The average person spends a large portion of waking hours studying in the first 20 years of life. A lot more of skill-learning happens based on the person’s career choice. In essence, you’d be spending 11-18% of your life acquiring information and skills, formally.

If you have ever asked ‘how to study smart?’, this article is for you because it is based on well-researched techniques in cognitive science. This post will teach you how to study efficiently. To stay relaxed before exams or skill demonstrations, follow these tips instead.

We’ll begin with how you can implement each study technique for 3 categories of study material – biology (remembering animal classification), math (solving equations), and literature (learning about the authors).

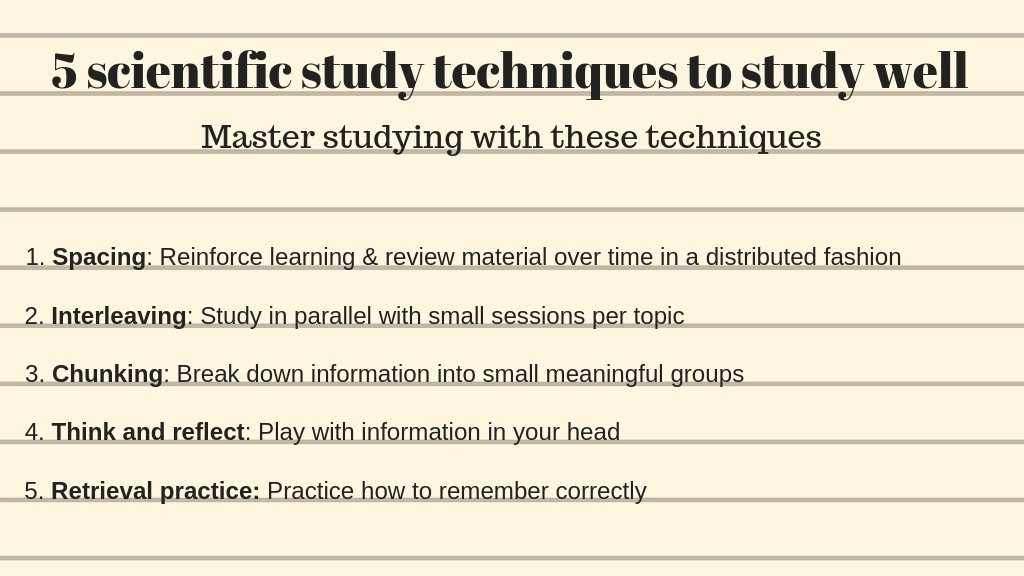

- How to study efficiently: 5 of the best study techniques!

- 1. Spacing – A way to counter forgetting information over time & improve long-term memory

- 2. Interleaving – An effective but counterintuitive technique to learn related content

- 3. Chunking – Grouping information makes it easy for the brain to remember and comprehend

- 4. Thinking and reflecting – Play with information till you develop an intuition

- 5. Retrieval practice – learn how to remember your learning to prove that you have learned

- Study techniques (summary)

- Sources

How to study efficiently: 5 of the best study techniques!

Here is a dense lesson on learning how to learn.

The content in the current post is now condensed into a larger, more diverse article on the best and worst study tips. You may also want to check out 7 bad study habits that dramatically hamper learning. If you cannot develop new study habits, begin by stopping the bad ones.

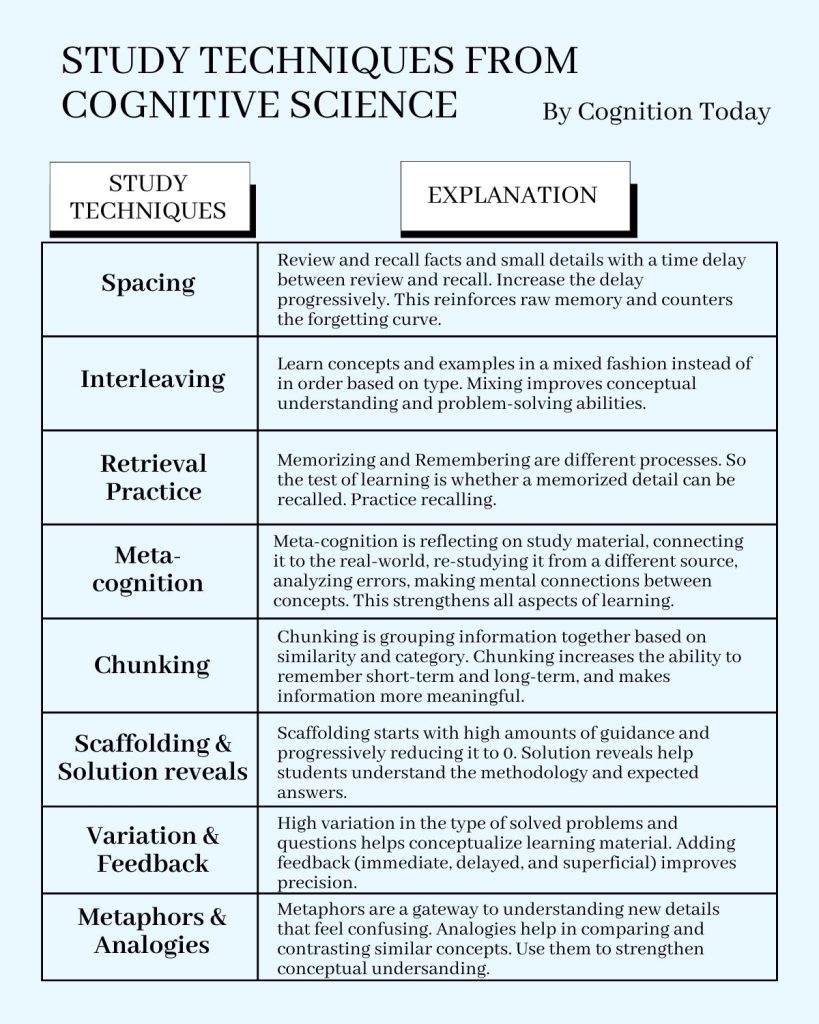

For this post, we’ll focus on structured study strategies. I’ve selected a few for this article, but the visual below is a broader context.

1. Spacing – A way to counter forgetting information over time & improve long-term memory

Information that goes in your head starts decaying immediately. Every now and then, remember to remember the content and repeat it. It is time to hijack the spacing effect – distributed learning sessions of short intervals across a long period of time promote memory. When you ‘space’ away from your study material and then get back to it, you reinforce learning while it is decaying. This makes the decay slower and memory for that learning stronger.

The first time you use spacing and revise your study material, wait for a few minutes and go back to it, then wait for 30 mins, then 1 hour, then 4 hours, then before sleep, then night, then the next day, then in 3 days. Works best with very small but difficult bits of information. So, eventually, the decay of information is so slow that it is insignificant.

A large body of literature[1] shows that spacing promotes long-term learning[2]. Much better than massing, which is a brute-force method of continuously cramming 1 topic for hours at a time.

Inductive thinking is crucial to learning because we often need to understand concepts based on examples from study materials and other resources. Although back-to-back studying (massed revision) creates a sense of quality studying, inductive learning benefits more from spacing[3]. Massing is also much worse at improving conceptual understanding than spacing. Those who learn via spacing have better interpolation and extrapolation[4] skills.

Specifically, the study technique I am referring to is called spaced repetition. To use it correctly, you have to review your material in small bits after increasing intervals of time.

One other related technique is distributed practice. This is a little bit different from spaced repetition in the sense that distributed practice is learning over time without progressively increasing the time interval between sessions. For example, review every 30-40 hours. Plain and simple – distribute your learning over time.

Spaced repetition and distributed practice are two techniques that employ the spacing effect – Short learning sessions (under 30 minutes) spread over a long period of time are better than one single lengthy study session. You can have 4 30-minute learning sessions spread over 4 hours and those will be more effective than 1 single 4-hour long study session. Spacing improves long-term memory[5] and the learning of new concepts[6]. So when in doubt, study in intervals of 30 minutes and take a break after each session.

Examples

Biology: You have to memorize the animal classification system for a few animals. Say 10. First, you spend about 2-4 minutes reviewing all of it. Second, pick your first animal. Review it. Then, repeat the review after 5 minutes, then 15 minutes, then 45 minutes, then 2 hours, then 5 hours, then 12 hours, then the next day. By now, you’ll be thorough with it.

Math: You need to learn how to solve quadratic equations (or other kinds). Let us say you have 3-4 categories of such equations. Use the spacing technique and review it after a few minutes, then 20 minutes, then 45 minutes, then solve a few problems in 3 hours, then in 8 hours. Just 2 new problems each time. Continue spacing and learning for a few days and you’ll have learned your math problems perfectly.

Literature: You have to learn the authors of tonnes of books and then the general backstory. Apply the spacing technique for 1 author. Increase the gaps for revision in this fashion – after 10 minutes, after 20, then after 1 hour, then 3 hours, and so forth until you have gained mastery over your learning.

Sometimes, you can increase the time intervals to something like 1 hour, 5 hours, 12 hours, 4 days, and so forth.

I am not overstating when I say that spaced repetition IS perhaps the best study technique you will ever use.

Say you have 3 topics (A, B, C) planned for the next 5 days. An inefficient yet common study technique is – spending a whole lot of time on 1 topic and then returning to the next topic, and then, the next. Interleaving[7]is, with strong evidence[8], better than that.

Interleaving is learning multiple related concepts in a mixed way. You take your topic A and then spend ‘mini-blocks’ of 20 mins on A, 20 on B, 20 on C. Plan your study as ABC ABC ABC or get creative- ABC, ACB, BCA. All of these should be short ‘interleaved’ sessions, and you should repeat the study pattern over a long period of time. Not in a single stretch. Use this study technique for topics that are related, not disparate. The more related A, B, C are, the better it is. Basically, study in parallel and not in series. This way, learning

Interleaving primarily improves the understanding of similar concepts[10] and helps distinguish them better. And, it is effective in learning math[11]. Go ahead; perhaps by doing well, you might fall in love with mathematics!

Interleaved practice is a newer and better technique that contradicts conventional learning wisdom of focusing only on 1 thing for long (massed learning). This study tip requires a little getting used to but is well worth every minute spent.

Examples

Biology: Learn the 10 animals in pseudo-parallel. That is, review them in succession. Don’t wait for learning to occur for one animal and then move on to the next one. Let the learning for all 10 begin simultaneously and then over time, let them be ‘learned’ simultaneously. You can interleave each time you use spacing.

Math: Solve problems from multiple categories in one small study session (<45 minutes). Interleave and then mix up the sequence of solving different problems. Interleaved practice combined with a large variety of learning tasks can maximize your general intuition for solving math.

Literature: Interleave the author bios in a meaningful way so you can compare and contrast aspects of each author. Remember, the more unrelated the author’s backstories are, the less effective interleaving is. In that case, you can exclusively rely on spacing.

3. Chunking – Grouping information makes it easy for the brain to remember and comprehend

Break down information into meaningful groups, even if they come from different chapters. Chunking is about organizing information into small useful groups[12]. Things that can be grouped together form a small unit. Each unit is a bucketful of information that your brain handles constructively[13]. Scatter the information, your brain will be confused. Be creative in forming categories to chunk. Let there be an imaginary thread that links information inside a chunk.

Cognitive psychologists have studied the effects of chunking on memory for more than half a century. It’s almost conventional wisdom. This is just a simple reminder.

Examples

Biology: You can chunk the animals based on their physical information or their genus or perhaps the similarity in their names.

Math: You can chunk the equations based on your approach – factoring them manually or using a formula to solve them (which you can learn through spacing). Perhaps chunking can’t be used in such a learning task. In that case, chunk other bits of information like similar-looking formulas in geometry.

Literature: Perhaps you might find it useful to chunk authors by their genre, age, sex, or even era. Chunking them by your personal impression of them also works.

—–incoming tangent—–

Mirrors are great. The word mirror mirrors rirrom, kinda. Urban dictionary says rirroms are the hottest Spaniards. They have a great fashion sense, which you would like in your reflection in a mirror.

4. Thinking and reflecting – Play with information till you develop an intuition

Thinking and reflecting is something like a mental joyride with information. Connect with information. Look at the essence. Think about the information in any way you can[14]. By doing this, you are strengthening the memory of what you are learning. However, this is supposed to be done without the formal goal of ‘learning’. Have fun with the information. Perhaps, flirt with it. 8) This internalizes information, taps into your motivation, and creates an intuitive understanding of it. It anchors your learning in what you know better, and that anchoring is critical for memory.

Thinking and reflecting on what you’ve learned is called metacognition. It also develops a related brain process of metamemory, which tells you if you know something without remembering it. It is the source of confidence in your memory.

Examples

All topics: Spend time thinking about the information in creative ways. See if you can attach any real-life experience related to that information. Try to use imagination and mental imagery. How would it be if you are the Animal or the Author? Be in the information’s shoes and think. Be creative. Try things out.

5. Retrieval practice – learn how to remember your learning to prove that you have learned

Simply studying does not guarantee ‘remembering’. Remembering is a skill and retrieval practice is ‘practicing to remember’. So once you finish studying your ‘chunks’, do some retrieval practice over it. Confirm that you can correctly remember it and make a mental note of it. Just acknowledge it.

Practicing retrieval makes learning meaningful[15]. You can do some retrieval practice using quizzes and tests[16] too. Using a mixture of spacing and retrieval practice[17], you can distribute your retrieval practice over time and maximize the benefits from both study techniques. Tonnes of new[18] research shows the benefits of retrieval practice.

However, performance pressure could disrupt the benefits of retrieval practice[19]. Have confidence in your retrieval practice and don’t let performance pressure get the better of you. Remember that you are already verifying your learning using this study technique.

Practicing to remember improves another very important learning process called “prospective memory”. Prospective memory is known as remembering to remember. This process is important for studying because you often must remind yourself to do a future task while learning. For example, you may have to verify facts or extend understanding or add some details to your notes or review a related concept that you vaguely remembered while studying a different topic.

Examples

Biology: Practice remembering your content. Go through your mind and try to pull out the information. Each time there is some difficulty, review and repeat mentally (or orally)

Math: You don’t need much memory to remember how to solve problems. You can leave the retrieval practice for the formulas and geometric diagrams.

Literature: Retrieval practice is exceptionally useful for authors and their backgrounds. After some practice, you’ll just know about the authors.

…

…..

…..

…..

…..

……….

(Now, the greatest, the oldest, the wisest advice on how to study well)

……………

… sleep well[20] and sleep enough[21]!

In case you need to learn how to take good notes and learn from video content, I’ve prepared a guide for that too.

Bonus Learning/Study tip 1: Confidence makes the learning output better

Usually, confidence plays a very significant role. It is important to note that after going through these study practices, you feel confident that you really have put in the work for good learning. This won’t be hard because you would be testing yourself and confirming that you have learned your material with retrieval practice.

With a calm and composed mind, you are good to go!

Bonus Learning/Study tip 2: Spend time and get it right first

For something like math or science problems, it is important for you to spend time and get it right a few times so you have enough time after the first tiny bit of learning to review using these techniques. It is OK if you take 1 hour to solve a single problem. That time is not lost, using these techniques, you can easily speed up the review because you spent 1 hour of dedicated solving. Your brain will then be very conducive to learning newer, related material.

Bonus Learning/Study tip 3: Teach others

Speak about your learning and tell your friends about it. Perhaps you can teach and bolster your learning. By doing this social verification of learning, you further ground the information in your head. I personally tell my friends about interesting things I learn. That sometimes leads to conversations that help me further my learning and highlight my confusion.

Bonus Learning/Study tip 4: Have fun, engage your senses, be curious, and relate to it

Having fun is extremely important if you want to optimize your learning potential because it avails extra cognitive resources, enables toggling between 2 neural modes for broad and narrow attention, and associates information with reward. But, that isn’t the focus of this article. You can read about having fun and learning here.

We have now finished looking at the tasty juicy meat of this article.

Am I making you hungry? Here is something to learn about Food Psychology!

You may feel that is a lot to do but I can assure you that using these techniques will significantly reward you with free time to enjoy! I recommend using all of these study techniques and study tips whenever possible.

This is not an exhaustive list. There are many aspects of learning and studying such as sleep, feedback, diet, variety, motivation, etc. that I have not covered here. In the future, I’ll cover many more topics on learning efficiently. If you want more right now, you can check these out:

- How to learn numbers effectively

- How to learn new words effectively

- Why you should learn new things even if you don’t need them

- How to boost memory effectively

- How to learn anything new effectively

- How to improve your memory for facts

- Daily habits to improve confidence in memory

- Should you listen to music while studying?

- How to reduce test anxiety during a test

Study techniques (summary)

- Use spacing so information is reinforced to last longer. Prevent the information from early decay.

- Interleaving would help you learn a variety of things effectively. It is better than studying a single topic for a large duration. Study in parallel.

- Spacing & interleaving is better than massed learning. Many 30-minute intervals in a day or week are better than a few long stretches.

- Chunk so that the brain consolidates meaningful groups of information.

- Think and reflect so the information has added value to you and your brain.

- Do some retrieval practice so you know that you can remember effectively. Spacing and retrieval practice combines well. So does interleaving and spacing.

- Be confident about your learning.

- Put deliberate effort into getting things right at least a few times.

- Teach others.

- Concentrating on studies is not as important as concentrating correctly during small study sessions.

- Use many of these study tips together. They complement each other.

Trust me; you master these practical & efficient study techniques and you will be equipped to ace exams and actually learn.

Special mention: Some of these techniques are also discussed in the Coursera course called Learning How To Learn[22]. It is one of the best MOOCs and I highly recommend it.

P.S. I love VSauce.

P.P.S. ICYMI, I love VSauce[23].

P.P.P.S. Need consultation on how to implement these study techniques & learn? Leave a comment or write to me here[24].

Sources

[2]: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2372732215624708

[3]: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02127.x

[4]: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0032184

[5]: http://learnmem.cshlp.org/content/14/5/368.short

[6]: https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01781.x

[7]: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-interleaving-effect-mixing-it-up-boosts-learning/

[8]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319170627_How_Should_Exemplars_Be_Sequenced_in_Inductive_Learning_Empirical_Evidence_Versus_Learners%27_Opinions

[9]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319280546_Interleaved_Presentation_Benefits_Science_Category_Learning

[10]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10648-012-9201-3

[11]: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-44133-001

[12]: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661300016624

[13]: http://www.chrest.info/fg/papers/Chunking-TICS.pdf

[14]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035598/

[15]: http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2016/06/learning-memory.aspx

[16]: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sjop.12093/full

[17]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271389338_Retrieval_Practice_and_Spacing_Effects_in_Young_and_Older_Adults_An_Examination_of_the_Benefits_of_Desirable_Difficulty

[18]: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1002/ase.1668/full

[19]: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acp.3032/full

[20]: http://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/healthy/matters/benefits-of-sleep/learning-memory

[21]: http://www.pnas.org/content/104/18/7723.short

[22]: https://www.coursera.org/learn/learning-how-to-learn

[23]: https://www.youtube.com/user/Vsauce

[24]: mailto:adityashukla77@gmail.com

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.

Very good information bro

Keep it up.

Thank you, Rahul!:)

Would love your feedback on this… it’s a spaced repetition project I’m working on.

https://getpolarized.io/

I want to information daily

Do you want to learn new information daily?