You may have heard of the zero-sum game: Someone’s loss is your gain. It’s cited as an economic concept. For every + there is a -. Sharing a pizza is a zero-sum game. If you take a slice, that means you are taking away a limited resource, and someone else is not getting it. When resources are limited, we usually see a zero-sum game. There are non-zero-sum games too. A viral infection, for example. One person’s loss is other people’s loss because an infected person can spread. Everyone wins, or everyone loses. With respect to gains and losses, there is symmetry.

In a way, the zero-sum game captures an equilibrium or balance. There is something similar, but deeper than that. I call it the “symmetry impulse.”

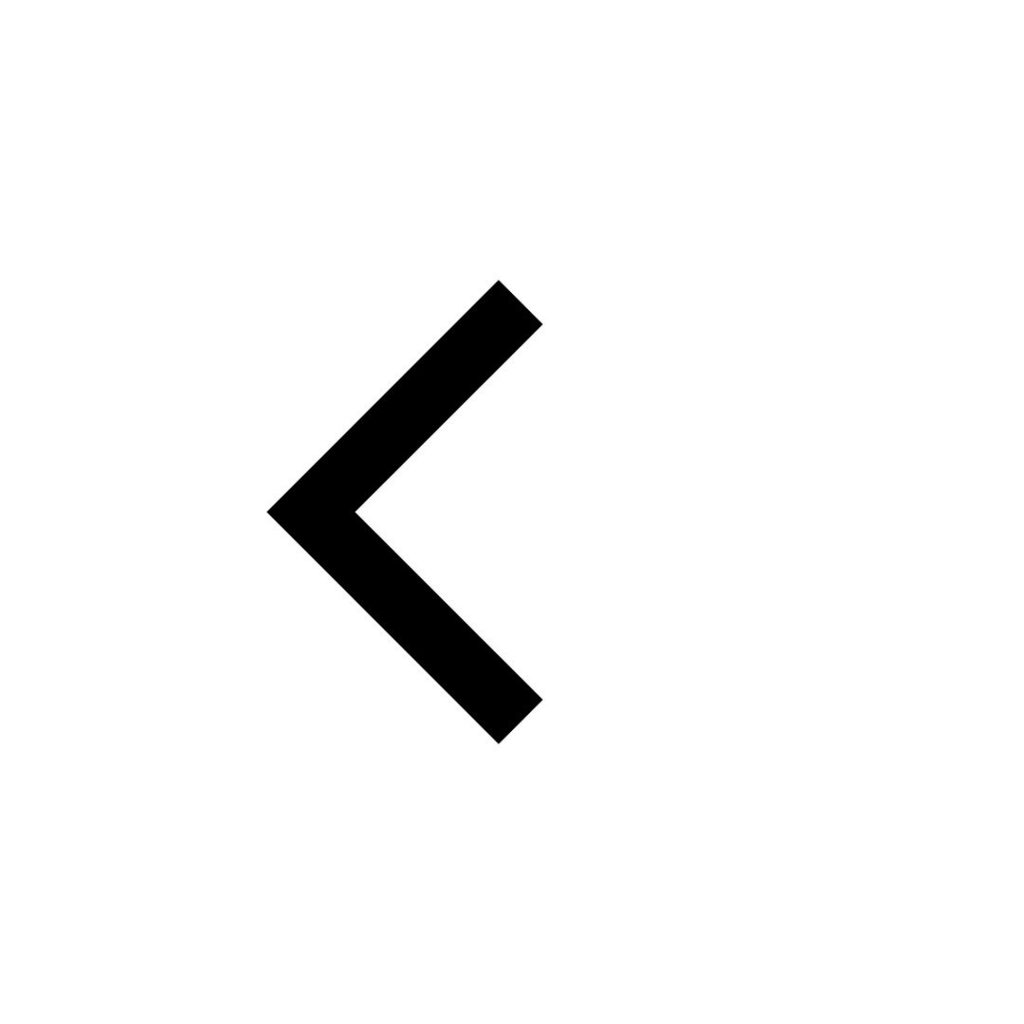

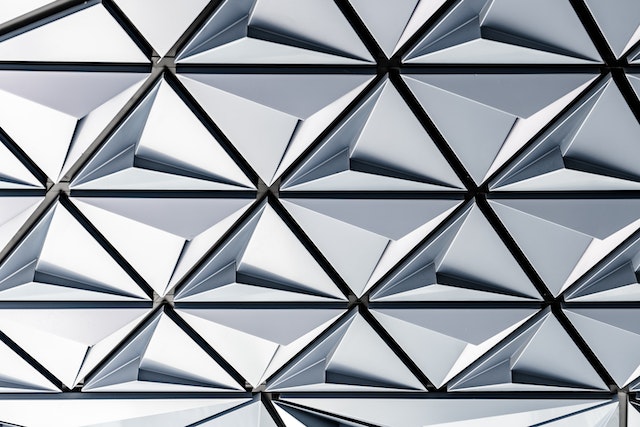

Complete the picture below.

You probably thought this.

The symmetry impulse

The symmetry impulse: People use symmetry to complete a process and make guesses, to complete the “big picture”. This impulse goes beyond visuals and becomes “cognitive” by forming a mechanism to guide thinking, problem-solving, judgments, and reasoning when there is insufficient information. It brings out assumptions and beliefs that feel appropriate but may not be.

- If a product is really good, it must be expensive.

- If a medicine is really effective, it must have brutal side effects.

- If I am going to say sorry, you have to too.

- If there are 10 pros to an idea, there must be an equal proportion of cons

- If a medicine is useless, it probably has no harm

- If a person is really smart, they probably have no social skills

- A loving-caring person is probably dumb

- If a team has 5 males, it should also have 5 females to create balance.

Popular concepts like Yin and Yang, and Karma are based on the same principle. Seeking symmetry is a deep psychological tendency that guides our theories, interpretations, and choices.

We like to complete our judgments, decisions, interpretations, conclusions, and half-baked information using the symmetry heuristic.

– if something is missing, we use symmetry to complete it

– we assume symmetry or a hypothetical balance exists instinctively

Every good has a bad, we assume.

The symmetry impulse is a heuristic – it’s a default tendency, a shortcut for times we don’t have enough details.

Types of symmetry

- Positive-negative symmetry (valence symmetry): Ideas like yin and yang, pros and cons, 2 sides of the same coin, balanced news coverage, etc., is a simple way to conceptualize the world where the positives are balanced with the negatives. Another way is seen in storytelling – “In brightest day, in blackest night, no evil shall escape my sight, let those who worship evil’s might, beware my power, Green Lantern’s Light. In our darkest hour, there will be light.”

- Behavioral symmetry: Human behavior follows physical and metaphorical symmetry between body parts or in interpersonal relationships. Anger is an emotional response to asymmetry in how others treat you and how you treat them. Research suggests anger evolved as a way to restore symmetry. Dance moves, especially simpler dances like Zumba, which have an easier learning curve, rely on symmetry for easy teaching and aesthetic appeal.

- Extrapolation symmetry: When faced with unknown or incomplete information, people try to complete it with some form of symmetry. The incomplete shape in this article is one example.

- Directional symmetry: Some symmetry is across time, where we naturally expect something that rises to fall, at least in the short term. A musical sequence that escalates must come back and resolve itself toward some center (called the root). Market trends like recessions and bubbles are also symmetrical predictions.

- Cause-effect symmetry: People generally believe a large event must have a large cause, and a small event must have a small cause. When either the cause or effect is unknown, people believe the cause and effect must be proportional. This is the proportionality bias.

- Reflectional/bilateral symmetry: Some symmetries are dependent on the left and right sides of a diagram or object being similar. This probably stems from most species and their brains developing symmetrical left and right body parts.

- The equilibrium/balance symmetry: While thinking, we assume a central point in information around which there are opinions or objects. For example, if one says climate change is real and the other says it’s a hoax, the equilibrium symmetry will be an impulse to conclude that the truth is somewhere in between. The hypothesis, antithesis, and synthesis trajectory of thinking is a balance symmetry. When there is one idea, the next idea is its opposite, and then the follow-up is the best of both worlds. We see this in music genres, art, social values, product development, etc.

- Social symmetry: When making decisions about people, we assume symmetry between people. Opposites attract, teams need equal men and women, fair assessments through people with opposing views to avoid bias, etc. Decisions about hiring, dating, social gatherings, etc., often include balancing people out on the assumption that there are opposites.

How deep is the symmetry impulse?

Symmetry lies in biology where microstructures like cells and macrostructures like the brain have at least 1 axis of symmetry (left and right hemispheres of the brain). Newer theories of how the mind works say that mental phenomena follow rules similar to biological mechanisms. So logically[1], when symmetry lies in biology, it should lie in our thought processes in some capacity.

Symmetry in faces has probably evolved as a quick indicator of healthy genes, so people generally find symmetrical faces attractive. However, this preference changes under different circumstances. For example, menstruating women have different preferences throughout their cycle. Generally, women prefer symmetrical faces most, and for short-term partners, when they are most fertile[2].

We prefer[3] symmetry in shapes and faces, but not landscapes. One reason is that faces and other visual templates formed through everyday objects, architecture, geometrical learning, etc., have partially trained the brain to expect symmetry, except for in landscapes, where we have learned to expect asymmetry and randomness. One offshoot of this is that nature-mimicking objects are less convincing when they feel formulaic or too patterned. Musicians also stand by the idea that randomness and some violation of symmetry create a unique form of beauty. That oddity often triggers earworms.

Bumblebees prefer symmetrical flowers to non-symmetrical flowers, probably because symmetrical flowers produce more nectar[4]. Research has documented that almost everyone in the animal kingdom has some form of preference for symmetry in their environment or their potential mates.

Symmetry in art and architecture is also universally loved, but a human’s aesthetic preferences evolve over time. One study[5] on 4-year-old children suggests children pay more attention to symmetrical shapes but don’t necessarily prefer them over asymmetrical shapes, suggesting symmetry/asymmetry preferences start changing early in childhood.

The root of a symmetry bias[6] is unclear, but researchers say it comes from perceptual fluency – easy to detect, and modeling fluency – easy to simulate the symmetrical object in the mind. This is continuously reinforced because it works. However, this pattern isn’t fully universal because females show no clear preference for symmetry in everyday objects, whereas men do.

Taking this preference further for the symmetry impulse, we can simplify ambiguous information or complete incomplete/uncertain information using symmetry. Since we have a preference, it might be possible that symmetry is our default approach to imposing structure in a chaotic, uncertain world. This is again reinforced through learning because symmetry brought about ease of understanding and aesthetic beauty, and more innate behaviors like mate-seeking relied on it. Through continuous use of symmetry in newer domains, it likely generalized as a default.

One principle of photography and design[7] is to balance elements in the visual and create symmetry. Designers often say something is balanced when an infographic or photo is equally balanced with roughly equal detail in the left and right halves.

Taking another point of view, one based on “compression,” makes the symmetry impulse more fascinating. Symmetry may be the brain’s fastest way to compress information. And this compression algorithm is then used to reduce uncertainty in evaluating unknown information. For example, a square is conceptualized as 4 equal sides instead of 4 unique sides of equal lengths. Another way we compress information is through metaphor and analogies, which are themselves based on symmetrically aligning a metaphor with some new information.

Symmetry may also emerge from binary thinking. When we do not have enough information, we often resort to binaries – something is or is not. For example, something red on a tree is either a fruit or not. With more information, the next evaluation would then be – is it a fruit or a flower? Experience and expectations would change the probability of whether the red object is a fruit or a flower. Metaphors like the heart vs. the mind (should you listen to your heart or follow your mind?) are also a binary way of thinking. Because, it is easy to conceptualize even if the details are a lot more complicated. In certain mental health issues like anxiety, there is black-and-white thinking which simplifies judgments into 2 extreme variations – something is either good or bad.

In physics, symmetry is a way to conceptualize particles and systems. There is symmetry when some property of a particle or system doesn’t change when it is rotated or transformed. This is seen at a mathematical level and also at the observable material level. For example, a hexagon can be rotated along its axis of symmetry, and its layout doesn’t change. Similarly, there are asymmetries in particles where rotating a particle changes its inherent properties (this is something I do not understand at all so will leave you with this for further reading[8]).

Geometrical thinking as seen in creating grids and the numbering system where each natural number is equidistant from its preceding and succeeding number may be a direct application of our symmetry impulse into formal science.

Symmetry, in a way, contains repetition. In the diagram at the start of this article, image 1 is a single pattern. Image 2 is a repetition of that pattern. Repetition is a general preference for ease of processing and a simple way to reason or create art. Repetition in advertisements and communication make specific points sticky. Repetition increases perceptual fluency and appeal, and it’s easy to use, so we may default to the idea of repetition for completing work.

Symmetries, repetition, similarity, or duplicates are easier to remember too[9], making it a good option for “completeness” or “wholeness.” When something is memorable and feels complete, we assign more meaning to it.

Gestalt psychology focuses on how humans perceive “whole forms” of assumed patterns using incomplete information. One of the principles is symmetry, where missing information in a visual is added based on symmetry. Another principle is continuation, where a pattern is continued the way it started.

I also argue, in another article, that giving something a pattern is one form of creating meaning, so completing a pattern with symmetry is one way to make incomplete information more meaningful. Essentially, chaotic or isolated information is given structure, and that structure represents the simplest layer of meaning. An age-old example is assigning animal shapes to star constellations. Without those superimposed images, the stars feel random and meaningless.

A simple answer for why we use symmetry is that a pattern becomes better with symmetry. In gestalt psychology[10], a pattern is considered a good pattern if it contains symmetries. In a way, a pattern can be improved with more “goodness” by adding symmetry to it. So essentially, if people are driven to improve something or complete the picture, symmetry is a principle to use.

Thomas Wynn[11] says symmetries are universally understood so we can trace the evolution of human cognition in archeological records using symmetry in artifacts. Symmetry is a recognizable pattern, so it’s easy to communicate and depict, and it requires the least amount of rules to comprehend the concept compared to other complex artifacts. A form of symmetry called reflectional symmetry (along a vertical axis or duplicating as if there is a reflection of the object) is likely to be a pattern that is understood by the brain without paying any attention. That is we perceive the symmetry before consciously evaluating if it exists or not, instant detection.

Humans are driven to reduce uncertainty and seek cognitive closure[12] (give structure and meaning to something), they try to make meaning and choose/create patterns to find that meaning. Cognitive closure is a way to order and structure information and reach conclusions, detect patterns, and make predictions. Symmetry offers all.

The symmetry impulse is an epistemic process – it creates knowledge or completes perception using known information and derives more through symmetry, balance, repetition, or similarity.

Sources

[2]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301051107001391

[3]: https://peerj.com/articles/7078/

[4]: https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.92.6.2288

[5]: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-24558-x

[6]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1068/p7057

[7]: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=KAAVAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=balance+in+design&ots=4qlwuZWE_u&sig=K_MLQhbFNj0fLTukHwkuSikPcxM&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=balance%20in%20design&f=false

[8]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0039368114000879

[9]: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1418892

[10]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-98787-001

[11]: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas-Wynn-3/publication/10645217_Archaeology_and_Cognitive_Evolution/links/60d36828458515ae7da7457d/Archaeology-and-Cognitive-Evolution.pdf

[12]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-07984-001

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.