Memory and observation can feel like a superpower. Someone like Sheldon Cooper from the big bang theory or a genius like Zack Addy from Bones certainly seem like superheroes in the cognitive domain. Their skills are not unreal.

In reality, we have geniuses like the 5-time chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen, who can remember just about any chess game he has played or watched. Then there are other geniuses called savants, like Kim Peek (now deceased), who had memorized 12,000 books by age 30 and could simultaneously read 2 pages at a time – left eye left page, right eye right page. A modern-day savant Stephen Wiltshire, an artist from the UK, can take 1 look at a city skyline and draw it with incredible detail just from memory. These are extreme cases of people with superior observation and memory.

You may feel you are bad at observing, bad at remembering things, and think nothing can be done about it. Don’t worry; there are ways to dramatically improve your observation skills.

Observation is simply capturing the most amount of details with your attention and transferring them to long-term memory so you can think and act using those details.

People with exceptional memory

There is little to no documentation of perfect memory people whose observation is so good that they become the best in every area. Kim Peek was an autistic mega-savant, a true expectation. Magnus Carlsen developed a specialized memory for chess configurations through extensive practice. Stephan Wiltshire is an autistic savant too. If you exclude these exceptions, there are 3 types of people who have extensive memory for things with just a little observation.

- Hyperthymesiacs: Hyperthymesia[3] is also known as Highly superior autobiographical memory. Autobiographical memory is the memory of personal events. Those with hyperthymesia (only a few dozen recorded) have an exceptional memory for personal experiences. They can remember virtually every past event in their life, including their clothes, date, and surroundings. One theory states that their brains subconsciously revise and remember all of their personal events obsessively, so they tend to remember most details through that rehearsal. Unlike mnemonists, they do not deliberately practice remembering details.

- Memory artists who use mnemonics: Memory world record holders and memory athletes use specialized tricks called mnemonics to remember vast amounts of information. Some people can remember every person’s name in a room of 100 upon hearing it once. Some can list every country and its capital. A notable example is Akira Haraguchi[4], who holds the world record for reciting 100,000 digits of pie from memory over 16 hours. He devised his own system where each number is a kana symbol, so a large sequence of numbers forms a story, which is inherently more memorable than random numbers.

- Those with specialized schema memory: Most people who practice a certain skill develop great memory for patterns within their skill. They develop schemas are memory templates fine-tuned to a specific category of information. Some musicians can remember a vast arrangement of notes by listening to them once. An expert interior designer would remember the precise decor with just one observation. Through learning, we develop a learning schema that becomes a specialized net to capture particular types of information. A chess player would develop a chess schema for positions on a board. A musician would develop a musical schema for chord structures. A coder would develop a logical/algorithmic schema for processes. These schemas make observing information more contextual and therefore improve memory for the things observed.

Most of us aren’t hyperthymesiac, or experts in all areas, or mnemonists. So is our power of observation weak and limited? To a large extent, yes. But there are 4 simple actions you can take to dramatically improve your observation power.

Becoming a careful observer (the basics)

When we think of observation, most might consider seeing and hearing. However, all sensory information can be observed. And it is guided by our attention which selects certain information to process. We can observe the taste, textures in the mouth, smell, bodily feelings, locations, etc.

Mnemonics aren’t the best way to observe and memorize in everyday life because they are specialized skills that take effort and training. Instead, the way to improve observation on average in all contexts is to use existing cognitive processes to strengthen and fortify observed information.

1. Pay attention

Attention is our ability to select information to focus on. Without that selection, memory is rarely formed. It acts as a filter. Good observation means reducing how much information is filtered out. Taking notice is purposeful attention that you sustain. This lets everything you interact with embed in your brain deeper. More processing leads to better memory. So between just looking at something vs. looking at it deeply, the latter creates stronger memory. To make your observation more “sticky,” pay attention to the context too. Contextual information is easier to process than isolated objects.

Research now shows[5] that the time spent observing something and taking notice of a detail (that is storing your immediate environment in your working memory) determines how strong its long-term memory is. So the more you focus and take notice over a period of time while observing, the better your long-term memory will be.

To start paying attention – focus on locations, familiar objects, and faces. We have superior memory systems for all 3, and that can bind your observation into one meaningful scene. If you notice how all elements interact with each other, you can build a story. The brain loves stories, so observing with the mindset of observing a story instead of just plain objects will greatly improve how much you notice.

We tend to first notice things that are excepted. And this creates a problem called “inattentional blindness”. We sometimes do not notice large unexpected changes in the environment. For example, you may not notice that a certain store near your house shut down and there is now an unexpected park, even though you travel that road daily. So to enhance your observation skill, carefully look for changes.

If you have a particular goal for observation like observing only people or various colors or different cars, you can systematically hunt for those specific things in the context they appear. As long as you observe the story there, it’ll be easy.

Our memory during observation is also “filled in” with things that we expect. For example, in a study[6] that showed letters forming a shape, participants hardly noticed that some letters were inverted, and they wrongly observed they were correctly oriented because that was the expectation. Our memories are fragile the moment we form them and expectations can quickly corrupt them and morph them, making us feel we observed something that wasn’t there. This is why people often misremember details about events, parties, and general elements in the background.

The infamous “eye-witness testimony[7]” experiments by Elizabeth Loftus demonstrate this – people sometimes make large-scale errors like misremembering a criminal’s gender or even how many people were there at a crime scene, but confidently use their biases and expectations to “complete” the story. Then, they recall the event, modified through expectations, and say they clearly observed what they think they saw.

2. Verbalize and name it

Putting things into words is very important for 2 reasons. Giving something a name solidifies its memory and understanding. And, the words used to describe something strengthen long-term memory in a way its easier to recall. In fact, words are almost always needed[8] for something to become long-term episodic memory – that’s our memory for events and experiences. This is a process called semanticization where words reinforce long-term memory and become the buttons that retrieve them.

The biggest, most general cognitive tool we have is language. If we do not have the linguistic tools (words/visuals) to represent an idea, we don’t remember or notice it as well. It’s more prone to instant forgetting, and it is treated as sensory noise. If there is no word or visual, the brain thinks of it as a meaningless bit of information and discards it. This state is known as a “hypocognitive[9]” state, and it dramatically worsens observation.

The takeaway here is: assign a word, symbol, or description to everything you notice – words make observation meaningful and facilitate long-term memory.

Telling others reproduces that information. Memorizing and remembering are 2 different processes. After a memory is formed, it is only as good as your access to it. That means “retrieval” takes more importance in everyday life. Retrieval needs practice and proof – you have to test yourself on remembering things, and then your general access to memory improves. Telling others is one way to prove you have successfully observed something.

This does one more thing – called the production effect. When we reproduce information by telling others, we remember it better because it is now reinforced again in the brain. In the learning domain, this is often seen as the “testing effect” or “retrieval practice”. The testing effect says we remember the information we are tested on better than information we are not tested on. Retrieval practice says we need to actively recall something to improve memory because memory and remembering are 2 different processes that can be trained.

4. Improve the observation meta-skill (advanced ideas)

Since what we observe is based on what is familiar and expected, observation improves when the underlying processes that guide memory and attention improve. That is the meta-skill – it is the deeper skill that improves the practical skill.

Building memory schemas: Developing memory templates

While scanning your surroundings, it’ll help to go through a quick category of things and see “stories” or “meaningful patterns”. Categories you can look for are people, objects, brands, vehicles, spoken words, appearances, etc. Stories you can look for are people interacting with each other, a flow of traffic, a movement, a global image of your surrounding, etc.

As you develop these stories and spot categories, your brain will be “initiated” to notice those again, making it easier to do the same in the future. In short, practice observing till you start observing better. In this process, you’ll develop strong memory schemas[10] that make future observations in that category easier[11].

Memory schemas are very powerful knowledge structures in the brain that affect what we notice and remember. They are developed through experience, total knowledge, and practice. The more you practice something in one area, the better your memory schema will be for that area. The more you’ve learned about a situation, the better your schema gets. If you widen your range of all things you are familiar with, you will develop a rich set of memory schemas.

For example, if you have been cooking for a long time, you’ll find it easier to remember the variety of products displayed at a supermarket or vegetable vendor. If you don’t cook, you won’t have a powerful food-related memory schema for ingredients, so it’ll be harder to notice and remember the variety.

A memory schema works as a combination of long-term memory and short-term memory. While observing a landscape, the landscape schema developed through past experience will act as a fishing net to capture new information you are holding in your short-term memory by looking around.

When you develop a wide variety of schemas through experience, you learn to expect more details. So naturally, you tend to observe more because we see what we expect and are prepared to notice. For example, knowing there are 10 varieties of birds around you can create an expectation of 10 different types of nests in the surrounding. Without knowing what birds you have in your area, you wouldn’t expect those nests.

Creating chunks and stories: Grouping observations in a meaningful way

Chunking is grouping information with a common theme. This makes it easier to remember more details because those themes can anchor information to that theme. For example, look at this list of words:

- Table

- Apple

- Keys

- Soda

- Bread

- Cheetah

- Cat

- Chair

- Laptop

- Bottle

This list might be hard to remember, but you can chunk this information into groups and remember it easily. One way to chunk this is:

- Study room (Chair, Table, Keys, Laptop, Bottle)

- Animals (Cheetah, Cat)

- Kitchen (Apple, Soda, Bread)

These groups – study room, animals, kitchen – are chunks with more details. Chunks make information more coherent and give it a real context, and context improves observation. It also improves our ability to visualize.

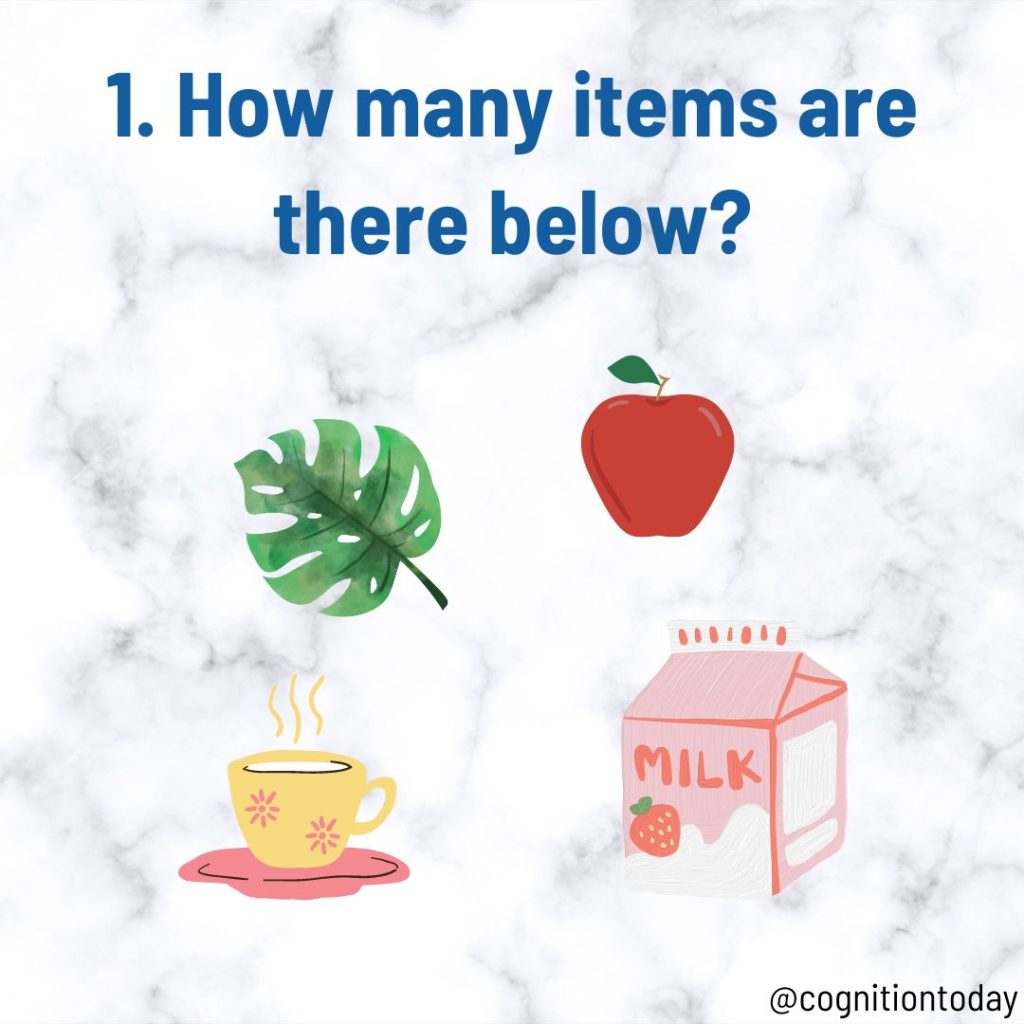

Our visual working memory is limited. Most of the things we observe are items stored in the visual working memory, and then they transfer to long-term memory. Researchers have observed[12] that our visual working memory can hold up to 4 or 5 items. For more complex visual features, we remember fewer details.

On the positive side of this limit, we have familiar situations which generally lower the complexity of that situation. For example, going to an airport for the first time might make you think the airport is a complex scene. But going frequently will give a general idea of how they are. Familiarity makes processing the familiar object easier – the more you’ve sensed it, the easier it is to remember. So it’s easier to remember more details from patterns you already know instead of patterns you do not know.

The basic limit for how much we can remember at a time is 4 units[13]. Without much effort, you would be able to remember 4 random objects. But these 4 units can be “chunks” that contain a lot more coherent information within a chunk. And as you start chunking, you’ll get used to remembering more detailed chunks. Instead of 4 random objects, we can remember 8 different cars if we group them into 4 categories or “chunks”. Chunks have to be meaningful. And the more familiar you are with expected patterns, the more meaningful they seem.

4 is a special number. Humans can instantly recognize there are 4 objects in a visual scene. 1 to 4 items don’t need counting. Beyond 4, they have to count. Unless the pattern they see is already meaningful and familiar. The process of noticing 4 items without counting is called “subitizing”. But knowing patterns can improve this range. For example, if you work extensively with geometrical shapes, you might instantly recognize 5 points arranged as a pentagon without counting. Here, all 5 points are “chunked” into a meaningful group. But 5 random points in no clear shape aren’t chunked, so they require counting. This again shows us that knowing enough meaningful patterns improve our ability to observe.

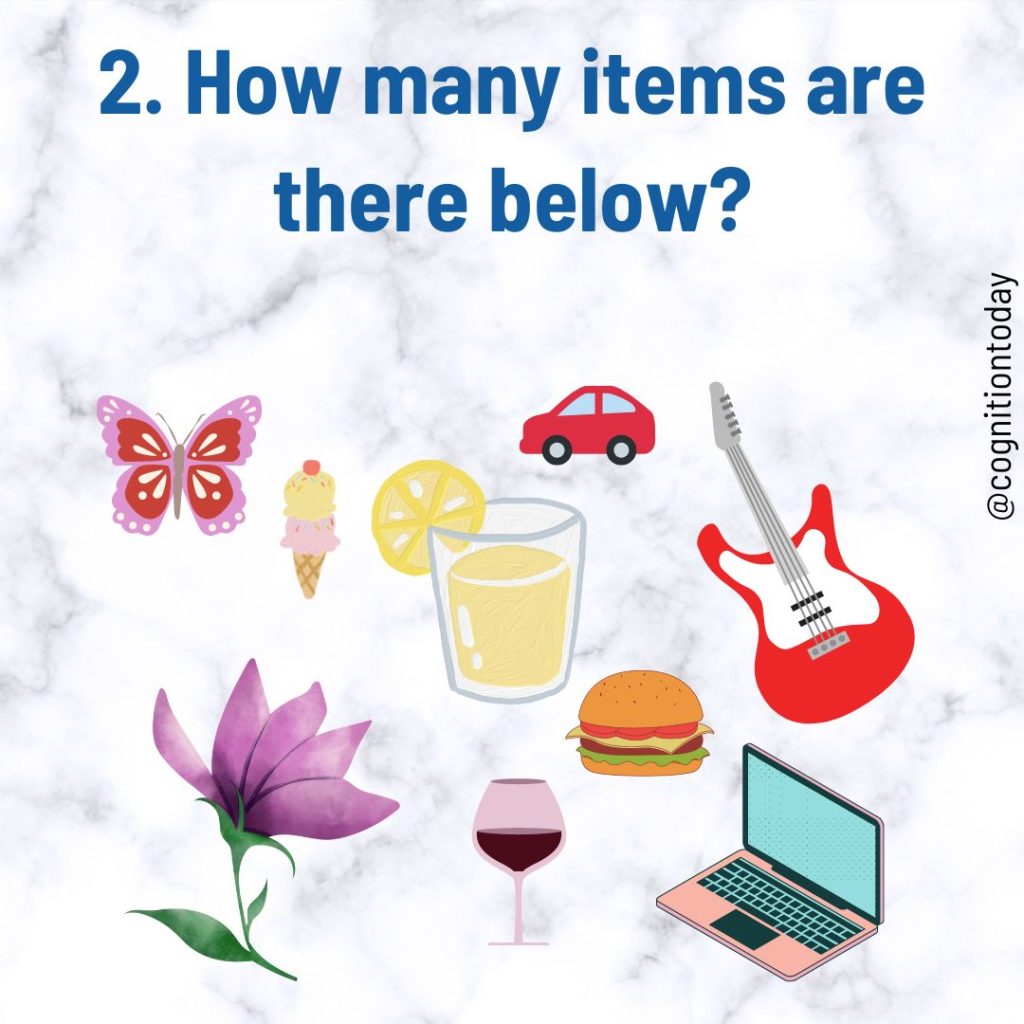

The way you notice information and group stimuli in the surrounding will affect how much you remember. In the above scene, you can build a story – Aditya just finished work on a laptop and nearly spilled lemonade on the keyboard. He then went to the garden to smell a purple flower to refresh his mind. He saw a butterfly near the flower. He then came back, poured a glass of wine, and ordered a burger. Later that night, he drove his red car to buy ice cream.

When you storify the things you observe, they make more sense and are easier to remember.

Story = Pattern = Meaning.

When it comes to observation, you can equate the 3. When you have them, it’s easier to remember them without effort.

Effectively, the 4-unit limit expands to dozens, if not hundreds or thousands. The stronger your chunking ability and memory schema, the more the limit expands.

Ask any passionate hobbyist – a musician would remember dozens of artists they recognize from a concert roster. A passionate biker would remember many new bikes and their nuanced models. A tech enthusiast would remember all the new, popular gadgets on the release radar. The 2 main reasons they have better memory through effortless observation are: they are familiar with the expected items, and they have strong memory schemas.

In short, to observe better, the brain needs to have a meaningful memory schema. Coming back to the example of the chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen, you’ll see profound memory for chess openings comes from a huge memory schema.

Chess is an excellent way to study observation and memory because it resembles reality within limits – there is a location, there are meaningful arrangements of different pieces, there are relationships between them, there are rules, and there are expectations. Looking at how masters observe and remember chess games gives us a deeper insight into how we can observe better in real life.

Research on chess experts and novices[14] shows chess experts have superior memory for meaningful chess arrangements, but their memory accuracy is not as good when the chess positions are random. However, for both meaningful and random arrangements, their memory is better than novices. The key insight here is that chunking and memory schemas work better when the patterns you observe are meaningful and familiar.

Without using specific tricks like mnemonics and intense practice, how much can we actually observe? The answer lies in how many chunks we can remember.

One study[15] shows that each chunk spans, on average, 2 seconds. So 2 seconds of observing a meaningful pattern are enough to embed it in memory if you are familiar with the observed pattern.

To put how much people can learn and then clearly recognize their learning (i.e., observe their learning), let’s look at how many English words an average person speaks and how many chess positions (chunks) a master knows. One study[16] suggests an average 20-year-old American native English speaker knows 42,000 words and learns an additional 6000 by age 60. A chess master[17] knows 50,000 unique, meaningful chess configurations but most likely has fewer chunks (about 10,000) that govern those 50,000 configurations. These chunks are closer to memory schemas because they are templates of positions.

The 4-step process summarized

- Pay attention and take notice of contexts, stories, people, locations, unexpected things, patterns, and objects

- Verbalize and put your observation into words

- Share and tell others what you observe

- Develop the observation meta-skill

- Practice observing till you expand your memory schemas

- Group information meaningfully (chunking) – meaning comes from recognizable patterns and expectations

- Get familiar with more unknown things, so more information is inherently meaningful

Sources

[2]: https://www.instagram.com/p/CLsH5MQDKpX/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading

[3]: http://dr.limu.edu.ly/handle/123456789/754

[4]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akira_Haraguchi

[5]: https://www.journalofcognition.org/articles/10.5334/joc.245/

[6]: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0283257

[7]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/acp.3542

[8]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12146685/

[9]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1037/gpr0000126

[10]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0028393213003990

[11]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1364661317300864

[12]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502006.x?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.1

[13]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0963721409359277

[14]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022096583710386

[15]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/741942359

[16]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116/full

[17]: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.3758/BF03200937.pdf

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.