[9] some people are more affected by certain frames. When information is framed as a loss, they prefer riskier options. They found evidence for attribute framing and risky choice framing, but not goal framing. Their study suggests consumers are likely to spend 8.02 cents more for a pound of ground beef if it is labeled as 80% lean instead of 20% fat. This is an example of attribute framing. Their study also showed that there was no evidence for gender-based differences in how frames affect decisions and a factor called “need for cognition” (preference to think a lot about information) did not influence framing effects. This suggests framing effects are hard to overcome in typical scenarios.

The classic study

The “asian disease[10]” study done by Amos Tversky & Daniel Kahneman used the context of a disease that could kill 600 people. 2 groups of subjects were assigned to a “lives saved scenario” vs. a “lives lost scenario” representing gain vs. loss framing. In each group, participants had to choose between 1 of 2 treatments that either guaranteed saving a few or risk saving/losing all. The results of their study violated previous economics theories.

Lives saved scenario (gain frame)

- Treatment A (positive & certain): 200 survive.

- Treatment B (positive & risky): 1/3 (33%) probability 600 individuals are saved and 2/3 (67%) probability all die.

71% of people chose option A, a certain gain, even though mathematically, both options saved the same potential lives. (1/3 of 600 is 200)

Lives lost scenario (loss frame)

- Treatment C (negative & certain): 400 die.

- Treatment D (negative & risky): 1/3 (33%) probability 600 individuals die and 2/3 (67%) probability 600 individuals will die.

72% people consistently choose option B. Both options are statistically the same – 200 people are expected to survive mathematically (2/3 of 600 is 400 dead).

Changing the gain frame to a loss frame and people swapped between choosing certain gain to save a small number of people to choosing a risky option to save more people. Just because the wording changed.

The consumer insight here is that they want to guarantee a benefit but take maximum risk to avoid the worst outcome. Prospect theory explains this tendency with a simple human principle – the pain of a loss is greater than the joy of an equivalent gain (losing $100 hurts more than earning $100).

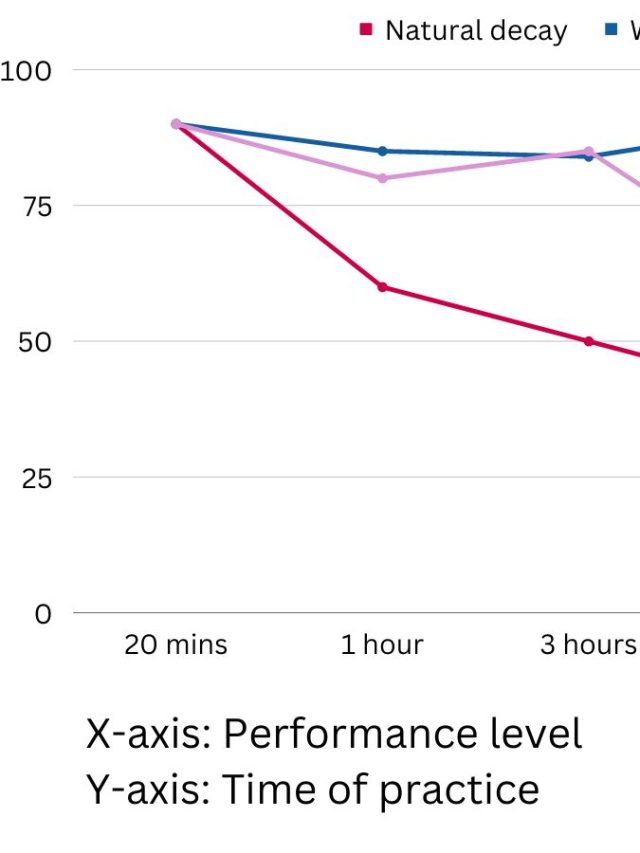

How consumers overcome the framing effect

As a consumer, you are not doomed to fall for the framing effect. Like the previous research shows, mental effort and emotions differentiate different frames. So changing the mental effort and distancing from emotions helps.

Ok, so what can you do as a consumer to remove the framing effect from the product’s messaging and packaging? Research shows that 3 types of mental effort reduce the impact of frames on decision-making.

1. Compare pros & cons

Consumers can counter framing effects by listing the pros and cons of the options[11] presented. For example, if a tablet is presented with a positive frame like “9 out of 10 patients feel no side effects” vs. a negative frame like “ Only 1 out of 10 patients feel side effects,” the first frame might encourage a purchase but the second one might not. That is when the framing effect transforms equal options into unequal options through verbal cues that represent a gain vs. a loss. Using a pros and cons technique to evaluate both options – “pros: 90% good, cons: 10% bad” – can effectively cancel out the framing effect and both options are considered equal. One explanation for this is that the pros and cons method de-biases the framing effect by bringing attention to the actual information in one single “100%” or “whole” and pulling attention away from the individual frame. So information used to evaluate the 2 options is transformed and reconceptualized in one’s working memory, which becomes the new reference to evaluate options.

2. Think like a scientist

In a study[12], researchers saw that instructing participants to “think like a scientist” as opposed to “rely on gut reactions” reduced the impact of framing effects. Framing effect acts as a heuristic – shortcut method – to simplify decisions using emotions and small bits of information. Critical thinking is deliberate and purposeful, so the information from the advertisement is analyzed at a deeper level.

3. Think about the product in your second/third language

The framing effect can vanish[13] when options are presented in a foreign language. A second language generally takes a little more cognitive effort than a first language. A lot more effort for non-fluent second-language speakers. This added layer of cognitive effort pulls attention away from the frame and the brain enters a more abstract, holistic mode of analysis that suppresses the emotions in the advert/packaging. Plus, the mental translation of the product’s features, cost, value, utility, etc., brings out a new context when the language switches. This “distancing” from the product’s original language helps consumers be more rational in their choices.

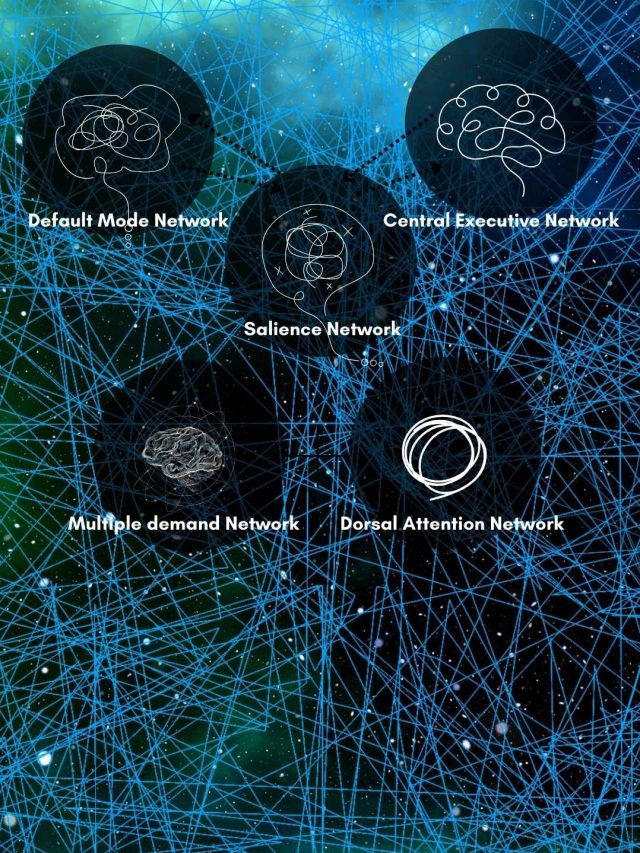

Why does framing work?

All the elements of the frame – the colors, fonts, sounds, imagery, wording, implied meaning, cultural appeal, etc., give additional information to consumers to help them make a decision about a product or pass a good/bad judgment on a product. A fitness influencer with an Instagram profile showing exercises and flexing their body is likely to gain more popularity than a fitness blog which has no indication that the author demonstrates the fitness caliber. The blog is high-risk and does not have visual framing to support the authenticity of fitness advice. The Instagram profile has that “face validity”.

Brain imaging research shows[14] both types of loss – certain loss & uncertain loss – require the same amount of mental effort (as seen by activity in specific brain regions). But, on the contrary, choosing a certain gain requires very little effort compared to an uncertain gain. The fMRI scans in the study show different frames induce different cognitive effort. Their analysis suggests consumers will most likely choose a product that promises them some benefit (certain gain), but if they are taking a risk on a product, they will still take their chances and not attempt to minimize risk. So when a product uses framing to guarantee a benefit, we fall for it easily, and ignore the risks that go unhighlighted.

Emotions, presentation sizes, color palettes, images, idioms, cultural references, etc., can also provide a frame (contextual cues) to important information like health consequences and pricing. Research shows[15] that framing effects emerge from relying on emotion-based thinking, commonly called the intuitive system 1 thinking. Frames affect emotions and those aid decision-making. Since the brain prefers an overall evaluation instead of evaluating each individual bit of information, frames exert a powerful force on decisions by using emotions as the “overall evaluation”. Emotions simplify product evaluations by making the whole product easy to judge.

Frames may also create a reference point in the mind that influences whether a product is a good or bad buy. E.g., if there is a identity frame talking about a vegan lifestyle, someone who doesn’t want that association will reject it.

Takeaway

Framing Effect: Contextual elements like wording, imagery, colors, culture, identity, sounds, numbers, etc., create a strong bias in favor of a product. Critical thinking, pros & cons thinking, and second-language thinking reduce the bias.

Sources

[2]: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11109-008-9056-y.pdf

[3]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/25742442.2022.2087451

[4]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24279933_Crossmodal_transfer_of_emotion_by_music

[5]: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/eeejbrese/v_3a69_3ay_3a2016_3ai_3a3_3ap_3a1022-1027.htm

[6]: https://thesis.topco-global.com/TopcoTRC/2011_Thesis/G0017.pdf

[7]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17538068.2018.1435017

[8]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749597898928047

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749597801929838

[10]: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.7455683

[11]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S073839910700434X

[12]: https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/67B/2/139/537897?login=true

[13]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956797611432178

[14]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222545683_The_framing_effect_and_risky_decisions_Examining_cognitive_functions_with_fMRI

[15]: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2012-02785-001

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.