When something big happens, did something big cause it? Did the cause of a pandemic have to be a big event? Was a typo in a legal document that cost millions of dollars premeditated sabotage? Does a drunk expression of affection come from romantic love for the person? If you think about these questions, you might notice that we try to estimate the nature of the cause based on observable effects. We sometimes tend to equate or match the magnitude of a cause and its effect: a thinking shortcut called the major-event/major-cause heuristic[1]. It’s also called the proportionality bias, where we assume that effects are proportional to their causes – we show a bias to think large events are caused by large actions, and small effects have small causes. It helps us make quick judgments when we don’t know enough details.

Unfortunately, this not-so-common heuristic might only give us a mentally satisfying explanation when we crave it, not the objective truth. In reality, the causes and effects are rarely proportional to each other.

The major-event/major-cause heuristic (MEMC heuristic) explains simple day-to-day thinking as well as conspiracy theories. In 1962, NASA’s Mariner 1, destined to visit Venus, was ordered to be blown up just 293 seconds after launch. It had lost its course, and the safe option was to terminate the mission. It cost NASA 18.5 million dollars[2] (150 million today). The reason? It must’ve been big, right? After all, it was the cold war; there was a race to make humans a spacefaring species. The actual reason was a typo; possibly a missing hyphen in the guidance system’s code. It’s hard to fathom how something so small can have such big effects.

With the proportionality bias or the major-event/major-cause heuristic, we try to make causes and effects proportional to each other, even when they are not. We actively try to balance the cause-effect relationship by attributing something more to the cause or by dismissing the effect – It’s a tiny virus; what could it really do? Oh, it killed millions, so it must be medical terrorism. If the known cause is weaker than the effect’s magnitude in our knowledge, we find some way to make the cause “heavier.” We do this by adding several things to the low weight of the cause. Examples:

- There is a conspiracy associated with the cause.

- The cause is more intentional than an accident.

- The cause is a part of many other things we don’t know.

- The cause has more emotional significance than it objectively warrants.

- How the proportionality bias leads to thinking errors about real causes and effects

- How we make sense of causes and effects

- We use the representativeness heuristic to make the cause represent the effect appropriately

- We use emotional responses to judge the magnitude

- We justify causes and effects with an energy conservation framework

- Our experiences create a simplified template of thinking

- 4 Ways to overcome the proportionality bias

- Sources

How the proportionality bias leads to thinking errors about real causes and effects

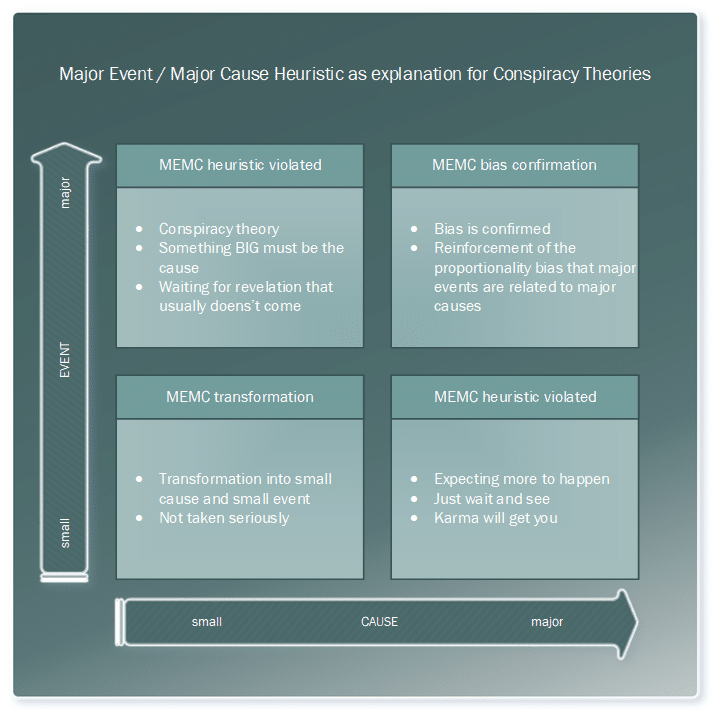

Case 1: The cause is big but the effect is small

The MEMC heuristic is violated and we expect the effect to be larger or we blow it up in our mind just to maintain the proportions. We say things like, “wait for the disaster to happen, it’s going to happen.” or “You’ll face consequences very soon; your karma is going to catch up to you.”

Case 2: The cause is big and the effect is big

The MEMC heuristic turns out to be correct. The few times this is correct, our intuition goes through a confirmation bias and it reinforces the proportionality bias.

Case 3: The cause is small and the effect is small

The MEMC heuristic transforms into a small-event/small-cause heuristic. Usually, since the cause and effect are both small in magnitude, we don’t take it too seriously.

Case 4: The cause is small but the effect is big

The MEMC heuristic is violated and we ascribe something big to the cause, like a conspiracy theory or purposeful neglect or malice. We start believing that the cause is insufficient to explain the event and therefore the cause has to be more. We justify this thinking by believing the cause is a part of some conspiracy theory, a big scheme, a small part of something that is yet to be revealed, or the result of someone’s actions with a tonne of ill will in their heart. This is the most dangerous case because we can easily ascribe negative motives to people who did something wrong that had a bad effect. We jump to conclusions by thinking the person meant to harm or wanted to sabotage something.

How we make sense of causes and effects

Proportional causes and effects might make intuitive sense because they are easy to understand. But, we think of this retrospectively. We think about the causes after knowing the effect, usually. Is it usually possible to learn the exact consequence of every action and make perfect predictions? Is it typical for people to calculate a large sequence of causes and effects that describe real-world events correctly? We wouldn’t have experimental studies or the scientific method if our brains could figure out cause-effect relationships so easily.

The butterfly effect is a notion that a small harmless butterfly could flap its wings and unexpectedly create a massive catastrophe like a storm somewhere else. It’s a metaphor for how small actions can have massive consequences. In a way, the butterfly effect goes against the major-event/major-cause heuristic. NASA’s typo blunder is an example of the butterfly effect. Thinking it was sabotage is the major-event/major-cause heuristic.

The major-event/major-cause heuristic is a sense-making process. We use it to justify or explain events retrospectively in ways we find acceptable. Matching the magnitude of the effects and causes makes more obvious sense to people because it seems simple, elegant, and it kills ambiguity, which humans hate.

In one experimental study[5], researchers found that people tend to assign more blame to a perpetrator if the effect is more tragic. Researchers showed study participants a video of a homeless man falling after being evicted from a police station by an officer. The researchers told participants 4 different things splitting the participants into 4 comparison groups A, B, C, & D. They told groups A and B that the homeless man died in the fall. Group C & D learned that the man survived the fall. They told groups A & C that the police were to blame for the fall but told groups B & D that the man was to blame for the fall. After measuring how intensely the participants were blaming the police or the man and how intense the push was that led to the fall, researchers found evidence for the proportionality effect. Their results showed that people tended to assign more blame to the cop and overestimated the force of the push when the homeless man died.

You may have heard of the Kiki-Bouba Effect – we readily tend to associate the word “kiki” with a zig-zag shape and the word “bouba” with a roundish, curvy shape. The effect is based on an innate cognitive process called cross-modal correspondence. In cross-modal correspondence, we match features to each other based on some characteristic that feels appropriate. In the kiki-bouba effect, the harsher sound of “kiki” matches the zig-zag shape. Similarly[6], we tend to associate bright colors with higher frequency sounds and rough surfaces with distorted sounds. Most people instinctively know when things match each other. The kiki-bouba effect shows that we readily have a tendency to match things, which could transform into matching the right causes with the right effects.

We will now explore this major-event/major-cause heuristic from 4 different perspectives.

We use the representativeness heuristic to make the cause represent the effect appropriately

Humans regularly use shortcuts in thinking. One such shortcut is the representativeness heuristic – people tend to assume 2 things belong together based on how superficially similar they are. So like goes with like; dull belongs with dull; sharp goes with sharp. In a sense, we use the representativeness heuristic to assess how well a cause belongs with its effect. If it’s a big effect, it must belong with a big-enough cause. The heuristic creates an expectation that any event should have a proportional cause.

We use emotional responses to judge the magnitude

If an event creates a strong emotional reaction, it may influence the way a cause is evaluated – not objectively, but emotionally. Then, the cause and effect relationship is proportional to the emotional reaction and therefore appears proportional to each other. In mathematical terms, suppose “A” is the cause, “B” is the effect, and X is the emotional response. If “A” & “B” are proportional to X, by the transitive property, “A” is proportional to “B”. This is a form of emotional misattribution[7] that acts like a shortcut in making evaluations. For example, if your friend is unexpectedly fired from his job, it might anger you. Your reasoning for why it happened will be evaluated through an angry mindset. While evaluating the possible causes, anger may lead to thinking that someone meant your friend harm or he suffered unfairly from office politics. However, the true cause may be something less personal for the employer – cutting costs, poor work performance, downsizing, etc.

We justify causes and effects with an energy conservation framework

People may attribute a Newtonian cause-effect relationship where energy is conserved in the sense that the energy at the start of an event would always be the same at the end, even though it manifests in different forms. Through an associative network of memory, “effort” is a close relative of the word “energy” and might even be interchangeable in some situations. So we end up expecting that the effort needed to cause an event will convert fully into consequences, with little to no loss in “energy.”

Our experiences create a simplified template of thinking

A fourth explanation is ecological in nature. People may learn through experience that increasing the magnitude of a cause typically increases the magnitude of its effect. Better batteries cause a remote control to function longer. Throwing a ball with more force makes it reach farther. Increasing the heat on a stove cooks/burns food faster. The more-more or increase-increase relationships may become a generalized template of thinking called schemas or mental models for evaluating novel information and then intuitively create a big-cause-big-effect assumption. Because these simple templates of thinking model the world we live in, we use them to make good-enough predictions or assumptions.

4 Ways to overcome the proportionality bias

1. Use Hanlon’s Razor – don’t ascribe to malice that which can be ascribed to stupidity

A way to overcome the MEMC heuristic is to use Hanlon’s razor, a philosophical way of thinking. Hanlon’s razor says that we must never ascribe malice or bad motivations to that which is adequately explained by stupidity. By resisting a blame game, it is easier to accept that people could make mistakes unknowingly. If it isn’t stupidity, it could be a lack of knowledge or skill, or it could also be a care-free attitude. If the consequences of one’s actions are bad, it isn’t necessarily due to bad intentions.

2. Think of causes and effects as unlinked independent things

Separate the cause from the effects and treat them separately. Understand what is contextually relevant at any given time. If you are dealing with the consequences, look at them for what they are – not why they are. If you are dealing with the causes, understand the mechanism that plays a role, not the intensity.

3. Pay attention to the mechanisms and intermediate steps

Learn to identify many intermediate steps and contextual factors that connect any event to a specific cause. When we look at all of the details, we realize that the relationship is rarely so straightforward that large consequences result from large actions. Learning the intermediate steps can teach us that things can amplify or minify in a long and complicated process. Remember – hitting a concrete wall with a normal pillow 1000 times will not break the wall. I’ve tried. The effort doesn’t translate into equal consequences. The intermediate steps in energy conversion fail to make a dent in the wall.

4. Be a holistic thinker

Research suggests[8] that individualistic cultures exhibit more proportionality bias than collectivistic cultures. One reason for this is the amount of holistic thinking there is ingrained via culture. The more holistically one thinks, the less one will fall for the major-event/major-cause heuristic. Thinking holistically ensures that the causes and effects are not the only 2 important things to consider. Other important things include the mechanisms involved, the contextual factors, practical concerns, priorities, what realistically matters, what hypothetically matters, what assumptions we make, who it is affecting, etc. All of these factors paint a big, holistic picture. And, thinking in a big-picture mode (called the high-level construal) reduces the emotional intensity of thoughts, making it easier to accept disproportional causes and effects.

Sources

[2]: https://www.rd.com/list/expensive-typos/

[3]: https://twitter.com/FarikoBrainiac

[4]: https://fariko.com/

[5]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10683160600711688?needAccess=true&journalCode=gpcl20

[6]: https://indianmentalhealth.com/pdf/2016/vol3-issue3/Invited_Review_Article_1.pdf

[7]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0146167210383440

[8]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0146167210368278

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.

Well written article that explains much in a very comprehensible manner. Thank you Aditya!