At the simplest level, memory can be viewed as a 3-step process – encoding, storage, and retrieval. But you’ll see the story gets a lot more complex, and a secret hidden player is doing all the heavy lifting from the shadows. And you can leverage that player’s input, literally, to develop expert-level memory.

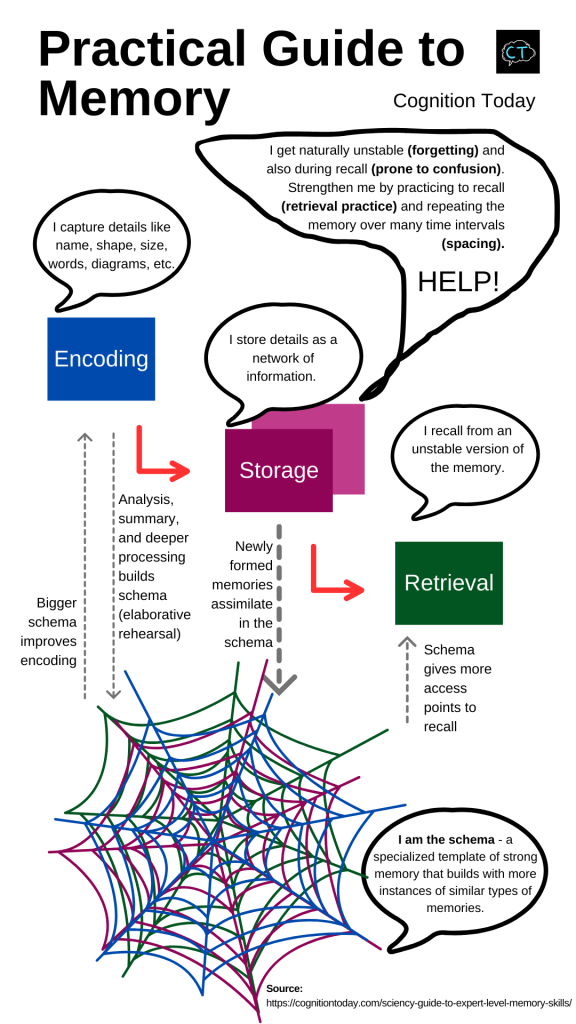

When we learn something, information is encoded. Names, faces, shapes, concepts, sensory details, words, arrangements, etc., are captured by the brain. This information is supposed to go into our memory storage. The encoded parts are converted into relatively stable neural representations. When we recall, that information is retrieved. Those neural representations are accessed and produced as a behavior like stating a fact, recognizing something, getting an idea, etc.

This was the discovery of many psychologists who conducted experiments and created mathematical representations of human memory[1]. Those laid the foundation and others uncovered many more nuances. I’ve consolidated some of those theories and nuances into one practical framework, which can be applied to hobby learning like acquiring musical or chess skills, learning in the classroom, or upskilling for work.

Let’s look at some nuances.

For information to be encoded really well and actually stay in the storage so that it can be recalled[2], we need “elaborative rehearsal“. This happens by paying attention, analyzing, connecting it to past knowledge, etc. In contrast, we use “maintenance rehearsal” to remember something for a very short duration, like a security pin code, or a temporary delivery token number, etc.

In everyday life, elaboration rehearsal is essentially some form of active effortful thinking about newly learned information. For e.g., when you learn about different trees, analyzing different parts of the tree and different leaf patterns, understanding the scientific naming system, and learning about their habitats, etc., are ways to elaborate on that information. Doing this strengthens memory.

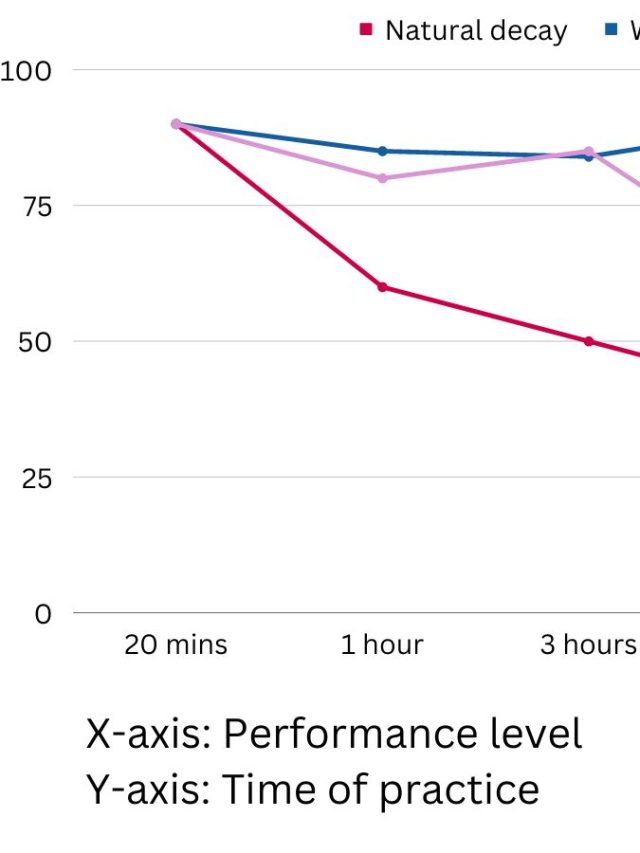

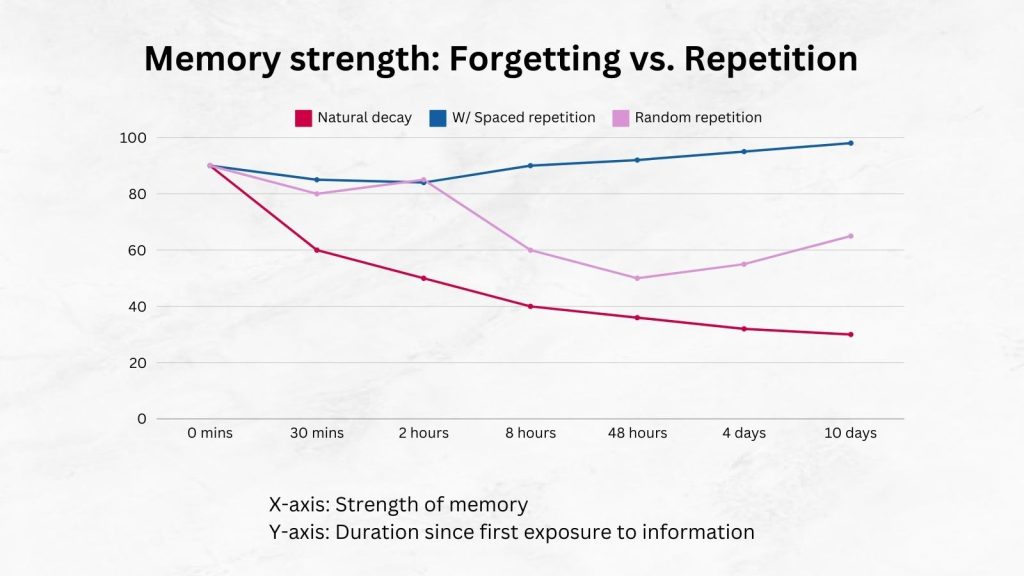

No matter what, the stored memory is likely to decay and disappear, which we call forgetting[3]. Forgetting happens in the brain as neurons lose their connectivity over time. Once the connection goes, the memory is gone. This happens in almost every case of remembering something. It follows a curve (the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve). And, memory/learning has to be reinforced (repeated, reviewed, applied in the world, etc.) to counter the forgetting.

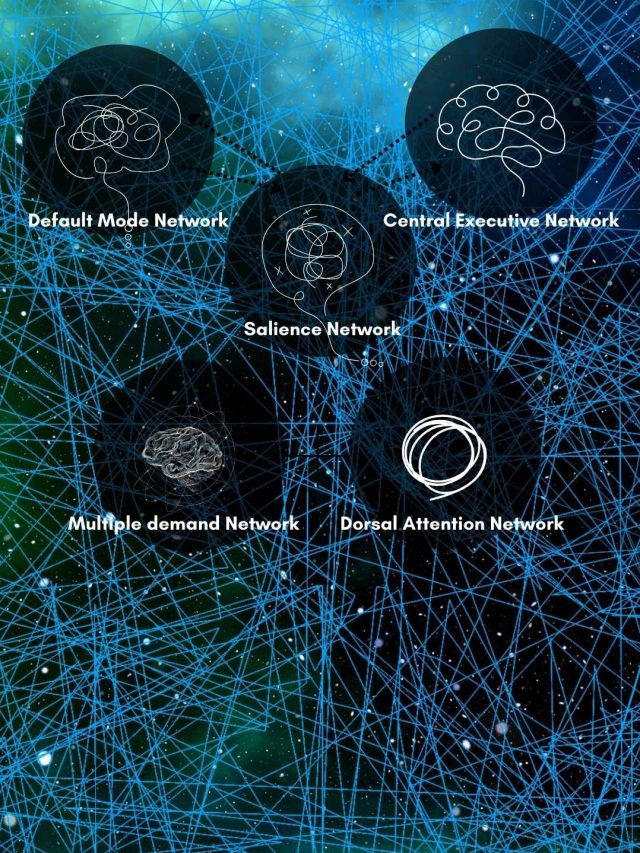

Memorizing and Remembering are 2 different processes governed by different neural circuits[4] and both have different challenges when it comes to overall memory.

For information to be retrieved (remembered), a separate pathway begins that weakens the memory and pulls a soft copy out (not the original). The originally formed memory is destabilized during this process[5]. The copying process makes the memory “labile” – prone to changes[6] – aka confusion, mistakes, mixing-up, embellishing, and biases. These changes can happen due to any number of unexpected factors like taking medication, having too many similar experiences, dealing with confusing words & ideas, hearing something in the background, remembering what someone else said, etc. Essentially, memory gets reconstructed[7] when trying to recall, and that recreation can get contaminated with confusing details like mixing up locations, confusing words, falsely remembering something else because it makes sense, etc. To reduce the chances of this, the initial strength of memory matters which increases with elaboration rehearsal. But there are other ways to strengthen it, too.

- Spacing – when a new learning is periodically reinforced or recall, it strengthens. An application of this for studying academic content is to learn in a distributed way over time instead of brute-force repetition in one go and not reviewing again.

- Retrieval practice – since recalling is a separate neural pathway, remembering becomes a different skill than committing something to memory by repetition.

Both these techniques are popularly used by those who study for exams.

Memory in the real world is about retrieval. The information has to be pulled accurately. This separate pathway has to be rehearsed. So recalling information is a practice-based skill. The more you try to recall, the more you are able to recall. In an examination environment, this skill matters a lot more because a test is a test of recall, not a journey of learning.

But this isn’t enough.

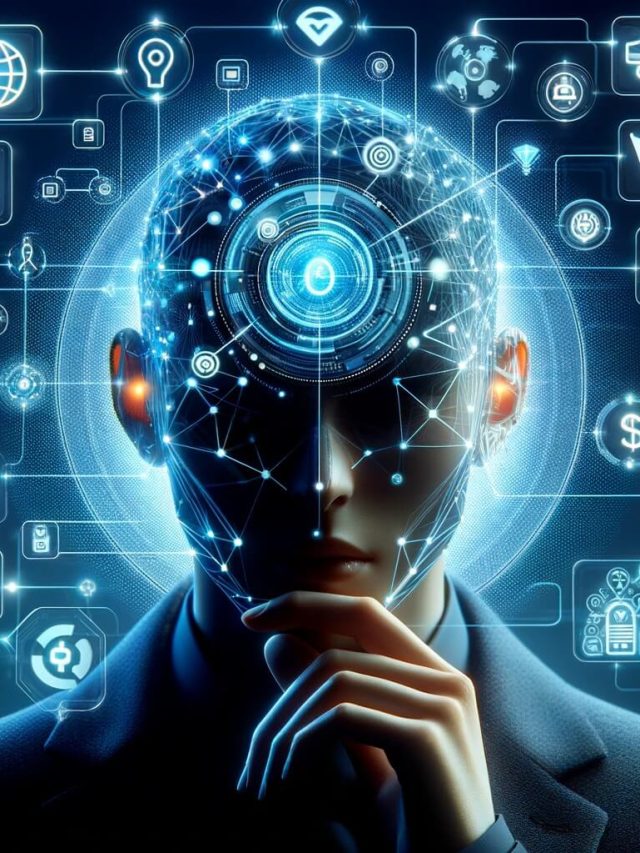

Memory Schemas – The MVP

For memory to be encoded properly AND also be accessible for retrieval without being too labile (unstable), we need to develop “memory schemas”[8]. These memory schemas are templates of information that “hold” the information. They are an associative network with multiple nodes. Schemas strengthen encoding and also retrieval because schemas are an interlinked web of related information that reinforces new information, and they also have hooks to pull while recalling some target information.

When a musician learns for years, remembering a large amount of songs isn’t difficult. But a beginner might struggle. The same goes for chess players. A beginner would struggle with remembering a few patterns on the board, but a pro will remember hundreds of patterns. The same goes with cooking.

The defining feature of these schemas is that they are meaningful patterns of information, not random patterns. Although, experts do remember even random information a little better than novices. Researchers explain this happens because even many random patterns can be broken down into smaller meaningful groupings. E.g., studies have shown that experts[9] recall random chess positions better than novices.

Apart from physical skills like music and dance, schemas work for cognitive aspects too – like remembering names and faces really well, remembering dates in a historical context, remembering the names of insects and their habitat, etc.

One of the core features of these schemas is that they contain large patterns of how things work and how things go together. E.g., for a musician, a basic sequence of notes can be a pattern which tries to compress and capture new songs. The same goes for remembering dates in a historical context. A person could remember dates really well because there is a whole pattern of events that loosely make a story of what follows what. There is some internal logic to these patterns.

Essentially, a schema is a set of patterns with many unique connections and some odd un-patterned information that stands out. You’ll see through memorizing experiences – as I’ve said in this article – pattern recognition sits on the cognitive throne.

A common way to build this pattern is to use what psychologists call “chunking“. It is a way to group information together such that each group makes sense. E.g., a grocery list of 20 items can be chunked into 5 categories like food, drinks, cleaning items, and medicines.

But, these chunks aren’t enough to build schemas. Deep thinking (elaboration rehearsal), chunking, finding patterns, repetition, variations of a skill, multiple contexts, etc., make the schema dense.

Now this has 2 benefits for memory. A dense schema means there are more stable anchor points for the brain to recall specific target information. E.g., if you have to recall a bird’s name, the habitat can be a hook to recall it. These schemas also form a person’s core “knowledge-base”. More knowledge makes it easier to pay attention to things that are familiar. More knowledge means more familiarity. So, having strong schemas make identifying patterns and new details easier. Which, in turn, means encoding gets easier with better schemas.

This is how the whole memory system comes full circle.

For you to be good at memory in any domain, focus on schemas.

For a more lifestyle approach to improving overall memory, check this out.

For memory techniques to use while learning facts, check this out.

For mnemonic techniques (very specialized tricks), check this out (tutorial)

Sources

[2]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03200764

[3]: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0120644

[4]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn.2017.117

[5]: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/behavioral-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00177/full

[6]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19468955/

[7]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27088497/

[8]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0028393213003990

[9]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13421-016-0663-2?fromPaywallRec=false

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.