Forming new habits can be difficult but ultimately necessary to live easily. Habits are stable patterns of behavior or thought that happen automatically without needing much decision-making. Whether a new habit is reading, journaling, or daily cleaning, it needs time, repetition, and a commitment to continue. Building good habits, along with emotional regulation, is a way to self-regulate[1] and adapt.

- What are habits?

- The basics of forming any habit

- Fast facts: Characteristics of a habit

- Structure of a habit

- What happens in the mind during a habit?

-

How to form new habits easily

- 1. Describe the habit clearly

- 2. Connect the new habit to an old habit

- 3. Make the habit as easy as possible

- 4. Declare rewards for your habit

- 5. Make your habit a part of your identity

- 6. Don’t think, just repeat it

- 7. Push interfering habits aside with alternatives

- 8. Make small changes at a time

- 9. Make the environment encouraging

- 10. Ask someone or some app to remind you

- 11. Stay accountable to yourself and others

- 12. Gamify your habit

- Bonus: How to kill a nervous habit

- How to break old sticky habits

- How long does it take to form a habit?

- Sources

What are habits?

A habit is a goal-directed behavior[2] that has become automatic through repetition and requires minimal attention. Repetition increases the efficiency of behavior and near-automatic stimuli-response mechanisms like habits conserve biological and cognitive energy. Habits help improve productivity with minimal effort. The opposite of a habit is a novel and purposeful goal-directed behavior. Mindfulness is another behavior different from habits (which some call mindless behavior), but it can also turn into a habit through practice. Unlike habits (e.g., scrolling Instagram), goal-directed behavior or mindful behavior is planned and requires continuous attention (e.g., following a cooking recipe). Both types of behavior – automatic habits and purposeful goal-directed behavior help select a behavioral response in any context[3].

The simplest way to evaluate a habit is across 3 dimensions:

- Frequency: How often does it occur?

- Strength: How strong or robust is it?

- Function: Is it useful, harmful, or neutral?

The basics of forming any habit

Habits are formed after repeating a response to a stimulus to get a reward. With that in mind,

- Repeat a response/behavior. If it’s a daily habit, do it every day in a similar context. If it is a weekly routine, don’t skip any week.

- Be clear about how you perform your routine/response. Ensure you can visualize the habit.

- Have a clear start and end to your habit.

- Free-up time to accommodate your habit.

- Be in an environment conducive to habit formation (with little interference, no/little demand to perform conflicting actions, or where new behaviors are not punished but rewarded).

Fast facts: Characteristics of a habit

- Habits are learned and acquired, not innate. E.g., Blood circulation isn’t, brushing is.

- Habits are automatic and almost involuntary, or as some like to say, unconscious or subconscious. E.g, Checking notifications and scrolling without knowing how you got there.

- Habits are the most stable and predictable forms of behavior apart from biological reflexes. Novel or unrehearsed performances are the least predictable.

- Habits conserve energy by being biologically efficient. They produce minimal cognitive load.

- Habits start with a cue, have a routine, and provide a reward. E.g., Hearing a notification beep (cue), opening the app (routine), consuming media or seeing likes (reward).

- Habits require little to no attention once the habit has formed. E.g., Easily talking with people in the car while driving on a familiar route.

- Habits are repeated in approximately similar contexts. E.g., Smoking urges increase in social drinking contexts.

- Habits have an approximate frequency per day or month. E.g., Drinking coffee every evening.

- Habits have an intensity or strength which describes how flexible, avoidable, or changeable a habit is. High-strength habits are rigid and low-strength habits are easy to suppress.

- Habitual responses are a part of being an expert at something, although not always useful.

Structure of a habit

Charles Duhigg’s highly influential book The Power of Habit[4] describes Habits as a 3-step process: The cue, The routine, The reward. Other researchers have used this framework to develop good writing[5], safety, and health habits.

- The Cue is the trigger to your habit. For example, picking up the phone is a cue for opening Instagram. Or, talking about a person can also be a cue to pick up the phone and open Instagram. Cues are environmental, cognitive, or behavioral starting points. These are also commonly known as triggers that initiate a “need” to perform a routine.

- The Routine is the action of your habit. For example, picking up a cigarette, holding it, and lighting it in your mouth. The action or the set of actions needed to perform the habit become automatic when they are repeated. Routines are also commonly called rituals.

- The Reward is the biological and psychological gratification from performing the habit. It is the satiation of a craving processed by the mesocorticolimbic glutametergic pathway [6]of neurons in the brain. This system plays a crucial role in how the brain acts on perceived rewards.

Habits can be used to make students life-long creators[7]. One way to achieve that is by giving them an environment that fosters (cue – reminders, prompts, access to tools) repeated behaviors that lead to knowledge creation (routine – creative work, ideation, collaboration) which in turn satisfies their need to create and grow (reward – satisfaction, accomplishment).

The routines are the main observable “form” of a habit. These routines can be simple repetitions like flossing, practicing sequences like leg-day or arm-day workouts, and strategic rehearsals like studying.

Habits can be modified by changing the cue, routine, or reward. The brain accommodates these changes and the associated habit may decrease or increase in frequency and strength. For example, a habit like smoking can drop in intensity and frequency if its satisfaction (reward) is replaced by a persistent cough (punishment).

What happens in the mind during a habit?

Autopilot mode saves effort: Habits occur at an automatic level and the neural circuits that guide the habit fire in a consistent pattern. This pattern of firing reduces mental effort to start and continue actions[8] that are rewarding. Once started, habits usually run their whole structure. The cue of a habit initiates the entire routine of the habit, where the cue is like the on/off switch and the routine is an electrical transmission to light a bulb. The reward is the light. Once the signal for the habit starts, the rest of the habit starts simultaneously as a pattern of behavior and a pattern of neural firing.

Reduced attention: Most new activities require a lot of mental effort. Particularly, they require executive functioning – paying attention and making decisions. As a habit repeats long enough, one tends to become proficient at it and not require much executive functioning[9]. This means multi-tasking is possible while performing habits because mental space and attention is freed-up for other tasks.

The Mind wanders: As a result of reduced attention, and a reliable “routine,” the mind wanders. Most commonly seen as random thoughts about planning, past events, to-do tasks, musical earworms, etc., appearing as if from nowhere.

Increased importance to intention: Considering habits are repetitive behaviors, we rationalize the importance of our habitual actions through a process called sense-making. We irrationally conclude that habits are intentional because we do them often. We create a narrative that justifies the habit – “I do this because…..” However, they are repeated almost without decision-making regardless of intent or importance. Anything frequent[10] is considered more important than infrequent things, so habitual actions are considered more important just because of their higher frequency.

High emotional arousal: When people are emotional, stressed, or anxious, they rely more on habits. This pattern of behavior is also observed in animals and may explain why negative emotions trigger the use of cognitive biases, heuristics, and automatic minimal-effort behaviors. Research suggests[11] the dorsolateral striatum governs habit-related memories that activate behavior according to the amygdala’s activity which correlates with emotional arousal.

Emotional conclusions: At the end of a habit, a reward encourages the repetition of that habit. These rewards, also called reinforcements, have an emotional effect on the person. They lead to satisfaction, need-fulfillment, gratification, calmness, high energy, etc. These emotional consequences to the response (routine) generated by the stimuli (cue) are maintained through many mechanisms. Typically, operant conditioning – the addition of a reward or the removal of an unpleasant feeling – motivates or changes the frequency of behavior.

How to form new habits easily

- Describe the habit clearly

- Connect the new habit to an old habit

- Make the habit as easy as possible

- Declare rewards for your habit

- Make your habit a part of your identity

- Don’t think, just repeat it

- Push interfering habits aside with alternatives

- Make small changes at a time

- Make the environment encouraging

- Ask someone or some app to remind you

- Stay accountable to yourself and others

- Gamify your habit

1. Describe the habit clearly

It’s important to know what your desired new habit looks and feels like. Ensure you can visualize the habit as realistically as possible.

If you want to walk every day after dinner, ensure you plan and verify the time, place, clothes, route, music, etc., so you can successfully walk.

2. Connect the new habit to an old habit

New habits are easier to form when they start at the end of an existing habit. This is your trigger to kick-start a new routine.

If you want to start reading, do it while having coffee or after your skin-care routine.

3. Make the habit as easy as possible

Easy access to the tools and requirements for performing a habit can help increase the behavior. If the new habit is complex, it’ll be hard to start or successfully repeat enough times for it to become “automatic”.

If you want to start drinking 4 liters of water every day, always keep a full 1-liter bottle with you. Set alarms for water. Keep an extra bottle near your bed or desk.

4. Declare rewards for your habit

Your habits should give some form of intrinsic reward (the value of the habit like health, learning, peace, happiness, achievement) and/or extrinsic reward (money, IG likes, compliments, recognition).

If you want to start writing blogs, start making small posts on IG, FB, LinkedIn, medium, etc., for both types of rewards.

5. Make your habit a part of your identity

Staying consistent in your identity is a powerful instinct. Habits described as a part of identity are easy to repeat. Some habits exist because they uphold an identity – like “I don’t socialize because I am an introvert.” This belief that motivates the habit of avoiding social interactions may be a problem because it can make you feel lonely or socially awkward. The habit can change if you define a new identity and choose behaviors that uphold it. For example, “I’m an introvert but I have social skills to make friends.”

If you want to cycle or swim every day, say you are a hobby cyclist or a swimming enthusiast. Share this identity with others so you are motivated to uphold it.

6. Don’t think, just repeat it

Focus on repeating a habit long enough to not require justifications. Repetition makes it easier to do it the next time. Rationalizing a habit means making decisions that create the opportunity to not start a habit. Eliminate that problem by just “doing” it.

If you want to start an exercise routine, don’t debate the habit in your mind. Trust the routine and follow it as instructed a few times. Then observe the results.

7. Push interfering habits aside with alternatives

An old habit can disrupt any new habit. To make new routines easy, start them at a time you don’t have any interfering habit.

If you want to start a digital detox before sleep, don’t start Netflix before bedtime. Start reading.

8. Make small changes at a time

New habits require changes to existing routines. Small changes[12] at a time can make learning new behaviors easy. Increasing the difficulty or the complexity of a routine in small increments which feel “just achievable[13]” can sustain motivation for longer. More on how to stay motivated.

If you want to start studying for an important exam a year later, get into the habit of studying every day one step at a time with a few short sessions a day at the start of the first month to full-blown revision for a few hours toward the end of the study period.

9. Make the environment encouraging

It is easier to change habits when the environment changes. This is mainly because most cues occur in a particular environment. An abundance of cues creates many opportunities to acquire new habits and also remove triggers for old behavioral patterns.

If you want to build a habit of small-talk, enter an environment where people are friendly. This would help you to have multiple tries and watch others respond to those cues so you can acquire the practical ways to perform the habit – like what to say, how to manage body language, etc.

10. Ask someone or some app to remind you

Getting a text[14] or a reminder from an app or person can help build new habits. The reminder can contain direct reminders or general contextually relevant reminders about the habit in special circumstances.

If you want to build a habit of drinking water, you can set direct reminders like “drink water” or ask someone to occasionally send relevant information like keeping water handy while traveling.

11. Stay accountable to yourself and others

We tend to make decisions that are easy to justify to someone else[15]. So the decision to perform your bad habit routine can change if you have to justify it to someone and they don’t accept the justification. Having a “healthy habit buddy[16]” to acquire the habit with you (like working out) can be quite effective. Romantic partners are just as effective as friends. In some cases, you can stay accountable to a coach or a boss/mentor by showing proof of doing a habit.

If you want to start a new habit like daily jogging or kill an old one like binging 5 hours on Netflix, have a friend or partner do it with you. Let a partner join you for a jog and be mutually supportive. You can also have a partner limit your Netflix routine by watching 2 episodes with you and then plan to watch the rest together on some other day (a watch party could work too). You can also have a mentor/coach remind you about the benefits of a habit and give feedback after you send photos or screenshots of doing a habit.

12. Gamify your habit

Making your habit formation effort feel like a game[17] with classic game features like milestones, playfulness, rewards, and progress tracking can be a good way to speed-up habit learning. For example, place a white chart on a wall and make a dot anywhere with a black pen every time you complete a good habit. Make a red dot when you fail or miss your opportunity. Try to make the black color overpower the red. Try setting up milestones and goals and color over any red dot when you reach that milestone.

Suppose you are on a weight-loss routine – diet, gym, running, etc. – with clearly defined milestones like “6 healthy meals in a row” or “lose 2 inches at the waist.” If you eat an unhealthy meal, you have to add a red dot if it isn’t your cheat day, but you can color it black if you reach a milestone. Strive to make the entire chart black. And if you fail, consider reaching a milestone as gaining a new life because you get to re-do the red dot with a black dot.

Bonus: How to kill a nervous habit

Nervous habits are routines like nail-biting, leg-shaking, and hair-scratching. Research suggests[18] that these habits can be extinguished quickly, possibly in a day, by reverse-tracing the habit repeatedly. By reversing the physical motion of the habit, 12 therapy clients reported in the study lost their habit. Giving clients social approval for attempting to stop the habit helped reduce the habit’s strength. The reverse-tracing involved mindful awareness of their habit routines and how they reverse them.

How to break old sticky habits

- Remove yourself from the cue: Find ways to go away from cues and triggers, so it’s easy to suppress an urge. E.g., If you want to give up bedtime scrolling, keep your phone on silent, so notifications don’t cue you. You can even delete apps to help you control your impulses at the start of changing habits.

- Make the routine difficult: Routines are automatic and easy, so by adding interference or making the routine difficult, the habit is not initiated as easily as it would’ve been. Discard the tools that sustain your habit. E.g., Don’t carry cigarettes with you. Or don’t buy a long charging cable so you cannot sit with your phone for too long.

- Change the environment: The environment usually provides the cues. Changing the environment for a while can help you counter the urge. E.g., Change the habit of eating while working by filling up your desk with productivity tools leaving no space to use the desk for anything else.

- Ask others to disapprove of your reward: Social approval is strong, so ask friends to discourage seeking rewards via the habit. Use an app if it helps. E.g., Ask friends to firmly remind you about your choice to break bad habits and try staying accountable to them.

- Focus on negative consequences: Most bad habits have negative effects, so focus on the magnitude of negative consequences. This will encourage you to change your routine to minimize negative consequences. E.g., Focus on feeling tired when climbing stairs to start exercising regularly.

- Use alternative habits to seek similar rewards: Build new habits to replace others by slowly changing the routine to get the same reward. E.g., Instead of eating to feel satisfied when you get anxious, switch to a tea or exercise or wash your face.

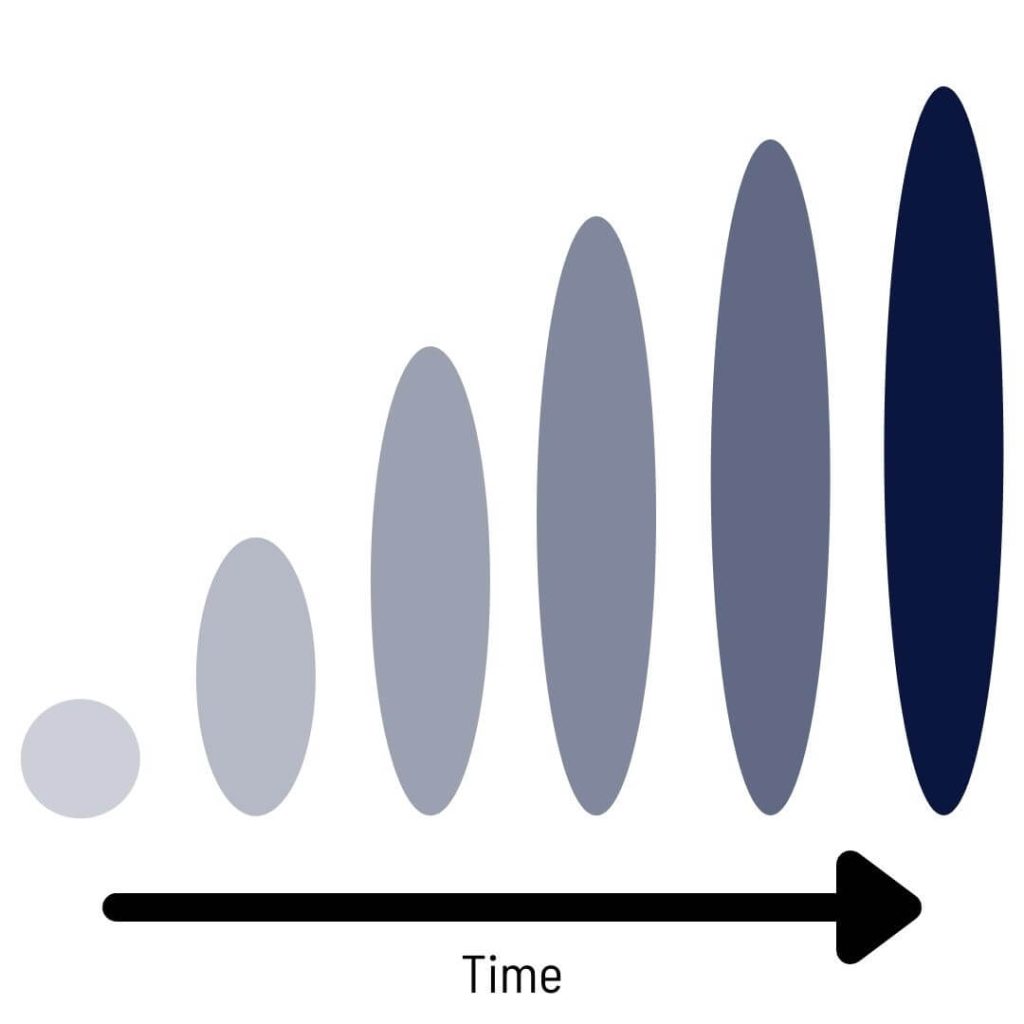

How long does it take to form a habit?

The amount of time it takes to form a habit depends on the person, the context, the activity, the environment, the frequency of repetition, the complexity of the habit, the strength of the cue, the stability of the routine, the strength of the reward, and the motivation to continue it. There is no clear answer but an approximate answer is – anywhere between 1 week and a few months for most people.

A study[19] asking participants to adopt a new eating, drinking, or activity behavior suggests it takes an average of 66 days to form a habit. In their study, the researchers estimated it would take 18 to 254 days for the new behavior to become automatic.

In an exercise program[20] designed to prevent patients or elders from falling, participants acquired the program’s teaching as a habit in approximately 7 weeks.

Another study[21] had 146 participants aged 18-61 years choose a specific new habit to build from 60 including financial, health, environmental, and personal habits (habits like saving money, exercising, recycling, self-care, etc.). Participants’ habit strength increased gradually over the 3-month study period where they monitored their habit with an app. Participants who repeated the habit more had a higher habit strength by the end of the 3 months. Contrary to popular belief, participants’ capacity for self-control did not affect their habit formation.

The belief about what it takes to start a habit and commitment to a habit can impact the time needed to form the habit. It can take just a few repetitions or weeks.

The author of Atomic habits[22] James Clear says the popular idea of forming a habit in 21 days comes from the 1950s when Dr. Maltz, a plastic surgeon, observed his patients took about 21 days to get used to their new faces with changes like a nose job. Some experienced phantom limbs after amputation for about 21 days. This single-clinic observation was marketed by self-help authors and turned into the commonly accepted myth – it takes 21 days to make or break a habit.

Sources

[2]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-15749-004

[3]: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

[4]: https://amzn.to/3zDW5iH

[5]: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8113402

[6]: http://neuroscience.mssm.edu/nestler/nidappg/brainrewardpathways.html

[7]: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/s41039-020-00127-7.pdf

[8]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352154621001406

[9]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16242923/

[10]: https://collaborate.princeton.edu/en/publications/salience-attention-and-attribution-top-of-the-head-phenomena

[11]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352154617301225

[12]: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6864485

[13]: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED076903

[14]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1753-6405.12232

[15]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/001002779390034S

[16]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10810730.2018.1436622

[17]: https://www.proquest.com/openview/bef147f5e649722a48e62b74ff30aaeb/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=105682

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0005796773901198

[19]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.674

[20]: https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40814-019-0539-x

[21]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00560/full

[22]: https://www.amazon.in/gp/product/1847941834?ie=UTF8

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.