Annie gets mad and breaks a pen in front of her friends. No one feels bad for the pen. Alyssa breaks a pen she lovingly calls Gerald. Everyone feels bad for Gerald because he died.

There are no secrets to anthropomorphizing a product – making it feel human with human qualities. At the very least, you slap a name on it, give it a face, and half the work is done. But that is so common that product designers and CXOs must imagine more – far more. Give it actual human qualities.

Def: Anthropomorphizing (anthro-po-morph-ising) – ascribing human-like status to something non-human because it has qualities that mimic human behavior. It is a human process and non-human things like products and brands have qualities that make it easy to anthropomorphize them in our heads. Technically, anything – even a stone, a rug, a key – can be anthropomorphized by a person regardless of its qualities; it’s just that human-mimicking qualities make it easier.

This is a long article, but since the pay-off is more potential money and brand-level benefits, go through the theory and practical insights.

Human qualities now are, quite literally, in the eye of the beholder, too. Humanized products or anthropomorphized products always have 2 sides. Qualities that belong to the product/brand and qualities humans can make sense of.

Brand’s POV: Qualities that belong to the product/brand

- Has a name, face, personality, form/body

- Does something for you, ask for things in return (like engaging with another human)

Consumer’s POV: Qualities we perceive

- Evokes empathy and emotional attachment

- We ascribe motivation and intention to it as if it has a story to tell

- Looks and feels familiar

Should you anthropomorphize?

Anthropomorphism is commonly used as a marketing tool called anthropomorphic marketing[1], which is quite popular in packaging food[2], designing chatbots and AI assistants, and electronics.

Should you humanize your product? The answer seems yes, but not necessarily. Look at a pencil; it doesn’t need humanness, even if we CAN ascribe humanness to it. Generally, these are the trends:

- Anthropomorphized products are likely to sell more (reasons below).

- Humanized brands have more brand loyalty, and they enter a relationship with a consumer[3] like humans and humans connect socially and intimately.

- Anthropomorphized products induce happiness[4], similar to how experiences like movies create happiness.

- Anthropomorphism increases user engagement rate, particularly for tech.[5]

- People love anthropomorphized products more. A study suggests[6] brand love increases via (potentially) an increase in product familiarity and ease of understanding it, products becoming a part of the user’s identity, products feeling similar in “vibe” to consumers

- People are willing to pay more for humanized products. A study[7] estimates an increase of 7% by visually anthropomorphizing it.

- People get more emotionally attached to humanized hospitality brands[8].

- Anthromoprohism makes technology a “social companion[9].”

It’s not just these benefits, like the food case we will see ahead, humanizing can save subpar products. Most products can be classified as humanized vs. objectified[10]. Objectified products are feature-centric, and the consumers pay attention to the specs and features. Humanized products grab attention via emotion and not specs/features. If a product is outclassed by competition, anthropomorphizing can give it an edge by distracting the consumer from the features and making them attached to the humanized aspects. So, more brand love and loyalty without being the best in class, assuming the product is at the right price point.

In some cases, anthropomorphism creates problems. In one study[11], researchers found that gamers felt less in control and had lower gaming enjoyment when their in-game helper assistant was anthropomorphized. This effect is seen in the industry, too. In many of the popular complex games like DotA 2, the guide and in-game helper assistant is not humanized. It just makes numerical and decision suggestions where the player feels in complete control.

Why do we anthropomorphize?

Think of it this way – the best way to parse the world around us is through our experience as a “human,” so all our evaluations have that Human reference point. When the behavior of a product or brand matches a human’s, we anthropomorphize.

We see cars with grilles and headlights appearing as faces because our brains ARE inclined to see human patterns everywhere, especially faces (it’s called pareidolia[12]). We impose humanness on ambiguous and neutral patterns.

Alexa has a voice and personality. Siri has a voice and personality. They allow us to interact as if they are human in some capacity but not human enough to accept their limitations.

Similar to seeing faces, we have a “theory of mind[13]” brain network, often called the “mirror neuron” network that allows us to ascribe motivation and intention to others. It allows us to acknowledge that others have a mind of their own and will behave according to that mind. That’s our current understanding of the source of empathy. Now, a concept related to empathy, rather a precursor to empathy, is the idea of mentalizing – our tendency to think something has a mind of its own. Your customer can mentalize a product and think – “this device can think and do complex things without me telling it to; it’s so smart!” Mentalizing a product/brand is a direct way to say it is humanized.

Like “empathy” becoming a bias to humanize something, a cuteness bias exists too. We tend to ascribe more human qualities to anything that looks cute, and dehumanize things that are disgusting.[14] Most notably, pets and cute avatar helper assistants in apps. Why cute? Cute = humanized comes from the baby schema. It’s a mental “filter” that processes information as if the object/brand is a helpless, innocent baby who wants to capture attention and needs you. The baby’s form-factor like size and roundness, the baby’s personality traits such as innocence and exploring, and the baby’s social demands of us giving it care. All of them create the baby schema. When the baby schema is triggered by cues that resemble a baby, we think it is cute, and when we think it is cute, we think it is more human than something that isn’t cute. Similarly, if something evokes disgust, say from a “rotting carcass” schema, we think it is less human.

Finally, it’s the emotions that drive our relationship with machines and how much we humanize them[15]. If a laptop is heating up and the fan spins faster to cool it, do we say the laptop is stressed and angry? Humans have emotions at a basic biological level. But the form they take can have parallels in machines. The mental state of an emotion can happen in a machine state based on the variation in its behavior, how it functions, how it responds to us. Can we say an app is “annoying”? I think so. Imagine an app where you have to select yes or no. When you press yes, it throws out colors on the screen as if it is celebrating. But if you say select no, it moves the button elsewhere. It does this 5 times before accepting a no. This is very much like an annoying human.

All a product has to do is have qualities that feel like emotions, good and bad. So, it needs features/attributes that parallel a few dimensions of human emotion.

- Positive or negative – Does the product have a correct and incorrect way to use? That’s the basic. A hairdryer will show positive behavior if you dry hair with it. You’ll love it if you use it correctly. But if you use it to dry clothes, you’ll hate it for negative behavior (even though it was your fault). Similarly, if the accidental touch protection locks you out of your phone for 20 minutes, you’ll probably get frustrated and think the product is behaving negatively toward you.

- Intensity – Does the product have an intensity that changes? Most products that have a “settings” option have an intensity. A razor blade setting ranging from low sharpness to high sharpness.

- Variation – Do the product’s responses change? Does it act tired or efficient? All our electronics have a tired-ness setting – low battery and overheating. Does it act clumsy and broken? Our phones do when the storage is full, or the RAM is fully occupied.

- Mood – Does the product have a consistent, long-term way of responding to you? Is it calm and helpful? Is it sassy and snarky? Is it going to mock you or hold your hand? A mood is like a long-lasting, stable set of emotions. Regarding a product or brand, it’s a stable way of responding to you through communication, apps, tutorials, ads, after-sales chatbots, etc.

We project human-ness onto the product because we can. Look at this finding[16] – we tend to sell used products for higher prices because we have anthropomorphized them. The inflation comes from a positive value toward past use which typically involves an emotional connection with the product.

A deeper look at what it means to give something human qualities

Researchers Epley, Nicholas Waytz, Adam Cacioppo, John T.[17] have defined 3 conditions under which we are likely to anthropomorphize. The 3 are Sociality motivation, Effectance motivation, and Elicited agent Knowledge, popularly called the SEEK model.

It has knowledge (elicited agent knowledge): We humanize things that feel like they can apply human knowledge in ways we can relate to and find useful. A chatbot is most humanizable if it has affectations and uses words and idioms/metaphors the way humans use them. When a non-human entity, like a chatbot, exhibits behaviors that align with our understanding of human behavior, we’re more likely to attribute human-like qualities to it. This goes beyond language. Other human behaviors like wanting to rest and take time off, acting irrationally or unexpectedly, etc., can make it more human. You may have noticed that if a product fails to do what it is supposed to do, we get angry. That’s because now it is humanized and we want it to “behave”.

It has motivations (effectance motivation): We humanize things that want to understand us and other things. Especially when they try to explain and solve problems. Effectance motivation means the product has a causal effect on its environment, which includes us. An analytics interface can be humanized if it extracts meaning from data and tells us a story of how that data makes sense. When a non-human entity appears to explore the world, show curiosity, and understand the world around it, it aligns with a very core human trait of “sense-making,” which makes the entity very human-like. In a sense, a human anthropomorphizes any entity if it mimics motivations and intentions in ways we understand. For example, a server network optimizing its routing doesn’t feel humanized in technical terms, but it can feel human-like if the server’s log report says “finding the fastest route to serve you the website”.

It understands, promotes, and needs socializing (sociality motivation): We humanize things that appear to want to socialize and connect with others. A brand that wants to just talk with its customers and share stories feels more human. Non-human entities that display behaviors that suggest social interaction or emotional connection (even if it is just wording), such as a brand engaging in direct communication with customers, are more likely to be anthropomorphized. It’s not just a desire to connect that makes an entity more human. It has to show human behavior that is social – the good, the bad, and the delulu. If Amazon Alexa says it has a crush on Siri, it gets even more human. If an app says it needs some love and attention from you, it’s even more human than before. In fact, if the product prompts you to socialize in a way that shows concern for your well-being as a user, it is now actively humanized.

The easiest way to bind all of these together is in the form of a story. If a product/brand has a story behind it, which it (or marketers) can tell, it is humanized.

What this means for brands

If we look at these 3 factors and try to come up with tangible things that anthropomorphize brands, we get the following qualities:

- The brand receives our trust, like a human would. The brand also “earns” trust, like a human should.

- The brand and product has a story, like every human does.

- The brand speaks of things that you relate to in words you understand about things you require/need, just like an empathetic human.

- The brand has knowledge that a more skilled or informed human would provide you.

- The brand has human idiosyncrasies that make it human – voice affectations, micro-expressions, style and fashion, mimics emotions, etc.

- The product undergoes change like a human does. It adapts, it improves, it makes mistakes, it tries things out.

- The brand evokes familiarity in humans through its look and feel and/or words.

- The consumer and the brand/product form an emotional connection.

Boundaries of humanizing

So, having knowledge, motivation, and social components are the minimum requirements for a brand/product to get humanized. But they don’t form the whole picture because humans have visual precedence and cultural nuances that determine the success of the 3 factors.

- Look and feel: Visual precedence means – looks matter a lot, looks matter first, and looks bias later perceptions with a few milliseconds. Without visuals, humanizing is hard because our brain just look for visual details as a way to process everything. Look at ChatGPT, excellent human-like language, but it lacks a relatable visual form, so researchers are studying it[18] not from an anthropomorphism point of view but from a “perceived humanness” point of view based on ChatGPT’s use of language.

- Cultural nuances: Anthropomorphism is literally a human-centric set of qualities applied to non-human entities. And because we are cultural beings, culture makes things human. The first level of culture in humanizing is cultural congruence. If the culture shown by a brand is relatable to humans in that demographic, it is more humanized than bringing a culture that isn’t relatable. A humanized product in India that enjoys Diwali and Dussera may not be humanized in the US, but a US product that talks of loving Thanksgiving would be. Studies suggest[19] collectivistic cultures, like those found in Asian countries, prefer anthropomorphized products (most categories) more than individualistic cultures like those found in Europe and the Americas.

Food: The exception

People often love humanized food – cookies with smileys, cereals with mascots, nutrition supplements with “power” humans, etc. But when it comes to meats, people prefer meat that doesn’t look like the animal it came[20] from because it induces negative feelings such as guilt. This is similar to the uncanny valley situation I’ve described below. Another exception, contrary to popular belief, is that children are averse to humanized food. This is mainly due to their “theory of mind” development, which starts at around 5 years of age. The ToM development gives empathy and metaphors, so children tend to avoid humanized food because it “feels” like they are hurting something alive.

Food brands have it tricky.[21] It’s not as simple as humanizing electronics. But one tested situation is reducing ugly food produce wastage. People all over the world prefer fruits and vegetables that look pretty – they are polished, symmetrical, have bright colors, they are well-shaped, etc. So ugly food gets rejected or thrown away as food waste. Anthropomorphising the ugly food can help reduce wastage and possibly sales, too. One simple trick can work – place a photo of a farmer on the container with ugly food; it gets humanized and thus sells more.

When anthropomorphism gets weird

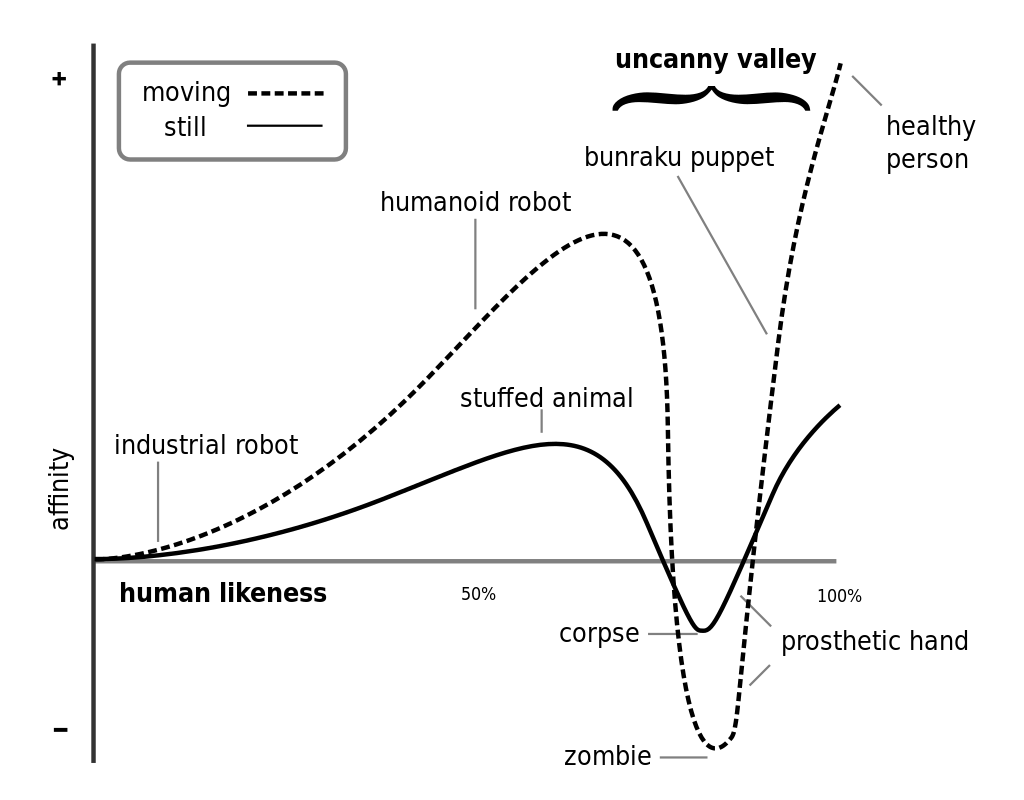

You’ve heard of the uncanny valley, probably. It’s a graph describing how we feel about a robot that looks humanlike from not-human to full-blown human replicas with soft toys and artificial limbs in between.

This graph has a lot to unpack, so let’s walk through the valley.

The X axis is the “level of anthropomorphism” or “human-like” for robots. The Y axis is our emotional response to it (ranging from positive to negative. The dotted line is the robot or thing while moving. The continuous line represents a still image or non-moving instance of the robot.

Obviously, a healthy, moving person is most human-like and gets the most “likability” from other humans. An industrial robot, which might look like a random machine, has the least amount of human traits and we have the most neutral emotional response to it.

But, somewhere in between the graph goes jiggly. As the robot gets more “terminator-like” without the outer human shell, we like it and find it cool. It is moderately anthropomorphic and we have some level of positive emotional reactions toward it. The Uncanny Valley starts here.

Suddenly, after a humanoid robot like Baymax or Optimus Prime, we start having strong negative reactions to a robot or thing. Like the “almost human” robots with artificial faces we see being unveiled at tech shows. That slightly odd lip movement and the lack of microexpressions give most people the creeps. So the level of anthropomorphism is very high – almost human-like – and yet our reaction is negative. It’s theorized that the negative reaction is as negative as seeing a zombie.

We’ve not yet found robots that become so human-like that they have crossed the valley. Maybe Jia Jia does. But we do have robots that look less human-like with enough human-like qualities for us to find them cute, like the Boston Dynamics’ robots.

So, as human-ness increases in an object (robot, doll, alien) we start having positive reactions to it with empathy, until it becomes very human-like where we get repelled by it, until it becomes even more human-like and we start evoking empathy for it again.

The bottom line: If you want to humanize a product or brand, avoid the uncanny valley unless you are at the forefront of technology that pushes boundaries.

How should you anthropomorphize a product/brand?

Here’s a checklist, the very basics.

- It has a name, face, and form

- It shows a pattern of behavior (we call it personality)

- It interacts with you (we call it communication)

- It suggests and recommends things that you find useful (we call it empathy)

- It shows minor inconsistencies (to err is human)

- It isn’t so human-like in a realistic way that it stops being cute and becomes creepy/repulsive

- It evolves and changes, just like people do (it has adaptability)

The future

We’ve learned how to anthropomorphize products and brands through graphics, digital presence, and design. But, one future direction is AI-powered products that sell themselves. Imagine a product that sells itself, describes itself, recommends how to use it, etc. Researchers considered this scenario with a camera, laptop, and TV.[22] They concluded people are willing to pay more – up to 20% more – for products that sell themselves as if they are their own humanized versions talking about themselves.

Sources

[2]: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EJM-12-2012-0692/full/html

[3]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1057740816301061

[4]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11002-021-09564-w

[5]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311975.2023.2249897?src=recsys

[6]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/bm.2014.14

[7]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07421222.2019.1598691

[8]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02642069.2021.2012163?src=recsys

[9]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08944393211065867

[10]: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/254191/1/1739001109.pdf

[11]: https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/43/2/282/2572275

[12]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1017/prp.2019.27

[13]: https://direct.mit.edu/jocn/article-abstract/19/8/1354/4416/Mirror-Neuron-and-Theory-of-Mind-Mechanisms

[14]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1754073911402396

[15]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12369-014-0263-x

[16]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148296320308766

[17]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-13558-002

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0160791X23001677

[19]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167811623000411

[20]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666323024972

[21]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0969698921001223

[22]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167923623001768

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.