Some people like reading content. Some people like watching videos. Some people like listening to audio podcasts. For decades, this observation has sustained a psychological myth; I examine how much of it is a myth.

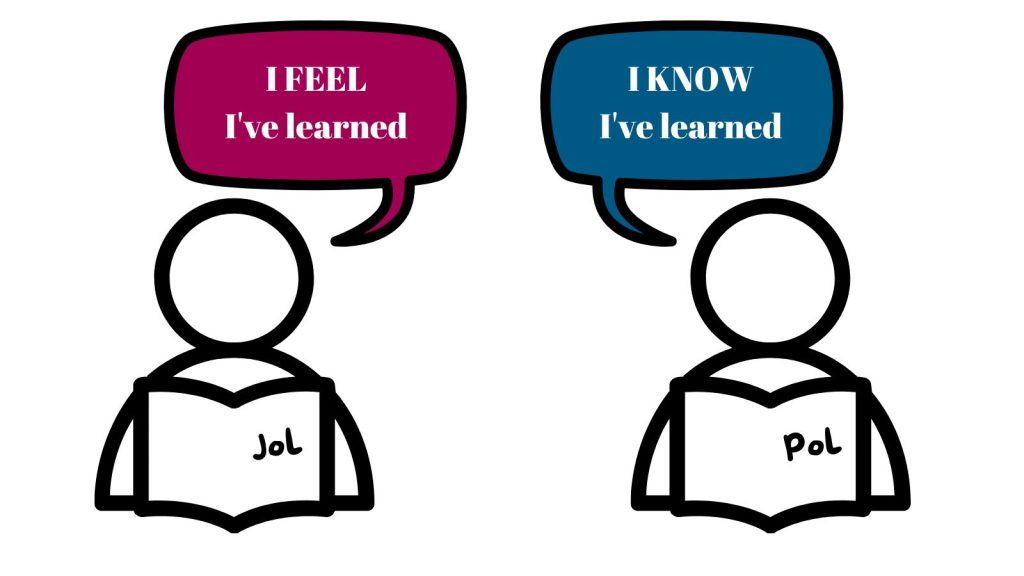

So… if you like one sensory format, it must mean you have a unique preference, right? Yes. And if you prefer it, you will grasp the content in your preferred format better, right? While you might say “yes,” research says otherwise. We must differentiate between Judgments of Learning and Proof of Learning to find the real facts hidden within the fiction.

Learning styles – the concept

A common notion is that people are auditory, visual, or kinesthetic learners – the 3 modes of learning are called “learning styles.” Many students believe they are auditory learners – better learning through talking or audiobooks, or visual learners – better learning through videos and text, or kinesthetic learners – better learning through experiences or play.

The most popular version of this is called VARK, which categorizes people as visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic learners. Charles C. Bonwell and Neil Fleming spearheaded the idea in the early 1990s and created the VARK system, quite successfully. But let’s look deeper.

The VARK idea is intuitive for many, but it doesn’t mean they learn better through their preferred learning style. They feel they learn better because it’s their preferred format, so it influences something called “Judgments of learning.” That differs from “learning,” which I prefer to call “Proof of learning.”

You might be wondering if there is any real difference between the 2. Judgments of learning are based on emotions. And learning is based on some proof that you have acquired or implemented some knowledge.

In everyday conversation, the idea of learning styles is simple – if you like videos, watch videos. If you like reading, read. If you like hands-on experience, get hands-on experience. But, education, EdTech companies, and many students and teachers take it too far by prescribing students content in their preferred sensory format. This creates the illusion of improving learning but just improves judgments of learning.

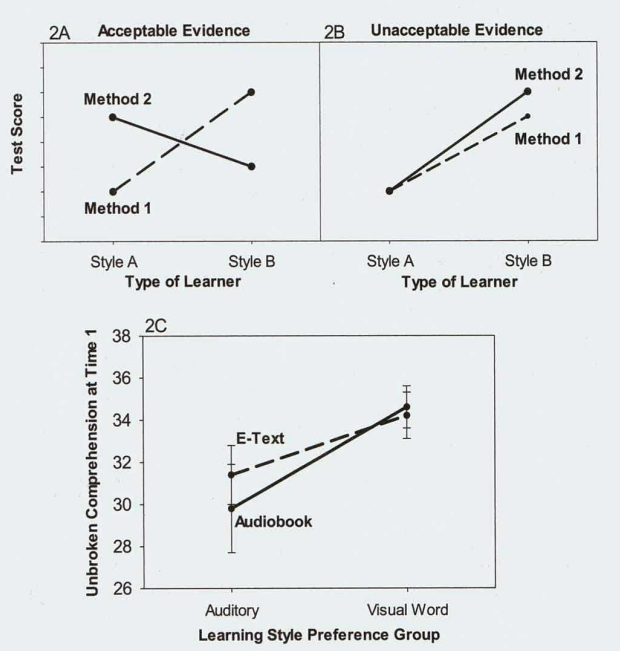

Experimental psychology has tested this for 3 decades – does matching your preferred learning style to content in that style help? It’s so popular that it has a name – the meshing hypothesis.

The meshing hypothesis – proof it’s a myth

The meshing hypothesis[1], which states that auditory learners learn better through auditory content or visual learners learn better through visual content, is not supported by evidence. And by extension, tailoring educational instruction to match a learner’s learning style is largely a wasted effort.

In the study linked above, college-educated participants classified as auditory or visual learners based on a standard learning styles test were randomly given an e-book or audio-book style non-fiction content to study. So, 4 groups were formed: auditory learners who got an e-book, auditory learners who got an audiobook, visual learners who got an e-book, and visual learners who got an audiobook. Their comprehension was tested immediately and 2 weeks later. As expected – no group showed any statistically significant difference in their performance. They all performed equally well immediately and also 2 weeks later, although the performance dropped roughly 10% for all groups when checked 2 weeks later. Matching the learning style to the mode of instruction made no difference to anything. They did not perform at the score “ceiling,” nor was the test too difficult – all 4 groups averaged around 30 out of 48 points on the test.

Research shows learning styles do not have a meaningful impact on learning. According to many studies, the concept of learning styles is an invalid way[2]to describe how most people learn, how most people prefer to learn, and how effective or persuasive the learning material is. While students have their preferred formats for learning[3], their preference does not affect how effective the learning material is. The most accepted explanation for this is that students’ beliefs about their learning style[4] affect their “judgments of learning” more than the actual objective learning. Judgments of learning (feeling good or bad about the quality of learning) affect confidence, which could influence test scores.

Frank Coffield, who authored a 182-page report on learning styles[5], says researchers have forever studied learning orientations as dichotomies – auditory vs. visual, abstract vs. concrete learners, deep processors vs. surface learners, etc. 30 such dichotomies have been found in the research. So, at the very least, 230 combinations of those dichotomies can apply to every learning, which is about 1 billion different combinations – aka 1 billion “learning styles.” If 1 billion learning styles exist, that categorization is meaningless.

Judgment of learning (JoL) is quite important in the broad sense. JoL is a metacognitive process – it is literally evaluating how well we have learned using feelings about the learning experience. We tend to conclude – if it feels like real learning, it must be real learning. 5 experiments studied the effect of JoLs on reading comprehension[6] and found that a positive JoL does not enhance comprehension by default. But if students are asked to make JoL based on remembering what they have learned, there is a direct improvement in their score. Technically, this is a benefit coming from “retrieval practice” – attempting to remember something as proof of learning. So by passing a JoL by actually remembering, JoL becomes PoL – Proof of Learning.

Positive JoLs improve learning motivation[7], confidence, and eventual scores. It also reduces anxiety. But having too positive a JoL when academic skill is very high can also turn into overconfidence that later harms test performance. For highly competent students, who also have a very positive JoL, their goals should ideally reflect mastering a topic and pushing specific boundaries of learning to NOT lose to overconfidence.

Why the myth became immortal

There are 3 additional reasons apart from judgments of learning that explain why we are still obsessed with learning styles. First, our analysis of the world depends on our decision-making errors and judgment errors. Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel prize for showing this mathematically. He and his colleague Amos Tversky describe something called the representativeness heuristic. It says we tend to believe some things belong together better because one thing represents a core component of another thing. The logic of thinking someone good at science should be a scientist and someone good at writing should take arts is the representativeness heuristic at play.

Since we have limited senses through which we consume content, we tend to apply the representativeness heuristic to it and believe matching the sense to the content format should make sense.

Second, a far simpler secondary reason is – we love organizing information and finding patterns. It’s probably the only way we assign meaning to something, and it gives us a sense of control over that information. Because the idea of learning is so complex and vast, learning styles have become an elegant (but flawed) way to describe a whole educational system in a simple pattern.

And third, if it is repeated a lot, it feels true. The aptly named – illusory truth effect[8]. A technique used in building narratives, gaslighting, manipulation, propaganda, etc. If something is repeated over and over again for decades, we assume it’s true. The explanation researchers offer is that familiar ideas are processed easily, and ease of processing is equated to truthfulness.

So categorizing people with their learning style now meets 4 criteria for a “sticky” learning theory:

- It creates judgments of learning (essentially a feeling).

- It uses the representativeness heuristic (it feels correct).

- It reduces ambiguity in a complex concept called “learning”.

- Repeating it makes it feel true.

Considering these 4 problems, we see evidence of companies thriving on the concept, educators swearing by it, young intelligent learners “overusing” their introspection with a confirmation bias, etc., making the myth stick around in society.

If it feels like it works, it must be true right? It’s not that simple!

Takeaway

The meshing hypothesis – matching learning style to content formats – may not help students in actual learning. But a holistic sense of learning requires proof of learning and the feeling of learning. Emotions play a role and having a likeable format or preferred format does affect the motivation to learn. So, while learning styles are more of an illusion and not worthy of being a firm theory of learning, it is valuable in some significant but minor sense – for the feeling it creates while learning.

For teachers

Resources can be better spent on teaching students with fun and engagement so they get a positive judgment of learning, instead of spending on learning styles custom content and apps. Fun, sensory engagement, liveliness, and curiosity improve learning by default, and that makes students’ brains welcome new information more easily.

Action: Use a brain-based system that covers everything by aligning with how the brain works and where individual differences emerge from, instead of crudely classifying students.

For students

Learn in any way you like, but don’t limit yourself to beliefs like you must learn only with your learning style. That would be self-sabotage. Combination learning is far more effective. Read and Listen and Watch and Experience your learning materials.

Action: Use specific and obvious studying best practices and avoid obvious bad habits.

Sources

[2]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360131516302482

[3]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0098628315589505

[4]: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjop.12214

[5]: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A13692?ref=brainscape-academy

[6]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-020-09556-8

[7]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10212-010-0030-9

[8]: https://cognitiveresearchjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41235-021-00301-5

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.