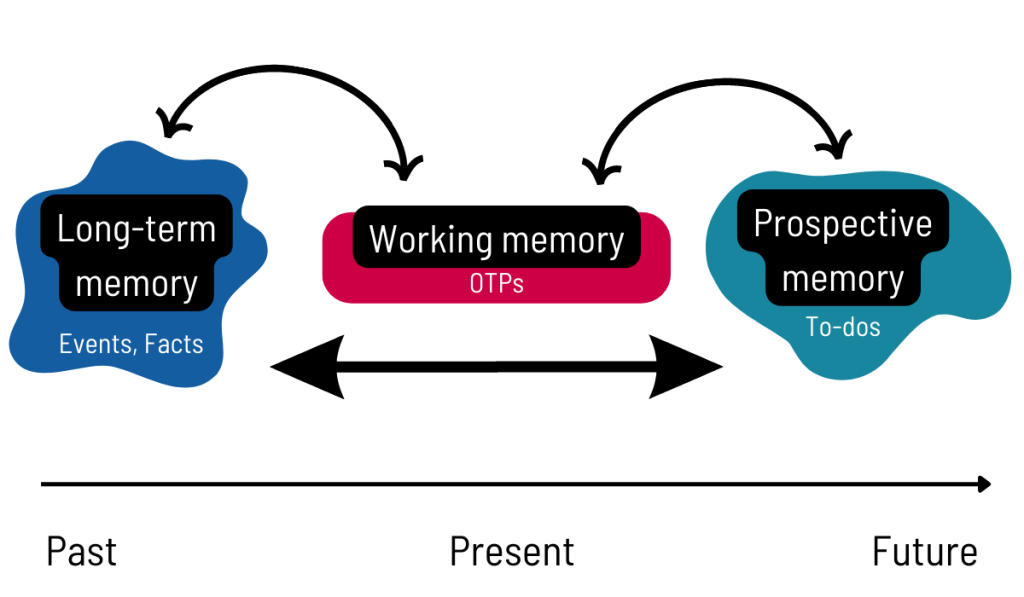

When we think of memory, we usually think of “retrospective” memory which is the memory of past events/facts, or “working” memory which is the memory of information you are currently holding in your mind. But, apart from these 2, a 3rd type of memory called “prospective memory” exists. It is extremely vital to everyday functioning, planning, productivity, and learning, with bad consequences when it fails. It is – remembering to do something in the future.

What is prospective memory?

Psychologists describe Prospective Memory as “remembering to remember and act,” “future memory,” or “forming an intention to remember and act.” It is a mental reminder like carrying out an intended action, to-do items, making mental notes about future actions, and self-instructions like “remember this, it is important.” If remembering is called recall, prospective memory is delayed recall. 50-80% of everyday memory problems[1] are likely to be prospective memory problems, with one of the biggest concerns being – forgetting to do something on time. Forgetting to act on what you’ve planned or forgetting what you should’ve remembered can have bad consequences – you may leave the iron plugged in and cause a fire, you may forget to send memes to your bae and risk making them feel ignored, or you may forget to take birth control and risk pregnancy.

Prospective memory emphasizes the intention of memory and not just the memory. For example, telling yourself to remember to call a friend before 10 pm occurs via prospective memory. This is an intention to make the call. When you forget to call your friend, your prospective memory most likely fails.

Researchers define[2] prospective memory (PM) as the ability to plan, retain, and recall an intention as planned. The intention of certain details is tagged with an “importance” level which helps us remember the detail and execute the intention in the future. We typically recall information that has a high importance tag and forget the low importance bits. However, factors like cognitive load (how much work your brain is currently doing), interference[3] (other things competing for brain processing), motivation (incentives, reward, positive feeling, etc. related to remembering), and distractions affect whether the intention is remembered or not.

To succeed with PM, you sometimes have to interrupt another activity. For example, you may have an important call to make (the intention), but it slips your mind because you are working on a report which needs your complete attention, or you get engrossed in a TV show and zone out for a few hours. Similarly, if your doctor instructs you to take a pill at specific times of the day, the reward of pain relief might help you remember the instruction and execute it with discipline.

PM has 2 parts. A small retrospective (past) part that tells you “what” and “when” you have to remember, and a prospective (future) part that tells you that “you have to” remember something in the future.

Prospective memory examples in everyday life

- Remembering to take medicines before bedtime

- Planning to charge your phone while you go for a shower

- Remembering what a teacher said about what’s important for the exam

- Remembering what to bring up in conversation during weekly calls/meets

Common failures of prospective memory

- Forgetting to send something to someone when you say you’ll send it

- Forgetting a medicine dose

- Forgetting instructions left by a partner/friend/peer/boss/authority

- Forgetting to turn off the gas or water heater

With the risk of overgeneralizing, being a good planner likely means your PM is good. And being forgetful or absent-minded likely means your PM is failing.

Types of prospective memory

We use 3 types of prospective memory[4]: time-based prospective memory, action-based prospective memory, and event-based prospective memory.

- Time-based prospective memory is when you want to remember a task before a deadline. For example, remembering to send an email before 6 pm next Friday.

- Action-based prospective memory is reminding yourself to perform a task with no clear time constraint. For example, remembering to buy a particular ice cream the next time you visit that location.

- Event-based prospective memory is remembering that a specific event will occur in the future that will guide your behavior or decisions. For example, remembering there is a blood moon in a few days would be relevant to a date you are planning.

We need all 3 types of prospective memory because many prospective thoughts are not relevant at the moment but gain significance later at a particular time, location, or context. For example,

-you are away from the laptop but have something to change in your work

-you’ve thought of something to say, but you have to do it 1 week later in a meeting

-you have things to buy, which you need to plan for the weekend

PM can be either immediate-execute or delayed-execute[5], and both affect daily functioning. Immediate-execute is when you have to do something the moment something else occurs. Like taking out the trash when it’s 9 am. Delayed-execute is when you have to do something later. Like returning to the kitchen to remove the lid from a cooking pot after 10 mins of heating your rice.

Benefits of having a good prospective memory

- Perhaps the most valuable use of prospective memory is following instructions and using them appropriately. When someone instructs you “remember to turn off the lights before leaving,” you form the intention to do so and succeed only when you remember it while leaving.

- Knowing what you have to do can help with all sorts of planning and organizing.

- You remember social details like people’s names, jobs, last conversations, relevant details, etc., which improves networking and relationships.

- Prospective memory about all developments in a day can help you manage priorities and create agendas as a manager or team lead.

- You can experience relief from a sense of “completion” when you tackle everything you have to do.

- Unintentional procrastination due to casual forgetting reduces, which benefits us in 2 ways: reduced anxiety/stress and finishing work.

- Instead of flooding your notes with lists that can get overwhelming, prospective memory helps by offloading some of the work to memory and some of it to written to-dos.

- When prospective memory stays in the brain, the default mode network (idle brain processing) and deep sleep operate on it by linking it to other memories, re-organizing it, re-processing it, etc., which can lead to creative insights.

- Prospective thinking is “activating” for productivity. It resolves the question “what did I have to do?” many times!

What affects it?

Age and genetics are natural reasons that affect PM. As age increases[6], people tend to lose prospective memory and fail to remember something they’ve already declared important. Generally, PM improves from childhood to adulthood[7] and then declines till death[8]. While older people have more retrospective memory complaints, younger people have prospective memory complaints. Older people can acquire strategies to improve prospective memory and offset the decline. Lifestyle factors like smoking[9], alcohol (moderate[10] and extreme[11]), sleep deprivation[12], marijuana[13], and drugs (MDMA[14]) affect it too. Diseases like Alzheimer’s, dementias[15], and mental health disorders like depression and post-traumatic-stress-disorder[16] (PTSD) worsen overall memory, including prospective memory. Those with mild cognitive impairment[17] and brain fog frequently have PM issues. These tips might help.

Motivation also affects prospective memory. When there are rewards to remembering something in the future and executing an intention, rewards in the sense of gaining something or avoiding a loss can motivate us to remember. So generally, awareness of the consequences of successfully remembering to remember helps improve PM.

Finally, cognitive engagement with other tasks may or may not block PM. If that activity has your complete attention, PM might fail.

What triggers prospective memory?

Research points to a few possibilities[18]:

- Something in your environment triggers the memory. For example, a random conversation with friends might trigger the thought of doing something. If they talk about renting a house, you might remember you have to pay the rent and manage your weekend expenses.

- It spontaneously emerges as a part of many other random thoughts that pop into the mind. Sometimes, you might remember an intention to do something (like ordering from Amazon) when you are humming a song while cleaning.

- Your brain constantly monitors that prospective memory (or intention) until it is remembered. Other times, you might remember the names of people you just met at a gathering because you’ve been periodically remembering them to reinforce your memory.

In short, the prospective memory will:

- you’ll remember something because you are cued to remember it

- randomly pop in your mind

- information will strengthen because it’s remembered multiple times

Prospective memory is a form of metamemory; it’s an anchor to a thought. Remembering the anchor kickstarts the thought again. Metamemory is a layer of memory on top of actual memories that acts as a quick access point for the memory. For example, you can confidently say you know a song without fully remembering it. You are just aware that you know it. In the simplest sense: PM creates a stimulus-response pair, where the stimulus is the anchor/trigger/cue or partial detail or the intention and response is the entire combination of the memory and its related action.

How to build prospective memory

Prospective memory is built indirectly as a meta-skill – a byproduct skill from executing other skills. The core skill here is spacing – information remembered a few times with gaps is recalled better than information reviewed just once. The production effect also builds this skill – knowledge produced by the brain on purpose is remembered better than information just passively absorbed. On top of this, the brain uses different systems for recall and recognition, so practicing recall is as important as paying attention to something to improve memory. Educators call this retrieval practice, which is practicing the ability to access memory. Generally, paying deep attention equates to giving it importance and kickstarts “elaborative rehearsal,” which is deeper memory processing. This deeper processing links it to other memories and contexts and increases the significance level of that memory. These are active behaviors that can improve the meta-skill of prospective memory.

- verbally say what you need to remember in X time

- tell someone about it

- pay attention to the context in which you remembered it

- try to remember what you planned to remember during the shower or commute

- link your prospective memory to a goal

- note it down in an app or a self-Whatsapp group

- give yourself specific reminders like “remember this while doing X” and “remember this before bedtime”

- attach an emotion to it by thinking about it more; this gives it more importance

- look around carefully for hints, indicators, or locations that might trigger a memory

- associate avoiding a loss or receiving a gain related to remembering the prospective memory

- think about the events of your day and your plans for the next day before bedtime; these might trigger PM

Storing information on the phone or in a talking context like WhatsApp increases access to that memory because we often remember where information is more than what it is. This helps us navigate to the information. If we know where to find it, we can practice finding it and learn to trace that path mentally, which can lead us to the important details.

Even giving ourselves strict reminders is useful because those reminders act as additional cues to remember. The more you use prospective memory, the easier it gets. More instances of remembering the prospective detail strengthen access to that detail. The more you do this, the more you train your ability to reliably remember details without cues, notes, or calendar prompts. Essentially, prospective memory evolves and flexes like a muscle.

Avoiding a loss and approaching a gain motivates people. So highlighting this can make the intention in your PM stronger. For example, remembering to take medicine on time can be linked to pain avoidance, which is naturally motivating. Similarly, remembering to drop your laundry on the way to work and not wait till later can be associated with a gain like saving time.

And as a safe practice to ensure overall memory is good, take care of physical and mental health, including nutrition, sleep, stress, mental engagement, exercise, and coping mechanisms.

Sources

[2]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00657/full

[3]: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.139.7033&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[4]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00657/full

[5]: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.139.7033&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[6]: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0882-7974.19.1.27

[7]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2856082/

[8]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18608976/

[9]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20800391/

[10]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hup.1194

[11]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-009-1546-z

[12]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09658211.2013.812220

[13]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0269881109106909

[14]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-007-0859-z

[15]: https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad150871

[16]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13421-023-01400-y

[17]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11065-011-9172-z

[18]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00382.x

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.