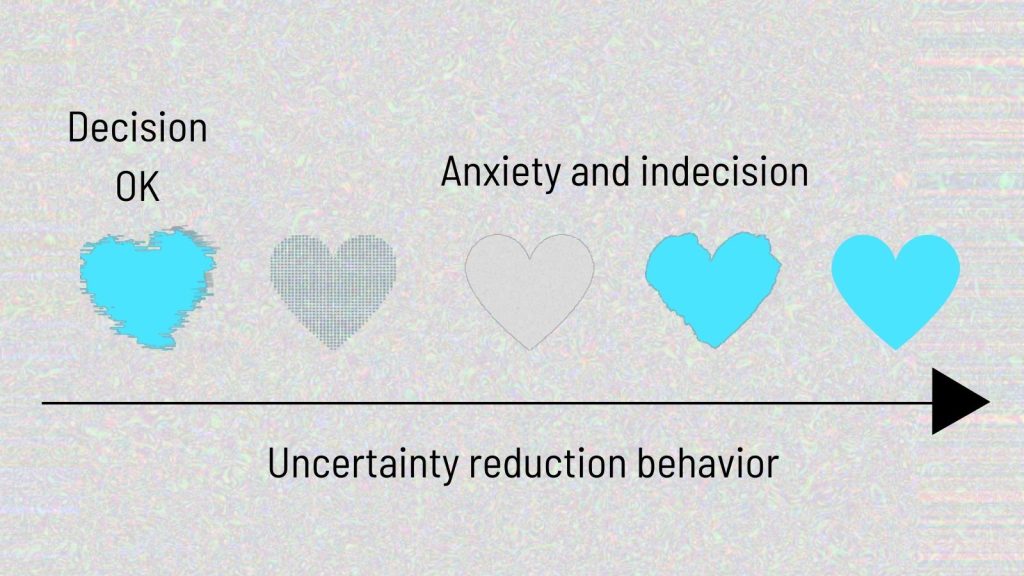

Have you gone online to check reviews and gather information before you make simple decisions about what to watch or eat? If yes, you’ve engaged in uncertainty reduction behavior. Sometimes it’s healthy, but other times, it creates second-order anxiety and poor decisions. Here’s what to do instead.

What is uncertainty reduction behavior?

Any behavior that reduces uncertainty before making a decision or judgment is an uncertainty reduction behavior. Uncertainty here means a situation can’t be fully understood, predicted, or analyzed. This is ambiguity in a context, and people attempt to reduce it in whatever way they can. Sometimes, the simplest and healthiest way to reduce ambiguity is to learn more about a situation. However, after a point, it becomes unhealthy because learning more information becomes a source of more uncertainty.

Uncertainty reduction behavior is common in those with high anxiety. Anxious people may engage in habitual behavior that uses energy to determine and predict the outcome of a decision. Anxiety is a response to uncertainty and threat. But it also comes with higher attention to uncertainty and threat[1]. So anxious people engage in anxious behavior that attempts to reduce uncertainty. However, the behavior itself can cause more anxiety and hamper decision-making.

Uncertainty-reducing behavior is anxiety-reducing behavior, which is also certainty-increasing behavior.

Healthy vs. Unhealthy uncertainty reduction

Uncertainty reduction behavior ranges from healthy to unhealthy, where healthy is just learning more to make rational decisions, and unhealthy is spending too much time/money/energy on reducing uncertainty when not required. In most cases, uncertainty reduction is motivated by fear. Being afraid of disappointment, wasting resources, not enjoying, plan failing, etc., motivates behavior to reduce uncertainty. Learning more about a product is generally healthy, but spending 2 hours reading every review there is on the internet to watch a 2-hour movie isn’t – that’s more time than an average movie. Either way, you’d lose 2 hours.

Uncertainty in relationships

In an interpersonal context, the uncertainty reduction theory (different but related to this article) says human communication begins with a set of methods to reduce uncertainty. Two people would systematically increase specific behavior to reduce uncertainty via questions, background checks, small talk, social media interactions, and shared experiences. For relationships, reducing uncertainty is generally healthy because the consequences can be dire.

Examples of uncertainty reducing behavior and resulting anxieties

Here are some examples of anxious behavior that attempt to reduce uncertainty but often ends up causing more anxiety. These are a problem only if they magnify anxiety. If there is no second-order anxiety coming from these behaviors, chances are the behavior is not yet problematic.

But first, we need to know if the uncertainty reduction behavior is problematic or not:

- If it is problematic, you spend too much time before arriving at a decision, or get conflicted about indecision, or spend too much time finding answers that only frustrate you, or new information causes more anxiety. It’s also problematic when all that effort doesn’t change anything.

- If it is not problematic, you are essentially only preparing and learning more. In a way, it’s a part of planning and rational decision-making.

The next examples list behaviors and potential problematic anxious thoughts associated with the behaviors.

1. Looking up symptoms online when you feel something is off (cyberchondria) – When you get an answer, there is more anxiety.

- Is this real?

- What if my case is different?

- How bad can it get?

- What should I eat/drink/do now?

- Should I take a pre-emptive medicine?

2. Googling the menu before choosing a restaurant only to know it didn’t surprise you – you see the menu, you have more indecision than you had before.

- Do I really want XYZ cuisine?

- What if it tastes bad?

- What if it’s not available?

- How should I choose – so many options?

3. Snooping on other’s mobile activity – after seeing what they are doing, you’d have more questions – more uncertainty.

- Why are they on the phone right now while I am talking (phubbing)

- What are they getting from this? Money? Ego-boost?

- Are they bored? I am boring them?

4. Watch too many previews and fast-forward a movie before watching it to see if it’s worth it – doing this might kill the fun and cause indecision.

- Is the preview the best part of the show?

- Will the rest disappoint?

- Now I know what happens, Should I choose something else? let me preview that.

5. Stalking your date on all socials to know what you are getting into – gaining this information may form too many preconceived notions that sabotage a potential relationship

- Why is this person not posting on any social?

- They have no personal information; what if the person is a weirdo?

- They look outgoing, but what if they are just portraying a good image?

- What if they aren’t what they seem?

What causes uncertainty-reducing behavior?

There are some fundamental ways in which people react to uncertainty. People are generally averse to uncertainty and ambiguity and prefer safer decisions when comparing options. This is called ambiguity aversion[2]. They tend to avoid making any uncertain decision and choose the least uncertain one when forced. We often choose food items we know we love and do not take a risk on different items. We do the same with online purchases. Once we know we can trust a brand, we stick with it and avoid potentially better products from an unknown brand.

We are also heavily motivated to increase certainty. One such way is the zero-risk bias[3]. Suppose you have 2 options. In option A, your behavior would reduce uncertainty from 20% to 0%. In option B, your behavior would reduce uncertainty from 50% to 10%. You eventually have to choose both options, but you can only do something about 1. Would you choose option A or option B?

It turns out we choose option A because it eliminates the risk. We consider fully eliminating a risk more valuable than a large reduction in total risk. So here, we irrationally value 20% risk reduction more than 40% risk reduction. This problem occurs in many forms in daily life. You may complete a task that is close to completion first instead of using the same time to progress halfway through another task. You may choose to charge one device to 100% instead of charging another one to 50%.

Uncertainty reduction behavior occurs more when a person has the following 4 tendencies. These are strongly related to anxiety.

- Low tolerance for uncertainty: Tolerance for uncertainty is a general tendency to be ok with uncertain scenarios. People vary in how they handle uncertainty and how much they are ok with uncertainty. For example, exploring a new cuisine without knowing anything about it is a sign of high tolerance for uncertainty. Not trying out new foods is a sign of low tolerance for uncertainty.

- High need for cognitive closure: Need for cognitive closure is a tendency to gain information to have conclusions and definite answers. For example, visiting multiple doctors to get the same diagnosis is a need for cognitive closure. When doctors do not give the same diagnosis, the need for cognitive closure is unmet. Then, the person continues seeking cognitive closure till there is one definite answer.

- High regret aversion: A need to avoid potential regrets is strong in most people, and it motivates them. Buying insurance is a common example to avoid costly medical bills.

- High need for safety: A need for safety comes with a need for predictability and damage control. It contains behavior that tries to minimize unknown problems and increase coping with known problems. For example, knowing food ingredients to manage health is a safety-seeking behavior, where one knows it’s safe to consume that food in case of allergies.

Maintaining mechanisms

One fundamental reason for having any of these tendencies is a particular reinforcement cycle. In a reinforcement cycle, any behavior has a reward (reinforcer) or a negative consequence (punishment), which either increases the frequency of behavior or decreases it. When an unprepared person doesn’t know enough and faces severe consequences, the likelihood of future unprepared behavior reduces – so uncertainty-reducing behavior increases as a coping mechanism. When the coping mechanism of learning more, going through reviews, finding out minute details, deliberating over decisions with lots of pros and cons and advice, etc., works, uncertainty-reducing behavior becomes the default response while making decisions.

Similarly, going prepared and knowing everything produces many direct rewards. This increases the likelihood of future uncertainty-reducing behavior too. For example, if you are positively reinforced by gratitude when you spend hours searching for the perfect movie and seeing if it is worth it, you’d continue the behavior in a similar context. Over time, this becomes a habit, and uncertainty reduction behavior becomes the default response to decision-making.

Managing the anxious pattern of uncertainty reduction

To reduce second-order anxiety caused by uncertainty-reducing behavior, retrain your brain to notice rewards via ambiguity.

1. Notice how not knowing turned out great.

Value surprising outcomes. Human behavior tends to increase or decrease most dramatically when the rewards are uncertain. This is why gambling and social media are addictive – you never know how much money you might win or what amazing notification you might get. There is always a possibility of an unexpected reward.

Essentially, if you acknowledge these surprising rewards, your behavior to enter uncertain situations that give rise to rewards increases. This means you are less likely to reduce uncertainty when the value of potential rewards is high. So focus on surprises and the joy/reward they bring. By definition, they are rewarding because you didn’t know they were coming your way. Acknowledge (or write down) when you entered an uncertain situation, and things turned out well.

2. Have fallback options but take chances.

Having fallback options is a good security net. When you enter an ambiguous situation, think of an escape route only if the uncertain situation turns out bad. This way, you can take chances without feeling stuck in a bad situation. For example, you can go and check out a new restaurant and if it doesn’t vibe with you, have a plan to go to a place you like.

Use backup safety nets to explore new experiences and recalibrate your uncertainty reduction habits. After learning it’s not always bad, you may reduce your uncertainty reduction behavior.

3. Trust heuristics and ignore analysis.

The downside of analysis is overthinking. The second-order anxiety from uncertainty-reducing behavior (discussed above) is an example of overanalyzing and overthinking. In this case, it’s best to avoid analysis and use specific decision-making shortcuts called “heuristics”. Use heuristics because they are good decision criteria in most cases. There are certain heuristics that may help anxious people make decisions without the need to forcibly reduce uncertainty. They are easy, and they offload the burden of reducing uncertainty to something/someone else. For an anxious person, this is a win. It reduces the need to reduce uncertainty but also creates ways to reduce it without extra effort.

4 anxiety-friendly heuristics for non-life-altering decisions

Rely on these heuristics if you feel compelled to engage in anxiety-reducing behaviors.

- Mood congruence: Does the decision match my desired mood? Use a simple filter to see if your future mood matches your decision. Look for emotional congruence – if you are in for an exciting period, let go of uncertainty reduction behavior because your desired mood of “excitement” is compatible with uncertainty. If you want your comfort zone, pick something that gives you emotional signals of comfort. In any case, use your emotions to choose your decision because uncertainty reducing thinking after a gutfeel worsens decision-making[4]. This will recalibrate your instinctive decision-making to rely less on uncertainty reduction. Emotion-congruent decisions will also feel more subjectively appropriate[5], leading to less thought about whether they are right for you or not.

- Social proof: Are others liking it? Chances are, what the majority likes is at least acceptable. This works well with movies, food, products, and even larger decisions like buying/renting a house and choosing a vacation spot. Uncertainty reduction might cause unnecessary confusion about small things and take your focus away from important details.

- Trusted source: Did someone I like/admire recommend it? You can offload your decision to someone else by asking for their recommendation. If you implicitly trust someone because you like them or think they are an expert, follow their advice. Since anxiety creates self-doubt and mistrust for random recommendations, already liking/respecting the decision-maker can help – you’d readily accept their recommendation. Moreover, you may have already trusted them after vetting their decision-making ability.

- Empathy: What would XYZ person choose? Empathy creates models of other people in the brain. These models include their tendencies and preferences too. So asking yourself what someone else would choose will give you access to their thought patterns and think from their point of view. This can be an easy way to resolve a decision.

These heuristics will:

- Reduce the feeling of taking random chances with your decisions.

- Ground your decision-making in things you already know without seeking complex details.

Sources

[2]: https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/110/3/585/1859203

[3]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-30652-004

[4]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51189959_Should_I_Go_With_My_Gut_Investigating_the_Benefits_of_Emotion-Focused_Decision_Making

[5]: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Femo0000490

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.