Yes, critical thinking is hard to define and a constant victim of debate. Educators and experts have attempted to define it in separate contexts. I’ll give some examples.

But first, do you want to know if you can think critically? Take the test below.

Critical thinking test

Instruction: Give precise answers in the form of single words or numbers.

Format: 9 questions

Wasn’t that fun! Share it and test your friends 🙂 It’s not as easy as it appears. Many experts across all domains fail at this, often when they are tired or on autopilot.

Now, let’s look at the psychology of critical thinking. What exactly is it?

Foundations of critical thinking

Bloom’s taxonomy

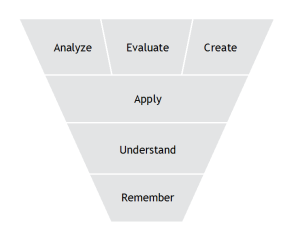

The famous Bloom’s taxonomy, widely used as an educational guideline, has 6 layers of cognitive development that education must facilitate. The 4th and 5th layers approximate critical thinking. They are “analyzing” and “evaluate.” Both layers are also commonly put under the umbrella of Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) because they are effortful ways to process information. Evaluation is mostly about passing judgment on information. Analyzing is mostly about computing and comparing ideas. Both are about taking some information and processing it in a way that simplifies a problem and lets one create a solution. But this isn’t enough. Maybe in its best version, it involves critical thinking. But its weaker version is just deliberate thinking, which may not be critical. For example, a teacher may ask students to evaluate patterns across different mammals near human civilization (like the females produce milk, many mammals are eaten, etc.). This involves deliberate thinking but doesn’t invoke critical thinking. To make this a critical thinking task, a teacher can ask students to estimate characteristics humans do not have but are typical of mammals. This would change the subject of the activities to talking about technology and controlling the environment instead of “fetching” details about mammals.

Remember: Recall

Understand: Conceptualize

Apply: Solve familiar problems

Analyze: Comparing and contrasting concepts, formulating a problem.

Evaluate: Passing judgment on information, questioning it

Create: Formulating complex problems and finding solutions to novel problems

Philosophy & Logic

Philosophy looks at critical thinking mostly from the logical perspective, where rules govern the correctness of an idea or flow of thought. In logic, critical thinking is about the premise, assumptions, internal consistency, and inference. Logic looks at critical thinking by asking the question – If the premise is true, does your conclusion correctly originate from the premise? Are you assuming something? Let’s explore all of it.

- Premise: It is a statement of information. It may or may not be true. Critical thinking means questioning it’s true-ness.

- Assumption: It is information not explicitly given to you, but you’ve considered it as background information or context to help you process the problem and solution. Critical thinking means spotting assumptions.

- Internal consistency: It is the correctness of logic within a premise. Critical thinking is observing if an argument or idea is internally consistent. TOMM example: I was using AI to make a thumbnail for this article, and it gave me an image of a skyscraper office with a transparent glass room with 2 suns shining through the panes. Makes no sense on earth, right? The image isn’t internally consistent with the earth’s reality. Yes, this could be another planet. But I don’t have alien friends to DM me this image.

- Conclusion: It is derived from the premise as a logical statement or solution. Critical thinking means working out if your conclusion is correct as per the details in the premise.

In other cases, asking questions is treated as the first step to critical thinking. The common advice is to ask and verify things by asking How, Why, When, What, Where, and Who.

Related: The science of good observation skills

System 1 and System 2 thinking

Cognitive psychologists look at critical thinking mostly from a system 1 (intuitive) and system 2 (analytical) thinking perspective. A popular way to understand critical thinking is to measure how people can suppress system 1 thinking, which is fast and automatic, and use system 2, which is slow and deliberate. In shifting from system 1 to system 2, a person re-evaluates the information and draws conclusions. A person might instinctively stereotype a stranger (System 1) based on looks but then use critical thinking to challenge and reassess these initial judgments (System 2).

System 1 thinking is intuitive + feeling. System 2 thinking is deliberate and analytical. When a question has a wrong answer using system 1, finding the right answer using system 2 is a test of critical thinking.

The famous cognitive reflection test (whose questions I’ve added to this quiz) pits system 1 against system 2, and it defines critical thinking as the ability to suppress system 1 thoughts and override them with system 2 thoughts.

Common sense

Common sense cares more about having the right logic (not some logic), assumptions, and context. It is a simplified version of critical thinking. It is having an economical and contextually correct thought. I’ll show you how common sense is contextual.

During my early guitar-playing days, I watched videos of people playing very fast. They attracted many naysayers because it was unbelievably fast so they assumed the videos were sped up. So the guitarists started adding a clock in the background. A lot has happened since then. Almost 20 years later, guitarists’ skills have reached new heights. Many of the new young adults playing guitar who naturally believed guitarists have speed game wonder on Instagram comments – why is there a clock in every video? And some old-timer is always there to insult, “RIP Gen Z commenters, you lack common sense. DUH, it’s to show the video is not sped up.” Common sense comes from context and finding a simple connection between different things you observe.

Context

Just thinking hard isn’t enough. Humans require context for thinking accurately. We fail miserably at logic when we treat it like logic, but rarely make mistakes when that logic is in a context. I explore that in depth here. Context always matters in the real world.

For example, let’s say A > B > C. (A is greater than B and B is greater than C)

D may or may not be greater than B. Is D smaller than A?

Compute that. Or, compute it with the context below.

A human (A) is larger than a monkey (B) which is larger than an amoeba (C). Sharks (D) may or may not be larger than a monkey (B). Are humans (A) larger than sharks (D)? The question can’t be answered with certainty because some humans could be smaller than a shark and some could be larger.

Answering the second version is easier for most because it allows people to imagine the problem in a context. The logical format is very easy to solve, but it is symbolic and much harder to imagine.

Relevant information processing

Worked-out problems are easy to think about, so practice can make perfect. Like problems in a math exam or algorithmic thinking. If you solve enough, you know how to solve similar new ones. It becomes easier to spot what you know and what you don’t know. But that is because the practice material is a set of well-defined problems. This is not the case in the real world. IRL problems are ill-defined. And most people, including whole organizations, have to first formulate the problem they need to solve. So, critical thinking begins first by identifying relevant information and ignoring irrelevant information. This is the classic idea of finding the signal in the noise.

Every scenario, question, or problem has relevant information called “the signal” and irrelevant information called “the noise.” A critical thinker’s job is to judge the scenario, and classify information as signal vs. noise, and then use the signal to think clearly. The irrelevant information can have a strong influence on us, so the thinker has to block it out. For example, in war scenarios, the weather conditions that suit a certain people can create an advantage against invaders. In this case, the weather condition is a part of the signal. The invader’s war funding status might be the noise. What good is the battle equipment budget in determining the outcome if it can’t even be used in a certain climate?

But, identifying the signal from the noise is not enough either.

Mental Sets & Past Experience

Humans are not computers that reboot and start on a clean slate. We exclusively rely on memory and past learning. There is a carry-over effect from what we are used to. That means if we solve one type of problem for days, we will tend to solve another new problem the same way. In the same way, if we only know how to use a hammer, everything will feel like a nail.

But the story doesn’t end there either. I’m not being dramatic, but critical thinking has so much more to it. We come with a “mental set[1]“. A mental set describes how our approach to a previous problem can shape our approach to the next (similar to priming, but this is more about learning than temporary influence). For example, if you’ve been working on statistical problems all day, you might initially approach a creative task by seeking patterns and data, even when this approach isn’t suitable. Recognizing and adjusting our mental set is a key aspect of critical thinking. We apply an approach from our previous task to another task. I’ll give you another example. If you are doing a sales job dealing with people and understanding social details like what people say, how they dress, etc., and then you immediately watch a TV show, your focus will go to the social details of the characters in it. This means the mental set from your job continued for your TV sesh.

Even experts who have solved problems a certain way for decades will fail to see a simpler solution that you can find with critical thinking. This is the infamous expert paradox called the Einstellung effect.

Cognitive abilities

The brain didn’t come equipped with software. It came equipped with a few core abilities that let us build the DIY personal software to tackle new problems. They are commonly called “executive functions,” and 3 of them are most relevant for critical thinking.

- Attention: The information that gets prioritized by the brain. It’s deliberate (focus) and automatic (distraction).

- Cognitive flexibility: It manages our capacity to switch contexts, jump between ideas, and return to something we’ve thought about. It’s the executive person who juggles between different brain circuits and ideas.

- Inhibitory control: Our brain knows what flow of thought to stop or continue. Response inhibition is the capacity to stop an idea and revisit it, a very critical component of critical thinking.

Core cognitive functions are applied to details given in a situation and what you have learned. The whole thinking becomes thinking about thinking, called “Meta-cognition.” So critical thinking is a metacognitive skill. It’s a slower process where speed is de-prioritized than detailed analysis. It’s effortful and mentally exhausting, so staying critical for hours and days is hard. This is exactly when being a practiced expert helps. The critical thinking elements in a particular skill set are repeated so many times that they are like a mental habit. There is a clear sign from a brain-imaging study[2]. As a skill is practiced more and more, it stops relying on executive functions and uses long-term memory. Conversely, new problems demand the use of executive functions – attention, memory, and decision-making – which are needed for critical thinking instead of long-term memory. This is why we observe it is easier to think critically about unfamiliar problems.

The biggest threats to critical thinking are cognitive biases. They are thinking tendencies that use very little information to draw conclusions at a fast rate. They are most activated when we mundanely move through life as we make fast decisions. Here are some examples and how you can counter them. But I’ll cover 3 cognitive bias threats I feel are the most significant.

- Belief bias: The belief bias is best summarized as “If it feels right, it must be right.” People will buy into any wrong logic if it superficially sounds believable. For example, if someone tells you fish belong in water, so eating fish and milk together is bad because their bodies are not adapted for milk, you might believe it. After all, the fish didn’t evolve in milk. So maybe it’s true. Critical thinking is asking – What does the fish’s habitat have anything to do with our body’s ability to digest the combination?

- Confirmation bias: Confirmation bias is as it sounds – we seek information that confirms what we know, and we ignore information that doesn’t fit into our preconceived notions. For example, if you google “Why is meat bad for health?” you’ll get answers confirming it’s bad. But if you google “Why is meat good for health?” you’ll still get answers confirming it is good.

- Anchoring: Anchoring is having some reference point that guides our estimations based on that anchor. For example, if the average coffee costs $5, we believe $6 is ok but $9 is too much. Our perception is anchored to $5. But if the anchor were $10, we’d be fine with $9.

Related: 7 Attention biases that are killing your observation skills

Conclusion

So, how do we combine these core ideas into the concept of critical thinking?

Ok. I’ll define it this way.

Critical thinking is a purposeful way to think about details and suppress past/immediate influences that may misdirect us. The tools to achieve this are: questioning assumptions, isolating details of a problem, and taking a step back from “what feels right”. It almost always requires challenging some details and/or challenging your own perception of a problem.

That sums up knowing what critical thinking is. Regarding improving it, I recommend a ground-up approach through everyday activities listed here. If you only solve critical thinking problems, you’ll benefit, but you’ll also succumb to the mental set problem.

P.S. The questions are from the cognitive reflections test, a test of critical thinking that does not require domain knowledge and some trick questions I found on Instagram. I do not know the source of some questions. But, each question is derived from 1 or more of the theories that explain critical thinking.

Sources

[2]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16242923/

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.