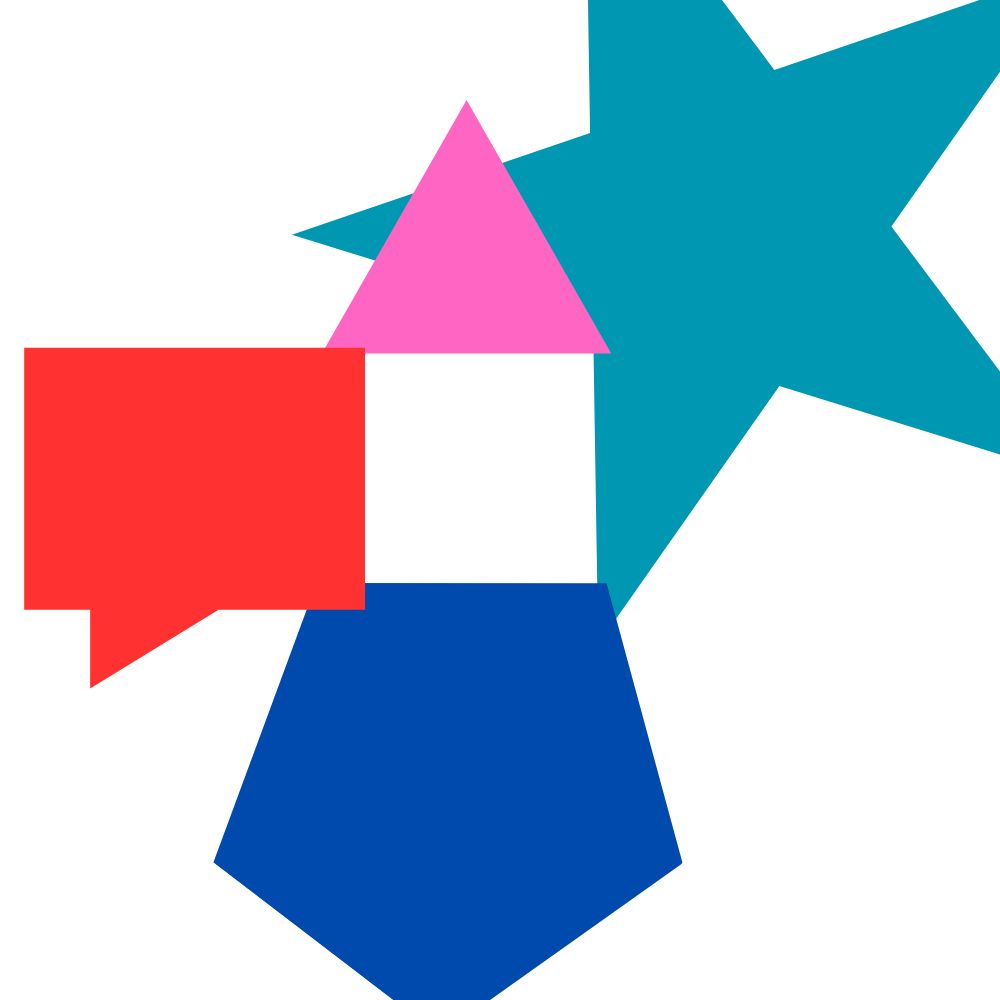

Make a square without using squares, lines, or rectangles.

This is the essence of improvisation. I looked at the rule – make a square without certain shapes. I used a design tool. I selected options not specified in the rule (star, triangle, dialog box, pentagon) and found alternate uses for those shapes. The square is perceived as a negative space.

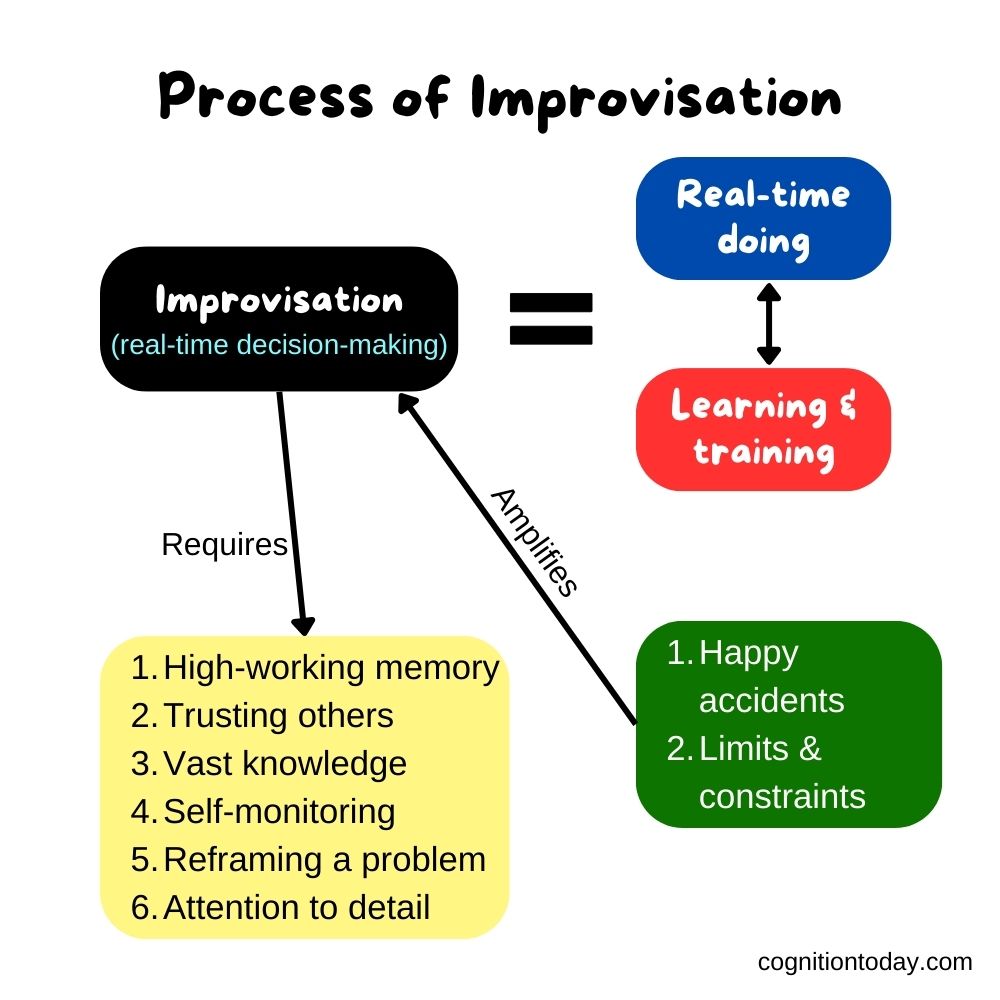

Improvisation, or real-time decision-making[1], is thinking on the spot to find solutions without any preparation using available information and tools in novel ways. Improvisation is not just for the creative genius or a creative personality. It is a practiced skill that anyone can learn.

Not preparing in advance is a little bit of a misguided way to describe improvisation. Practice and previous experience is almost always necessary to successfully improvise during a performance or some form of planning.

When do people generally improvise?

- When a travel plan doesn’t work out, and you must re-arrange your itinerary and change your plan at the last minute.

- When food ingredients are missing, and you still have to make a meal.

- When musicians are in trial and error mode of a way to finish their song before they finalize it.

- When a brainstorming meeting requires decisions made during the meeting.

- When a route is closed, you have to choose an alternate path to get to work.

- When a performer (actor, musician, athlete) is asked to try out something new.

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure, and the by-product from one food can be perfect for making another.

Yotam Ottolenghi[2]

Cognitive requirements to improvise well

Improvisation requires high working memory, self-monitoring, vast knowledge, a clear way to reframe problems, attention to detail, and trust.

Tip: You can start improvising in everyday life by trying to solve problems by using whatever you find around you, even if it isn’t the best option. Don’t wait to find the best method and ingredients to solve a particular problem. Access what’s available to you and work with just that.

- High working memory: Working memory is our ability to hold information in our minds at any given time. It’s the act of continuously remembering something and keeping it in awareness for as long as needed. Typically, humans remember a few items at a time for a few seconds. Improvising requires us to remember as much as we can at any time to apply that information and update it on the go.

- Self-monitoring: Improvising requires us to monitor ourselves while we are in a creative process. We need continuous feedback from ourselves, others, the environment, and how the solution unfolds. Self-monitoring allows us to constantly update our perspectives and approach to problem-solving, without which we would be clueless about how our solution works. In simple words, self-monitoring —> continuous adaptation.

- Vast knowledge: Vast knowledge – both tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge – is needed to use that information while improvising. Knowledge is stored as a network of connected information. On-demand accessing that knowledge is necessary to improvise. So having it isn’t enough, having the confidence to remember it is equally important. A general habit of learning and keenly observing your experiences is a good way to build tacit and explicit knowledge.

(Tacit knowledge = hard to explain knowledge that comes with experience.

Explicit knowledge = what you consciously learn.). - A clear way to reframe a problem: We need to improvise when new problems emerge or existing problems unexpectedly change. In some cases, the resources to handle a problem change, and sticking to a known strategy isn’t feasible. So, to improvise, you have to reframe and regularly assess the situation to update your approach.

- Attention to detail: Since our brain focuses on only a small portion of information at any given time, we need to deliberately pay attention to many minute details and keep a big-picture perspective, and still isolate details. To develop your attention to detail, practice being observant in day-to-day events.

- Trust: Improvising requires trusting other people to help you. It also requires trusting your judgment and abilities. This trust often lays the foundation for feeling confident in improvising.

How people learn to improvise

Researchers have built an elegant 2-step approach for improvisation: Real-time doing + learning & training.[3]

- Real-time doing is us making decisions on the spot by acting and reacting to a situation.

For example, improvising at a marketing meeting will be responding to others’ ideas by building upon them (reacting) and putting forth ideas (acting). - Learning & training is an ongoing process where people acquire skills by example and practice, which gives them the meta-skill for “real-time doing.”

For example, in that marketing meeting, learning & training would be past experience and learning other’s marketing examples on which you build new ideas.

What about intuition? Doesn’t intuition guide improvisation? Our experience is typically intuitive while improvising, that is because we’ve made a habit of “real-time doing” after having a lot of experience in “learning & training.”

The theories above explain what’s happening in the mind during improvisation. But they do not clearly say what people have to do while improvising a skill. So, let’s apply the 6 requirement factors using the 2-step approach for tips on improvising in Music, Cooking, and Acting.

Music Improvisation (Piano & Guitar)

- Listen closely: Music is very short-term memory intensive and relies on long-term practice for execution. Your short-term memory needs to register all the different sounds in a song, all the changes in rhythm, all the highs and lows, all the build-ups and releases. Learn to remember and recall them by listening once. That will prove you can think about those while improvising. Listen to what others are playing in your musical sequence and respond to that.

- Learn building blocks like chord arrangements and famous sequences: Your musical improvisation aquarium needs more fish. Practice and rehearse them as much as you can, so you can deploy them while free-styling.

- Swap elements: Using the basic building blocks, swap a few notes or a few chords. Or mix up the rhythm. For sound, small changes can make a huge difference to how the music feels. Replace an A with a C. Replace a shuffle with a 4/4. Swap a chord in a sequence with another small sequence.

- Learn from variety: Musical learning is very example-driven. So, learn as many examples as you can and implement them in ways you don’t typically hear them. Then, make them make sense using other techniques.

Cooking Improvisation (Home kitchen)

- Learn what ingredients go together: Understand the relationship between salt and sugar and how they balance out. Learn how lemon adds tang or curry leaves or MSG to change the flavor. Haaiiiyaaaa!!!

- Learn Basic Techniques: Get some experience in microwaving, sauteeing, frying, shallow frying, making masalas, thickening gravies, etc. Once they feel intuitive, try swapping ingredients or your primary veggie or meat.

- Use what you have: Your first improvisation in the kitchen should be with things you already own. Work within limits.

- Taste and use feedback: Since cooking is a slow process, keep monitoring what you do and modify it. You don’t have to have a set goal. Think – how can I make this work?

Acting Improvisation (Improv or Stand Up)

- Yes, And…: The most common rule of improv acting is to accept what another actor presents (“Yes,”) and then add to it (“And…”). For example, Actor 1 says, let us go on a voyage across the Pacific. Actor 2 says, “Yes. And we will use this chair as a throne for our captain.”

- Look around: Improv is paying attention to what you see around you and using it in any make-believe way. A stick is a sword. A chair is a throne. A stage is a cockpit. A person in front of you is your future self with plastic surgery because you became famous, and he can’t have your face anymore.

- Be basic: You don’t have to go full-fledged right away. Stay unhinged, but practice in simple ways. Build one small idea over another.

- Empathy & role-play: Use what you’ve seen in media and what others have done in your life. Mimic them. Derivce from them. Use your empathy to be in their shoes and commit to that role-play.

Forced improvisation: Limits help people get creative.

Restrictions can force the brain[4] to see resources (available options) from new perspectives. Just because you won’t have unlimited time, space, money, tools, and energy, you’ll need to think differently about what you have to reach a certain goal. To cook a good meal at home, you are limited by what you have or quickly buy. Improvisation triggers when you find ways to make do with the ingredients you have. Like swapping the meat for potatoes, swapping spices for sauces, pan frying instead of deep frying, etc. If you go to a supermarket with virtually unlimited options and a large budget, you get unlimited options for your meals, and that is the problem – you’ll take a non-improvised recipe approach.

Having modest constraints can lead to emergent creativity (accidental creativity) and deliberate creativity. Since reality has limits, knowing your constraints helps during creativity at work. The problem-space theory of creativity and constraint[5] says a healthy balance of constraints and ambiguity in your problem statement can be good for creativity. But, having too many or too few options/resources for a very specific problem can lead to creative “dead zones” – aka roadblocks.

Practicing and preparing for improv

Improvisation is practiced by improvising, but not directly. It starts with learning a wide range of things. Learning by exposure to a wide variety of examples, tricks, concepts, etc., allows the brain to extrapolate and tackle new problems more easily. In a way, you are practicing improvisation by using the various things you’ve previously learned. That variety lets you plan your steps ahead because variety creates a bigger knowledge base.

Accidental creativity in improvisation

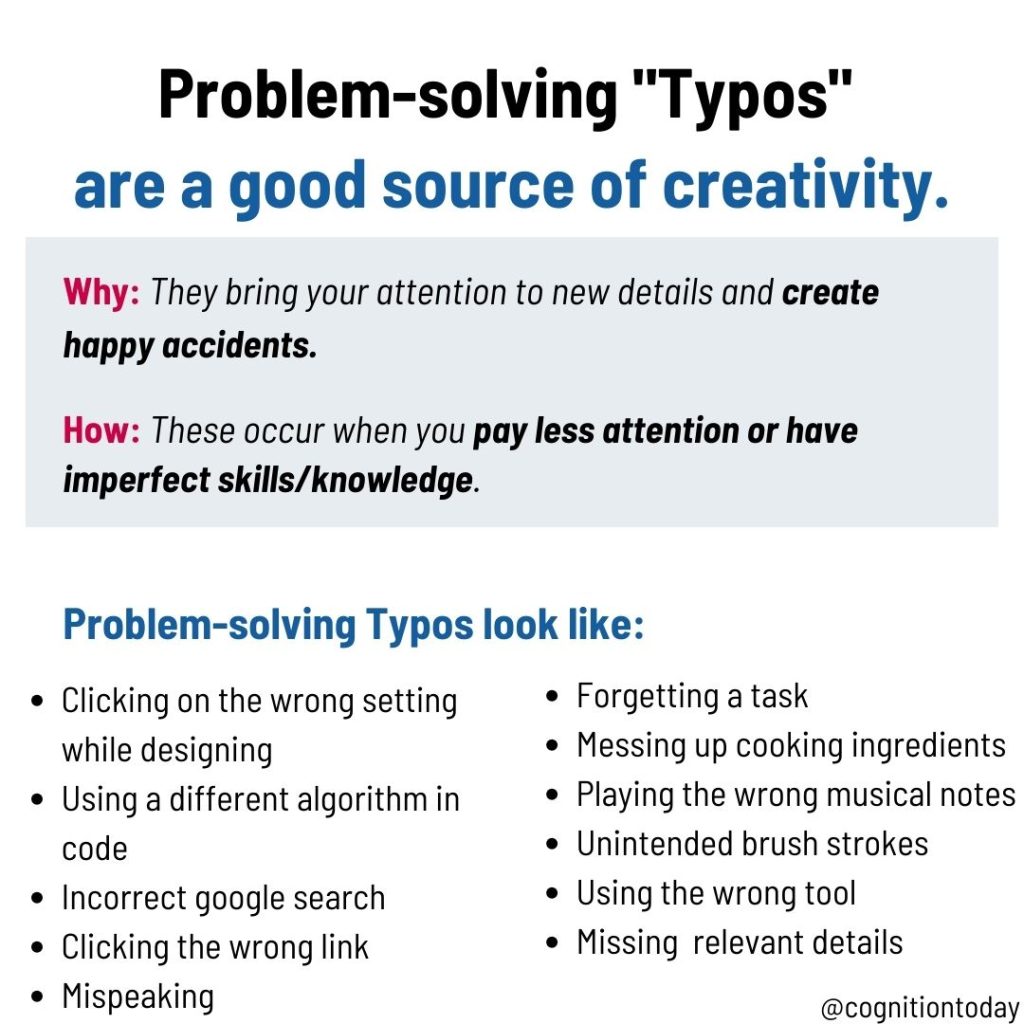

While playing the guitar blindfolded, I’ve often seen some “wrong” notes making sounds from somewhere on the guitar. Some of those wrong notes end up sounding great. I then have to reverse-engineer to find out what those notes are. These accidents are what I call “mental typos” or “problem-solving typos,” like an attention-grabbing text typo while chatting. They are happy accidents. Improvisation is about letting these happy accidents emerge. For more happy accidents, chaos helps. They are technically called “chance configurations.”

Improv creates hope and confidence

Waypower hope

If you look at research on the concept of hope, researchers have observed 2 independent paths to hope. The first is willpower hope – what sort of energy you can give to achieve something and how much you are willing to resist the difficulties to win. This is the classic form of hope. The more practical form of hope is called “waypower hope,” which is all about problem-solving. Specifically, improvising. Waypower hope is the hope we get from realizing that we have a practical solution to overcome some problem. Money found in a pocket can create it. A random phone call you make can create it. Anything improvised can create it. All you need for that is a sign that shows a practical solution to your problem.

Confidence

Confidence is your belief in your ability to succeed. In most cases, being well-planned can give you enough experience of success to feel confident. But what happens when you can’t plan or are put in a situation where you have to make tough decisions and perform? Researchers tested this[6] with English as a second language teachers and found that improvising improved their confidence in speaking. Improvising successfully means you have seen proof of your capacity to succeed without extensive planning. Over time, the more you can improvise, the more you feel you can handle things on the go.

P.S., This article is improvised from 1 section from another article I wrote on creativity.

Sources

[2]: https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/yotam_ottolenghi_606729

[3]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187118712100208X

[4]: https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/5/767/1855952

[5]: https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.119

[6]: https://nordopen.nord.no/nord-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2685695/Zondag.pdf?sequence=4

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.