- What is cognition?

- Meaning of cognitive processes and cognitive functions

- List of cognitive functions, processes, abilities, and related concepts

- The executive functions

- Intelligence, skill, and learning through top-down and bottom-up processes

- Deeper layers of cognition

- What are cognitive abilities?

- Where does cognition happen in the brain?

- What are cognitive resources?

- What do cognitive psychologists and cognitive scientists do?

- Hypocognition and Hypercognition

- Sources

What is cognition?

Cognition refers to all mental processes that lead to thoughts, knowledge, and awareness. The underlying mechanisms are called cognitive processes. They govern cognitive functions like attention, pattern-matching, problem-solving, memory, learning, decision-making, language, mental processing, perception, imagination, logic, strategic thinking, etc.

The word cognition comes from the Latin word cognoscere which means “get to know”.

Meaning of cognitive processes and cognitive functions

Cognitions come in layers of processes and components. Think of it as a Rubik’s cube which is meaningful even if it is unsolved. Each square represents a cognitive process and any type of final arrangement (proper solve, mixed color patterns) represents cognitive abilities or cognitive functions.

- Cognitive processes are mental processes that help us interact with the world and interpret our experiences.

- Cognitive functions are higher-order mental abilities such as learning, memorizing, decision-making, creative thinking, moving, speaking, and problem-solving.

Cognitions (a fancy term for thoughts) are often assumed to be verbal thoughts, but they also include other forms of thinking such as auditory imagery (mental sounds), visual imagery (mental pictures), and kinesthetic imagery (mentally perceived bodily sensations). Notice that cognitions (with the “s”) typically indicate thoughts and cognitive processes/functions/abilities indicate all other processes given below.

APA definition of cognition

The American Psychological Association defines cognition as “all forms of knowing and awareness, such as perceiving, conceiving, remembering, reasoning, judging, imagining, and problem-solving.” Along with affect (emotions) and conation (motivation, intent), it is one of the three traditionally identified components of the mind.

You can view the following terms as cognitive processes (the smaller units of cognition) as well as cognitive abilities (overall competence in a type of cognitive process). These are examples of cognition in a holistic sense – a person’s overall cognitive capacity. Genetic tendencies, biological make-up, past learning and experience, expectations, skills, expertise, motivation, emotions, sleep, diet, well-being, etc. influence these.

- Sensation: Information entering our sensory system. Read more

- Perception: The processing and interpretation of signals from the senses as well as signals generated internally by the brain.

- Learning: Acquiring and demonstrating a reliable tendency to do something new. It is the process of acquiring new knowledge in a way that can be used in the future. That means learning occurs when we modify previous cognitions & behaviors or acquire new cognitions and behaviors. Read more and more

- Memory: Ability to acquire and store information. Learning and memory are similar in the sense both require relatively stable changes in neural networks. Memory is a global mental phenomenon that simply means changes in neural structures that represent information and make it coherent. And learning is the process of building those changes. All sorts of cognition, including learning, use “memory units.” Memory is verified and re-created by the process of remembering. The process of recognizing verifies memory. But memory also influences us unconsciously, through associated feelings. Read more

- Gnosis: Ability to recognize things you’ve already learned via the senses: People, cars, foods, etc.

- Praxis: Ability to move your body in meaningful and goal-directed ways: Darting, dancing, sex, music, mixed martial arts, etc.

- Thinking: A process where the mind actively creates meaningful sequences of symbols. These symbols are usually the same as languages (internal dialog), mental images, and involve shifting attention toward internal and external information. These symbols are typically reliable and constant, such as words, shapes, and colors. Read more

- Processing speed: The speed of processing information. Depends on past experience (learning), access to memory, the strength of neural connections needed, and working memory capacity.

- Priming: The influence of something on future cognition.

- Attention: Ability to prioritize one type of information over some other type. The brain avails maximum resources to deal with this prioritized information. Read more

- Salience: Ability to focus and make something more pronounced, through words, attention, and memories.

- Observation: The ability to pay attention and recognize aspects of the environment (and in the mind)

- Vigilance: Careful attention, usually with salient & primed information.

- Awareness: Recognition of cognition. It is the continuous monitoring of one’s thoughts and perception, a part of metacognition.

- Heuristics: Mental shortcuts and tendencies to think in particular patterns. Like learning moves in chess.

- Biases: Tendencies to think in a particular but warped way. Biases create a tendency to pay attention to a particular type of cognition over other types. Like the negativity bias that highlights negative events more than positive ones. Read more

- Perspectives and mental rotation: Ability to manipulate your point of view of a situation or object. Cognitive empathy is a higher-order version of this.

- Creative cognition: A set of cognitive processes that underlie creative work, including divergent thinking, convergent thinking, construal levels, mental models, etc. Read more

- Spontaneous cognition: Thoughts that pop into the mind when it is relatively idle and the default mode network is active. Read more

- Social cognition: All forms of cognition that involve other people and social concepts like relationships, groups, judgments, popularity, bullying, morality, etc. Read more

- Auditory cognition: Cognitive processes based on auditory information – speech, sounds, vocalizing emotions, musical ability, recognizing unique voices, reading subtitles with foreign audio, etc.

- Visual cognition: Cognitive processes based on visual and spatial information – colors, shapes, arrangements, locations, directions, gradients, stimuli-based details, etc.

- Meta-cognition: Thinking about thoughts and cognition about cognition. Read more

To simplify many aspects of cognition[1], researchers classify cognition as hot cognition and cold cognition. Hot cognition involves emotions and motivation. Cold cognition is more neutral, raw information processing. Within both these categories, all facets of cognition are roughly divided into 4 categories: Sensory-Perceptual processes, Attention, Memory, and Executive functions (cognitive control).

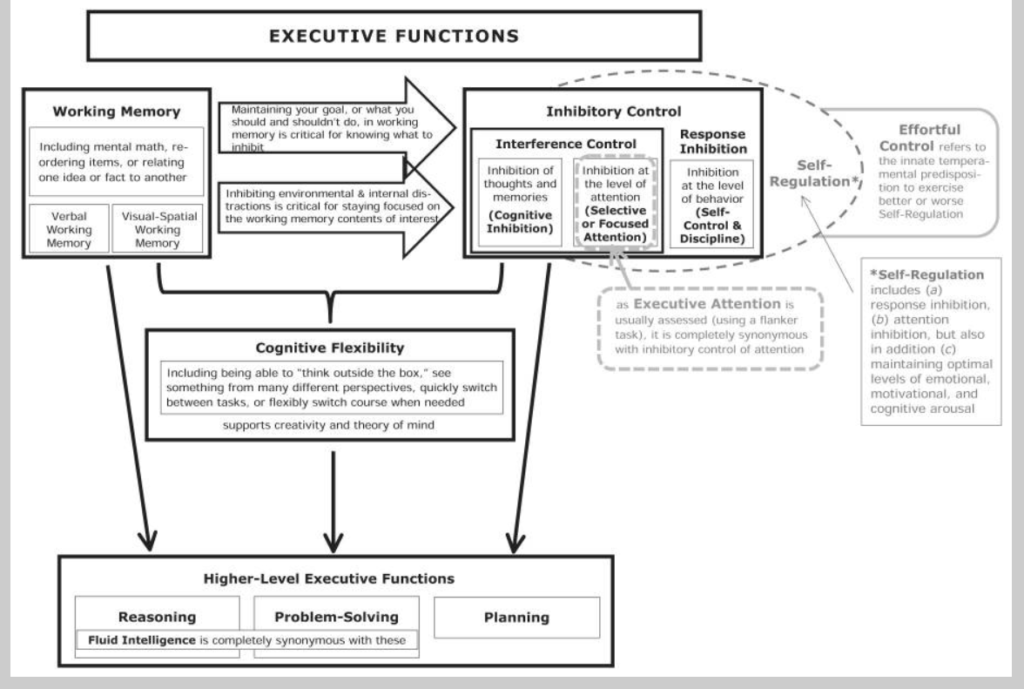

The executive functions

Further down the cognitive assembly lies a core set of cognitive processes called the Executive functions (cognitive control) that help us guide, plan, initiate, stop, monitor, and modify our interactions with the outside world and the inside world. This is like a management team or the “executive system” for all aspects of cognition and behavior.

Definition: According to Raymond C.K. Chan, David Shum, Timothea Toulopoulou, Eric Y.H. Chen[2] “Executive functions” is an umbrella term for functions such as planning, working memory, inhibition, mental flexibility, as well as the initiation and monitoring of action. Executive functions are flexible, goal-directed, and adaptive cognitive functions. They are usually most engaged in novel, challenging situations.

The executive functions help us bring ideas into awareness and think. They help us have meaningful conversations.

The core executive functions

The core executive functions work together, not in isolation.

- Attentional control (concentration, distractions) – Choosing what to focus on and what to ignore. Also known as “Executive control of attention.” It helps us orient ourselves, stay alert, and resolve conflicts between options to focus on. There are 2 types of attention.

- Exogenous attention: Something grabs your attention. Automatic, bottom-up, stimulus-driven, involuntary. This attention is usually not considered an executive function but remains a core cognitive process.

- Endogenous attention: You focus your attention. Purposeful, top-down, goal-driven, voluntary

- Selective attention: The ability to select what to focus on and what to ignore.

- Divided attention: Splitting attention and managing information from 2 or more areas that we concentrate on. This is what we do while multitasking.

- Working memory (temporary storage of information) – Remembering an OTP or phone number. The temporary storage of memory is not static, it is dynamic and we can manipulate information in it in real-time. There is usually a limit to the capacity of working memory.

- Verbal memory/phonological loop: Short-term memory for language, sounds, comprehension, etc.

- Visuospatial sketchpad: Short-term memory for visual details, locations, space, and relationships between objects.

- Episodic buffer: Short-term holistic memory system + Capacity to process information coming from all parts of the brain that influences short-term memory.

- Inhibitory control (stopping of a thought or impulse) – Stopping an automated response or exogenous attention. Self-regulation (adjusting oneself) is the parent of inhibitory control which includes motivation, emotions, and behavioral patterns.

- Response inhibition: Stopping ourselves from doing something impulsive.

- Interference inhibition: Regaining attention to focus focus, stopping thoughts. Also called cognitive inhibition.

- Cognitive flexibility (shifting mental gears, taking new perspectives) – Switching back and forth between tasks and ideas without losing insight into what we are thinking. High cognitive flexibility also allows us to inspect an idea from multiple perspectives or levels of processing (construal levels) and have multiple simultaneous thoughts. Cognitive flexibility is closely related to creative thinking and higher-order problem-solving too.

While traditional views[3] look at attentional control or executive attention as a small component of the other 3 executive functions, some researchers argue[4] attention (or focus) is another executive function.

These core cognitive functions (or executive functions) help us build higher-order executive functions by drawing additional “resources” from our previous learning & memory. So Higher-order executive functions are a combination of the core executive functions which use “knowledge” units from what we have already learned or can remember. These knowledge units include everything from language, experiences, memories, expectations, and emotions.

One example of higher-order executive functioning is browsing Amazon and choosing the best product to buy. It uses working memory, inhibitory control to not impulse-buy, attentional control to keep track of what’s important, self-regulation to deal with your budget, cognitive flexibility to compare different products, and rely on past learning such as an experience with a brand and memories of conversations with friends regarding recommendations.

The higher-order executive functions

- Relational reasoning and logic: Comparing and relating ideas to see what’s logical. It includes understanding facts, guesses, and conditions like IFs, ANDs, ORs, and BUTs. Rational thinking is a type of relational reasoning.

- Decision-making: Weighing pros and cons, choosing the top 3 options, ignoring the worst, settling on a compromise, etc.

- Planning: Remembering to remember (prospective memory), making predictions, gathering resources to do a task, reviewing your plan, identifying where you’d need to improvise, etc.

- Problem-solving: Understanding the components of a problem, breaking down or reframing problems, gathering resources to solve them, identifying optimal or economical solutions, etc. Playing puzzle games like chess and sudoku are high on problem-solving.

Adele Diamond developed a model of executive functions. You can read the original paper here[5] or refer to the diagram below (also from the paper).

Intelligence, skill, and learning through top-down and bottom-up processes

According to Adele, fluid intelligence – a type of intelligence that describes one’s ability to think, plan, and reason – is the same as the higher-order executive functions. The other aspect of intelligence called crystallized intelligence is more about your experiences and past learning.

They are both related but different based on the role executive functions play. Neuroimaging studies[6] show that people who do well in new tasks that require executive functions have high activity in the lateral prefrontal cortex. But when the tasks get familiar, the ones who perform the best use the lateral prefrontal cortex the least. So when the task is familiar, the need for executive functions drops.

We can view some executive functions as a Top-Down control system where we exert executive control (top) on the information or work we are doing (down). If a task is new or someone is learning a new skill or learning a new topic, top-down control can be helpful. But for those who have practiced a lot and have the experience, top-down control can hamper performance. Once learning takes place, it becomes automatic with new neural connections dedicated to that learning. So a top-down approach interferes with it by overriding past learning. This is why experts and skilled people can rely on their gutfeel and perform well but asking them to monitor and evaluate their process can hamper their performance.

Just like “Top-Down” processes, some executive functions rely on a Bottom-Up approach. The core executive functions of “attentional control” and “inhibition” often depend on features of the stimuli like size and shape. (stimuli is anything that has the potential to modify mental activity.) Distractions, overwhelming sensations, random repetitive thoughts, etc. exert bottom-up control over our cognition.

Bottom-Up control and Top-Down control are rarely isolated from each other. For example, while studying, loud sounds can exert Bottom-Up control, and then other cognitions like remembering your goals can exert Top-Down control and remove distractions.

Intelligence is made from many layers of cognition and cognitive abilities like reasoning, verbal skills, planning, logic, and mathematics. Intelligence isn’t a single stand-alone “module” because multiple types of intelligence like musical intelligence, social intelligence, and practical intelligence are built from the same cognitive functions or executive functions

Deeper layers of cognition

The deepest layer of cognition is abstract and full of theoretical cognitive structures that explain all forms of cognition. These include sensory abstraction, cross-modal correspondence, estimations, simulations/predictions, smallest bits of data and how it transforms, cooperation and competition between sensory inputs, conversion of sensory inputs to perception, etc.

These layers of cognition aren’t necessarily a hierarchy. They have feedback loops between each other, and they often work as a whole system. Usually, along with factors like behavior, emotions, environment, society, instinct, and genetics. Such as intelligence and creativity. Cognition, especially as a system that connects reality to the inner mental space, is a big part of understanding consciousness.

What are cognitive abilities?

Cognitive abilities are cognitive processes and groups of cognitive processes that can be measured in a meaningful way. In easy words, everything under cognition can be a cognitive ability if you can measure it for practical benefits. Cognitive abilities can be[7]improved, so they are cognitive “skills.” See how you can cognitively train to play the guitar better.

How are cognitive abilities measured?

Usually, most cognitive abilities are measured through tests that require a person to do a task which indicates a person’s cognitive capacity. For example, the digit span task measures working memory for numbers. In that task, a person is asked to recall a sequence of digits and scored on accuracy, errors, and time.

More complex cognitive abilities include the measurement of short-term memory as well as attentional control and interference inhibition. One such task is the n-back task where a person has to remember symbols that appeared n rounds ago. In a series of random pictures, one would need to indicate when a particular photo appeared 2 rounds ago. This task can get more complex through distractions or by asking a person to report images seen 5 rounds ago.

Musical ability, mathematical ability, verbal ability, reasoning, pattern-matching, problem-solving, etc., are higher-order cognitive abilities that involve all of the core executive functions as well as previous learning and memory. Cognitive abilities are like higher-order executive functions applied to a specific theme.

Intelligence tests and creativity tests are combinations of multiple cognitive abilities. So are tests like the Gibson test of cognitive abilities. More common examples: Cognitive reflections test, Weschler’s intelligence tests, Stanford-Binet tests, Stroop tests, Raven’s progressive matrices.

Where does cognition happen in the brain?

The current theories look at the whole cerebral cortex (the folded region of the brain) as the primary area of cognition. It is divided into 4 broad theme-based regions.

- The frontal lobe of the cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex, is vital for higher-order cognitive abilities and executive functions.

- The parietal lobe is involved in sensation and perception.

- The occipital lobe is involved in visual cognition.

- The temporal lobe is involved in consolidating memories, speech, and auditory data.

Memory + learning, on the other hand, is widely distributed across the brain. The current understanding is that all forms of neural changes account for various types of learning and memory: Long-term memory, knowledge of facts, smells, song lyrics, skills, language, etc. Memory is like a vast network of densely connected “features.” For example, the spreading activation model of memory describes memory as millions of multi-colored spider webs with each color representing closely related information and each intersection representing individual “units of memory.”

A rough neurobiological hierarchy exists for cognitive functions. Cognition, broadly speaking, is our brain’s information processing ability. With that in mind, perception and sensation is a rapid form of information processing. It typically occurs in sub-cortical and posterior cortical regions. Attention works on all levels of processing. Higher-order executive functions like decision-making and problem-solving are a more complex form of information processing that works on pre-processed information in more evolutionarily young cortical regions.

Research in cognition usually moves toward grounding measurable abilities in identifiable neurobiological circuits.

What are cognitive resources?

A number of psychological theories use the word “cognitive resources” to explain away some unknown “demand”. For example, a positive mood can enable more cognitive resources. Or curiosity and fun increase cognitive resources for learning. So what exactly are cognitive resources?

- Knowledge structures: Individual meaningless units and larger useful units of connected information that form the context.

- Biological resources: Availability of a neurotransmitter at a synapse, activity in a brain region, consumption of glucose, glial cells, recruitment of additional neural structures to help current processing.

- Mental resources: Relying on old knowledge structures that help current thinking.

- Blocking resources: Emotions and other memories can block us from remembering something. Like in the tip-of-the-tongue syndrome where all related details block the desired word. Emotions like fear can also limit thinking.

- Attentional scope: A person can have narrow attention that highlights finer details or have broad attention that focuses on the overall concept and global essence. The nature of attention is a cognitive resource.

- Access and availability: Not everything we have learned or have in memory is accessible. More resources mean higher access to that which is already present.

- Housekeeping: Sleep, idle time, and relaxation usually permit the brain to undergo maintenance and pre-determined “clean-ups” of neural structures. Some of this could be building the myelin sheath on axons to make a neural connection faster. Or, isolating a few important neural connections from the previously used many to “down-size” a network to its maximum biological efficiency.

Apart from these, cognitive resources also refer to the deepest layer of cognition we discussed in the previous section. Those cognitive structures aren’t necessarily meaningful but can be useful in current processing. For example, spontaneous thoughts that pop into an idle brain can help with creativity because the default mode network accesses large amounts of brain networks that may represent useful knowledge.

What do cognitive psychologists and cognitive scientists do?

Cognitive psychologists study the mind at various levels of cognition, usually through carefully conducted experiments that tease out a particular process. They then create “models of cognitive processes” based on that data. Theories of memory and learning have a direct influence on applications like education, artificial intelligence, marketing, advertisements, therapy, mental health, and rehabilitation. Check out these therapy insights based on cognition.

Learning, memory, intelligence, decision-making, cognitive biases, and creativity are some of the most commonly studied cognitive phenomena since the popularity it gained in the 1940s and 50s. This popular thrust was an intellectual movement called the cognitive revolution. It began to uncover the secrets of the mind and the processes within.

Cognitive psychologists usually take up academic and R&D positions after earning a Ph.D. Other psychologists and scientists focus on aspects of cognition based on their areas of interest like music, UI/UX, product design, education, artificial intelligence, sports, self-help, leadership, etc. Everything about humans can have a cognitive perspective, even artificial intelligence and theology.

Related areas: Linguistics, cognitive science, computing, cognitive neuroscience, neuroscience, social psychology, philosophy, mathematics, artificial intelligence, animal cognition, and education.

Hypocognition and Hypercognition

When we don’t have the cognitive tools, or we lack the words to understand something, we are in hypocognition. In hypocognition, we do not possess the mental tools to comprehend or perceive something. For example, many people were in a state of medical hypocognition before the COVID pandemic began. We are also in a state of hypocognition to speak about consciousness.

When we overapply a cognitive structure where it isn’t appropriate, we are in a state of hypercognition. For example, applying metaphors like “finding myself” to a physically, uniquely located you.

With this post, I hope you are no longer hypocognitive about cognition:)

Sources

[2]: https://academic.oup.com/acn/article/23/2/201/3079

[3]: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

[4]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00058/full

[5]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4084861/

[6]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16242923/

[7]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1041608016300231

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.