Back in 1969, a guy called Laurence Peter[1] made a shrewd observation and published a book on it – The Peter Principle.

If you are someone’s boss, you probably know this. You can skip ahead to the part where I discuss how to counter the Peter Principle.

I’m certain everyone has a friend who complains about how everyone sucks at their job and how incompetent they are.

What if I tell you that your friend is not exaggerating? There really is a reason why you feel your colleagues/co-workers/bosses suck at work and don’t deserve their position & pay.

Don’t worry; not every employee is incompetent. I’m not saying YOU are incompetent.

So what is the Peter Principle?

L. Peter observed that people who excel at work are promoted, and a series of these promotions bring them to a point where they are incompetent. With every promotion, you are closer to newer and more complex job needs. This incrementally makes you worse at your job to the point of incompetency.

This is when your juniors and freshers will think – you suck; how the hell were you promoted?

The Peter Principle: In a Hierarchy Every Employee Tends to Rise to His Level of Incompetence.

Another way to interpret the Peter principle is that employees start performing worse after a promotion. There is a disparity between a job’s skill requirement and your actual skill set. The requirement is higher.

What Peter observed was quite intuitive. It made sense to employees and bosses all over the world, making his book a best seller. A million copies and was a best-seller in the US for 33 weeks. Here is the book. You can click the link to buy it.

The Peter Principle: Why things always go wrong

Affiliate link for purchase[3]

Is this observation profound? What does the research say?

Mechanisms Behind The Peter Principle

Researchers at the University of Minnesota and Yale University analyzed data from 214 firms[4] and found that promotion decisions are based on an employee’s current performance level. However, the current/latest performance level does not correctly predict performance after a promotion.

Many promotions involve moving away from a technical job profile and adapting to a managerial job profile. Management requires managerial skills – such as accountability, problem-solving in team conflicts, decision-making after technical counsel, etc. Technical jobs don’t always involve these skills. There is incongruence between one’s current and future job profiles if this happens.

It makes sense that managerial skills predict manager-level performance. And yet, companies spend resources to award promotions based on the wrong predictor – current job performance.

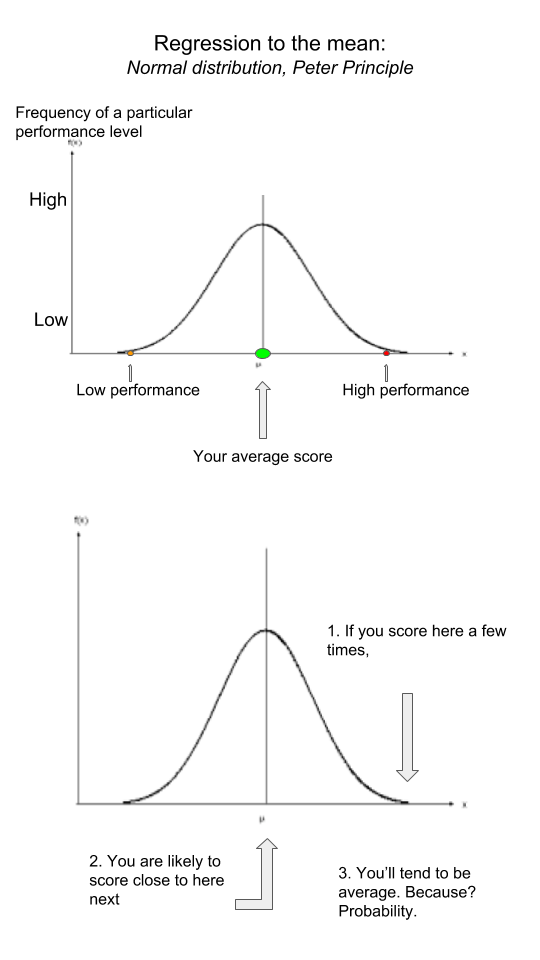

Edward P. Lazear[5] took a different approach to understanding the Peter principle. He says that the incompetence is not a mistake committed by an employer/employee. It is a statistical artifact. Let us see how. He argues that regression to the mean is at play. What does that mean?

Regression to the mean is a statistical phenomenon where one variable tends to be closer to the expected average if it was measured to be extreme. Say you are playing a game on your phone. You make a score of 1000, which is really high. The next time you play, your score is likely to be close to the mean. If you’ve scored very poorly on an exam, you are just statistically likely to score better if you retake it.

Variables that are measured to be extreme (high or low) tend to move toward the average on the next measurement.

Why is this so important for understanding promotions and workplace incompetence?

Say employee X has been outperforming everyone for a good 3 months and his sales were incredible. He might earn a promotion. Every sales rep wants to be that guy right? This guy is likely to suck at sales right after a quick promotion. Why? His performance will regress toward the mean. He will be average in his next sales round. Promotion or no promotion, he would still regress toward the mean.

This is also why movie sequels tend to worse than the first one or music albums have a few hits and a few average ones. It is unlikely that every song written by an artist turns out to be a hit. Not every movie in a movie series turns out to be amazing (Sharknado 1 to 6 is a clear exception). One could expect 1 out of a few thousand artists to produce a significant number of hits. It is statistically expected.

So regression to the mean explains the peter principle in a way that makes the principle an artifact.

Let us look at a related question. Is the training offered after a promotion effective? The training is often designed to reduce the disparity between the current performance level and newer job demands.

- A case study[7] on a big telecommunication company in Uganda shows that training has effectively improved employee performance.

- A review of existing literature on training[8] on employee performance shows that training is effective.

- Even in the Indian Banking Sector[9], training is seen to positively impact work performance.

I could list all the studies I can find, but the general consensus is that training is helpful.

So why the incompetence after promotion? Is it that people only feel that their colleagues & seniors suck at their job?

Behold:

The above- average effect. Or the superiority bias. Or the leniency error. Or the Wobegon effect.

All of these terms point to one thing: People judge themselves to be better than the average across all facets of life & self – memory, skills, social standing, work, entitlement, etc.

This superiority illusion[10] is why the majority of drivers think they are better than average. But you know… Only 50% of all drivers can be better than average. Not 90%, Not 80%, Not 60%. Just 50. That is a statistical fact. It is by definition that exactly half the people will be below average and exactly half the people will be above average.

The IgNobel prize

Alessandro Pluchino, Andrea Rapisarda, and Cesare Garofalo (2010) mathematically showed organizations would perform better if they promoted people randomly in their paper that won the IgNobel prize[11]. This prize is awarded to research that sounds funny but makes you think about the reality in new, valuable ways.

A harsh lesson for CEOs and HR – promote at random. Sounds silly and nonsensical and moral-breaking, but the researchers showed an organization would perform better if random people were promoted. They did this by using game theory and simulations that tested different promotional strategies for global organizational efficiency. They found evidence for the Peter Principle – ‘Every new member in a hierarchical organization climbs the hierarchy until he/she reaches his/her level of maximum incompetence’. According to their simulation, if the Peter Principle has to be avoided – that means every promoted member is not promoted to a position where their core competency changes, the best alternative is to randomly promote anyone or randomly promote the best AND worst performer.

Promotions based on past performance only make sense if the promption means doing a very related job. If the promotion changes core competencies, you activate the peter principle.

Potential solution: Give more raises instead of title promotions so people continue doing the job they excel at instead of starting over at a new skill they have never rehearsed.

Let us review what the research says:

- Companies promote employees based on their current performance even though that does not predict good performance in the next job profile.

- Training modules to improve productivity are mostly useful.

- Regression to the mean shows that one would tend to have average performance if the previous performance was exceptionally high. Consistency in high performance is rare, statistically rare.

- People feel they are better than others when they are usually not. Their self-evaluation is inflated, and that is a feeling, not a fact.

- Promoting at random might just be more valuable to the company.

Everybody doesn’t suck. Nor do you. Not always. Research shows that this is an artifact of the nature of performance over time and the promotional system. We tend to be at our own average.

The 5 arguments I’ve highlighted make a case that the Peter principle is True & False at the same time.

At the feeling level, it might be true. At an objective level, where we say the employees are incompetent, it might not be true. After all, when training is implemented, they improve. If you promote people at random, you risk losing all employees because they feel it is unfair.

Suppose you do face a serious PP issue (Peter Principle, what were you thinking?). What do you do then? Do you try to figure out why everybody sucks at their job or do you try to understand and counter this artifact?

8 ways to overcome the Peter principle and counter the feeling of incompetence

Let us look at how we can overcome the Peter principle now. We will no longer focus on why everyone sucks.

These are my recommendations:

1. Training in the company should focus on global training as well as a here & now training where employees learn to be more competent on the job. Not in a separate ‘lecture series’ once a year that may or may not have lasting effects. This also ensures that there fewer periods or relative incompetency between 2 training sessions.

2. Employees & employers learn to evaluate work objectively and give proper feedback based on performance. This will enable accurate reality checks. No judgment, no opinion, just fact-driven feedback.

3. Decisions to promote can be based on assessing future skill needs rather than make predictions on existing skills.

4. The transition to a promotion can be smoothened by offering training before a promotion, a trial period, and incremental advancement in task demands.

5. If promotions require skill pivots such as technical coding to managing coders and promotions are due, a pay raise with the same profile will help. Then, refer to point 4.

6. Each level of an organizational hierarchy can have multiple sections. Within each section, there are job profiles and responsibilities that are higher than the next up in the hierarchy. This would help with observational learning & familiarity with what the future entails.

7. Competition is good, but cooperation w/ a hint of competition is better. When people work together cooperatively, they tend to identify with a unit of people. This tendency can moderately promote the idea of shared contribution. This will help counter the above-average effect in the workplace.

8. Look at what an employee needs. Some need well being, job satisfaction at the level of involvement (mutual respect & engagement). People want to be valued in the workplace. Promotions don’t always guarantee happiness in the workplace. Employers need to explore what satisfies their employees before using promotions to make them happy. If you are interested in looking at the numbers, here you go[12]. In summary, the correlations between job satisfaction & previous promotions, and small increases in wages are really low. Significant, but low.

I recommend a book called The Science of Story[13]. I’ve drawn these tips after reading that book. It’s a pretty solid book on brand development & the purpose of a workforce. It’s a light read. Quite useful if you are running a start-up.

I’ll conclude by saying that the Peter principle is conditionally true but and subjective in nature. It’s more about human perception than an accurate representation of reality.

You might find this interesting:

Is listening to music at work a good idea?

Sources

[2]: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-FiW8Rg3CAdc/W31Ig45hMHI/AAAAAAAAKEA/DRXUqwWseuEjksNhc0fau9KbmGWVSIFswCK4BGAYYCw/s1600/the%2Bpeter%2Bprinciple.jpg

[3]: https://amzn.to/2N4i75c

[4]: http://www.nber.org/papers/w24343

[5]: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/peter-principle-theory-decline

[6]: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-H25ePrPzvOc/W4Bo_wL0q1I/AAAAAAAAKE4/sSARW_IfXZ0yHkFsAfqPkbUlWJ4ZzbBYACK4BGAYYCw/s1600/Regression%2Bto%2Bthe%2Bmean_%25250BNormal%2Bdistribution%252C%2BPeter%2BPrinciple.png

[7]: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/67401/THESIS.pdf?sequence=1

[8]: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/354c/2c8c60f37f5e25f63f557b3573ec366197ae.pdf

[9]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262843202_Impact_of_Training_on_Employee_Performance_A_Study_of_Retail_Banking_Sector_in_India

[10]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusory_superiority

[11]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037843710900822X

[12]: https://academic.csuohio.edu/kosteas_b/Job%20Satisfaction%20and%20Promotions.pdf

[13]: https://www.amazon.in/gp/product/B07B66W7TD/ref=as_li_qf_asin_il_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=adityashukla1-21&creative=24630&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=B07B66W7TD&linkId=73942ee6df614fdbe7f9886da139768f

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.

[2]

[2] [6]

[6]

Thank you. Age, learning, and adaptability is a whole new issue. Giving training isn't enough, I agree. Unless, training is seamlessly a part of the job and is designed for adaptability, not a module that aims at imparting knowledge/skills. I believe any age group can be trained if certain conditions are met with.

Your comment reminded me of the movie – The intern, super awesome movie about a high achieving start-up girl who grows the company beyond control and then brings in a senior intern program.

Thanks Mukul, you bring up excellent points. The onus of learning should be on the employee even if the system is officially held responsible. Your second point sounds like the flip-side of the peter principle – why should there be incompetence at any level if individuals & companies actively choose to fill the gap between existing skills and needed skills?

Hey, thanks for sharing. I'll probably read the sequel soon. The peter principle certainly helped me equip myself with a new way to look at skills and performance in a job context.

A well reaserched article. In Nationalised Banks , this problem gets amplified due to shortage of multi-talented people at the top. Just giving training does not solve the issue, as the age factor plays important role in adopting new skills.

Well written and pertinent article for the growth of an enterprise. I liked the research, presentation, inferences drawn, and actions proposed. As I read through it, a couple of additional perspectives also came to my mind.

1. Any organization is a collection of individuals, and every individual needs to focus on themselves and their competence in direct proportion to their level in the organization, or inversely to the number of peers they have.

2. The growth of the organization is a result of the growth of the individuals that comprise it at different levels. Rising to 'one's level of incompetence' is actually rising to 'the point at which one stops learning'. The objective of the organization must be to assess, encourage and support the learning motivation of its people.

Thank you for the nice article.

Hey! I just recently had read the 'The Peter Prescription' (the sequel to 'The Peter Principle' ?) and I learnt a lot from it, it's nice to see someone else talk about it too. It's true, it made me rethink a lot of accepted societal norms, about taking up promotions without considering my competency for the next role etc.

Great point about promoting for potential of future performance rather than past good work. Also, training does make a big difference, but most organizations end up reducing the trainings imparted at senior levels, because they think seniors are just expected to learn on the job. Well-run organizations promote only when there are positions open and not to reward past performance. That may work only for the first promotion.

Overall, an excellent set of points. Regression to the mean makes perfect sense. I got a new perspective on this badly abused principle, which is not always in effect but is perceived to be in effect and is just accepted instead of being dealt with, ruining many careers in the process.

In the Peter Prescription, he talks a lot about how to overcome the Peter Principle too!