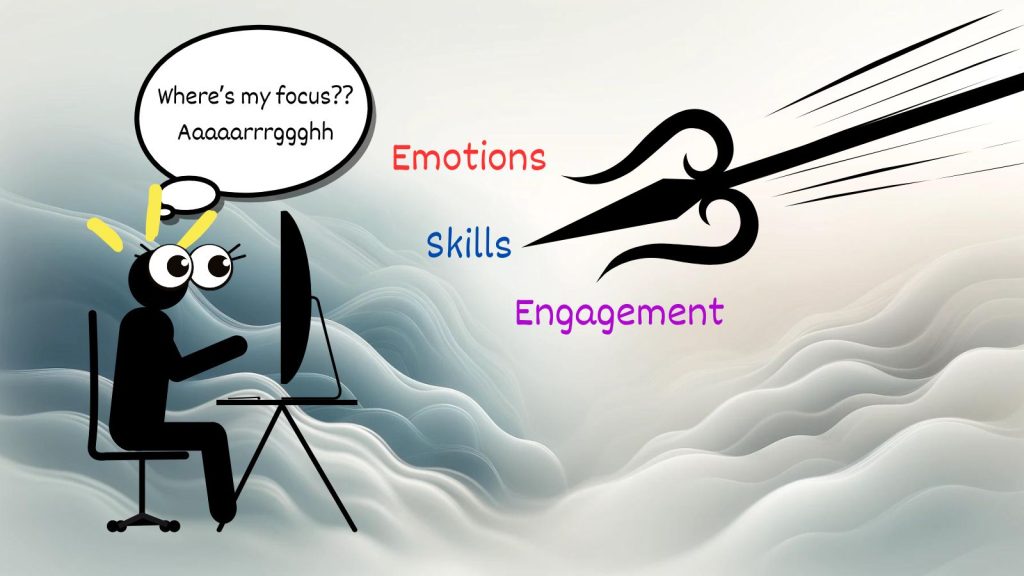

A temporary loss of focus is expected when you work a lot. And you don’t have to blame your attention span. Blame emotions, engagement, and skill.

If you don’t read through this article, it means the article isn’t motivating, engaging, and rewarding you, it doesn’t mean your attention span is low.

The basics first, resting and sleeping maintains the brain’s ability to focus by doing biological repairs and upkeep. Sleep deprivation increases lapses in attention[1] (absent minded-ness, zoning-out, etc.). Caffeine can make you alert by blocking adenosine (the lethargy inducing chemical in the brain). Exercise can make you feel energetic[2] by heightening bodily arousal, cognitive ability, and endorphins (positive-emotion-inducing hormone). But beyond these effects, the bigger problem is about handling emotions, how a task engages you, and how your skills are used.

What does attention even mean?

For the sake of this article, I’ll define focus (in the casual sense) as our ability to pay attention, sustain it, and meet goals. We’ll get to attention in a bit.

Imagine this: You can scroll Instagram for 2 hours straight and lose time, you can read a book for 3 hours, but you can’t do a task at work without getting distracted every 5 minutes. What’s the deal here?

Psychologists and laypeople have often loosely used the word attention to mean many different things – focus, vigilance, memory, observation, concentration, commitment to goals, etc., which people have interpreted as an innate, default skill.

But, the reality is that attention is task-dependent, not a default resource you have.

Your attention and the ability to multi-task will depend on the demand put on your brain by each task, the emotions involved in the tasks, and your personal capacity to skillfully do the tasks.

Our best theories says that 2 different neural systems guide attention[3]. One system selects and prioritizes information to bring into awareness. This system catches everything from alarm sounds, your name in a crowd, a buzzword. This form of attention is fully dependent on the stimuli. The other system uses motivation, goals, commitment, etc., combined with how engaging/interesting and rewarding a task is to find relevant things to focus on. It also often interrupts the previous system that was supposed to capture a distraction. For example, you may be working on an excel sheet and your phone’s notification sound pulls your attention away. The first system will be responsible for you to look at your phone. The second system will be responsible to get back on task. Both systems combine to begin a state of concentration.

There has been a popular myth – attention spans are down to 8 seconds. This was a statement mindlessly repeated by large news outlets, CEOs of big companies, and marketing gurus on social media. It became gospel and no one questioned it (I have argued with people for 5 years that the stat makes no sense). It was repeated so much that it became a publicly known fact confirmed by confirmation bias.

Long story short, a Microsoft employee discovered the statistic on an unreliable SEO website called Statistics Brain. Their logic for 8 seconds was that people left websites they didn’t like that fast in 2008 (their sample was 25 people). It’s one of those moments where a myth got viral and felt true because it was repeated often (the illusory truth effect)

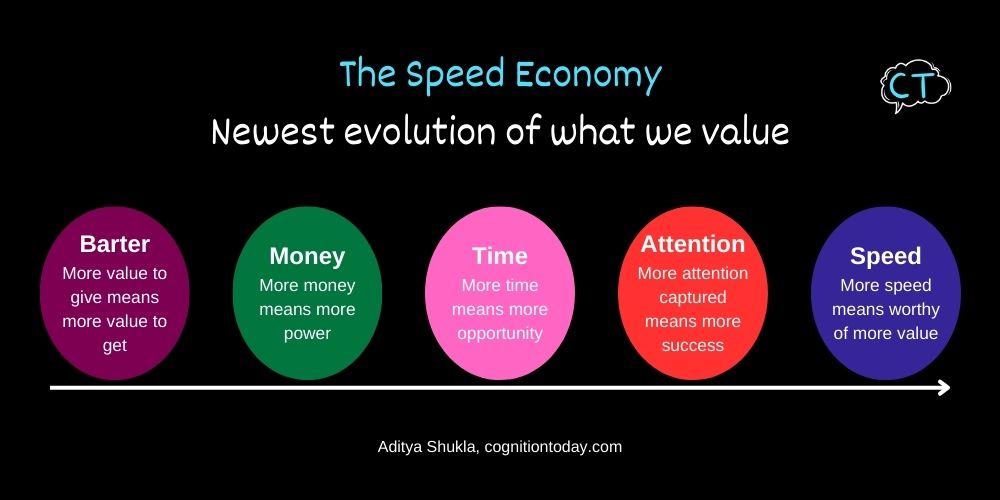

We got used to speed

What changed was the speed at which things change – the speed of social media, the speed of getting medicines, the speed of getting deliveries, the speed of conversations, the speed of television media. All these increases in speed made us expect and want speed. So the technology that was developed alongside also supported speed through faster data, faster downloads, faster processing, shorter videos, dedicating just a few seconds to acquire information, etc. It became a positive feedback loop where everything gets faster and we expect it to keep getting faster, so someone builds technology that makes things even faster. Everything from content to home-delivery focused on speed. Everyone fed the consumers’ expectation of speed. Naturally, the consumer habits settled down on expecting and getting comfortable with speed.

I call this the speed economy. Value is proportional to speed.

This barrage of speed created a problem – what happens when you are used to speed and you have to get comfortable with something slow? People get uncomfortable with the lack of speed. The lack of speed triggers an the avoidance system in us through which we reject, ignore, or avoid things that feel slow.

Attentional budget?

I lured you with a buzzword. We don’t have an attention budget like it’s a limited resource. We have an attention prioritization system. Research shows[4] that some things are worthy of more attention and how we deploy attention can take 1 of 2 pathways, often a mix of both in the real-world.

- Bottom-up attention: You park in a parking lot with only white cars and you realize there is just 1 red car, the rest are white. The car (the stimuli) contrasts with its background. This stimuli is a saliant stimuli commonly called “a singleton”. The attention you pay to it is driven by the standing-out feature of the car. This is called “exogenous” attention. Attention often goes toward distractions because of the salient features of the stimuli.

- Top-down attention: You park in a parking lot with many different cars. Someone asks you to find a Hyundai. The attention you pay to it is now goal-directed and you will start filtering out the cars you see. How long you can focus on the cars to complete the task now depends on your knowledge about cars, knowledge about logos, ability to remember which cars you’ve rejected, which areas of the parking lot you’ve covered, etc. This type of attention is called “endogenous” attention. Focus during work is of this type.

Both of these forces of attention work together when we are trying to concentrate.

From experiments we know our innate ability is “stimulus” prioritization and not attention per se. A task is a stimulus. So is an app, or a sound. Anything that meets all our senses is a stimulus. But a stimulus goes beyond our senses. Our mindwandering thoughts are also a stimulus.

This stimulus is placed in a container called working memory where we use that stimulus and respond to it. Our real understanding of focus begins here. Focus is the commitment to respond to that stimulus adequately and appropriately. For example, if the stimulus you have to act on is an email, your working memory should be dealing with that instead of prioritizing another stimulus like an Instagram notification. The task you are doing is now about that working memory being influenced by: Stimuli prioritization, emotions, sense of reward, and mental effort.

The idea of attention span is a mix of stimuli prioritization and working memory, in the context of cognitive testing. They typically measure the length of time a person can focus on a stimuli and recall it correctly. For example, the digit span test is used to see if a person can remember a sequence of numbers back to back. This tests if the person is paying attention to the numbers and immediately storing them in memory. Other tests of attention include decision-making in which letters are presented one by one on a screen and the test-taker is supposed to press a button only on specific letters. The decision-making can get more complex in other tests.

Tests of attention have not really shown any change in people over time. But, enough real-world examples have wrongly assumed that focus is attention[5]. For example, TED talks were designed to be 18 minutes because they thought 18 minutes is how long people can focus at a stretch. Earlier research said people can take good notes for 10-15 minutes and then they stop. Schools conclude lectures of 40 minutes are long enough for most people to focus. Combining this ambiguous data with the 8 seconds news, we get an unrealistic attention span of 8 seconds to 50 minutes…. which makes no sense because none of the data points measured attention.

Our attention system can also get corrupted because we live in an environment. Our attention can latch on to something that should not pop out under normal circumstances. But stimuli can pop out because of priming[6]. For example, if you spend a lot of time reading fantasy with orcs and goblins and dragons, your attention is biased to recognize fantasy elements like swords, long terrains, castles, etc. Because of the priming (past influence), seemingly neutral stimuli become more salient and become distractions.

So…..

The question is not if we are losing attention, the question is – why is it hard to focus?

Focus = Attention + Memory + Commitment to goal + Resisting distraction

Now let’s see how focus is about emotions, engagement, and skills.

Handling emotions

I’ll use this stimulus prioritization framework to explain what breaks our focus. Emotions affect our behavior to either approach, avoid, or be neutral toward a stimulus. A task that creates negative emotions like frustration trigger avoidance behavior. A task that creates positive emotions like joy trigger approach behavior. A task that creates no emotions leads to a neutral response like working on autopilot or being indifferent.

There is a core assumption – all sorts of work will trigger neutral, positive, and negative emotions. For focus to stay for a long time, one has to tolerate all those emotions. This means a person has to have emotional regulation to work with the negative emotions and not let them trigger avoidance behavior.

You would lose focus the moment a more rewarding thing comes up or the task you are doing creates a negative feeling which you want to get rid of.

Engagement: Rewards you get from work

Let’s look back at how focus on Instagram stays. Classic behavioral studies by B.F. Skinner[7] have shown that an animal will engage with a task and do it as much as possible if there is a high chance of pseudo-random rewards at pseudo-random times. This is formally called the variable ratio schedule of reinforcement with variable reward magnitudes.

Let’s unpack that. It simply means we will perform an action frequently if we know there is a reward for it. The reward is the positive emotion you get by scrolling through reels. It is the positive feeling of sending your bestie a reel. But if the reward is unpredictable (very good reward, ok reward, good enough reward) and it occurs at unexpected times (random notifications, scrolling through a page, etc.), we tend to maximize the behavior of using Instagram to maximize the reward we get. It’s like gambling – gamblers gamble a lot to maximize their overall chances of a reward.

Consider your ability to focus for a work task or during a meeting a complex behavior. A very simple human behavior principle applies to it. A behavior that earns a reward continues. A behavior that earns a punishment or earns nothing fades away. This principle of reinforcement guides most of our everyday actions that turn into habits. Once a behavior has graduated to a habit, the reward and punishment doesn’t matter as much. For example, let’s say that you had multiple bad meetings over a year, you start avoiding them. Even though you get better at doing these meetings, avoiding meetings could become a habit. Your brain will then automatically nudge you to bring your focus away from meetings.

If a task is not rewarding, and it is just plain neutral, we call it boring and unstimulating. This is when attention moves from focusing on the outside world to focusing on your own thoughts. This leads to mind-wandering, negative thoughts, and sometimes, creative insights.

Engagement: Multi-tasking

Doing things in parallel improves motivation and efficiency if at least one of the tasks is very boring or automatic. 2 cognitively demanding tasks back to back or in parallel will fatigue the brain.

The real problem is over-tasking, which is taking on too much on your plate at a time because emotions are saying you can. Emotions don’t always remain the same as the tasks progress, and this changes your efficiency and motivation.

Decision criteria to multi-task, all validated with published research. Source: Don’t just trust me bro.

Multitask if:

- At least 1 task is boring or repetitive.

- At least 1 task is demotivating.

- Light music or music that puts you in flow is your 2nd task.

- You are prone to making errors if you keep zoning out.

- Your parallel task is light browsing, light chatting, light co-working.

Don’t multitask if:

- Both tasks require high attention.

- Both tasks interfere with each other because both are text-based or both are numerical or both are visual design.

- Both tasks are novel or very difficult.

The rules apply to most, but exceptions exist.

Skills

The idea with skills is that your level of skill affects how much mental work you have to do to perform it. Experts and experienced people are good at what they do. When the brain has done a task over and over again, it becomes a habit. It goes on autopilot. The task feels easy and effortless for them. On the contrary, for novices and freshers, complicated tasks can be exciting but the lack of familiarity with those tasks dramatically increase mental effort. For many, doing the tasks fatigues the brain. Neuroimaging studies[8] have confirmed this – tasks you have practiced a lot have lesser activity in the cortical regions of the brain that govern our executive functions like processing, thinking, decision-making, analysis, etc. These areas are most engaged when a task is new. More cortical activity is subjectively interpreted as “lots of mental effort”.

This is why many novices find certain tasks exhausting but pros do not. The novices have a lot of cortical activity going on that creates mental exhaustion. The pros do the tasks at a habit-level, so it doesn’t take up mental resources.

And, this fatigue is like the negative emotion that triggers avoidance behavior. By stopping the task and getting distracted, the brain stops getting fatigued. So losing focus becomes a coping mechanism for mentally demanding tasks.

The key takeaway here is not figuring out why we lose focus – it is – building a skill lets you do tasks more easily and effortlessly, so focus doesn’t go away.

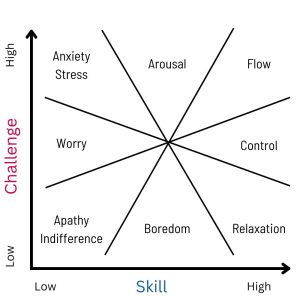

But I’ve simplified the relationship between skill and focus. We need a more detailed look at it and it comes from the experience fluctuation chart made by Mihaly Csiksentmihalyi.

Effect of mood: Experience fluctuation chart

Consider only 2 variables. The difficulty of your task (the challenge) and your overall skills to handle the task (your skill). Researchers have shown that the 2 variables create 8 different moods, including feeling flow, excitement, stress, and boredom. All 8 of them are different levels of focus. Flow, arousal, and control are good for focus. But boredom, indifference, relaxation, worry, and anxiety are not.

What happens when you have relaxation, boredom, indifference, worry, and anxiety? These are all emotions that lead to neutral or avoidance behaviors. To tolerate them, you need to either multi-task with to increase the stimulation of the work you are doing or manage your emotions.

Flow is considered the epitome of focus – and it occurs when you are skilled enough to just handle the task at hand. The mismatch between your skill and the work demand should be minimal, but the demand should be slightly higher (aka mildly challenging).

How do you restore your ability to focus?

When fatigue sets in due to a high amount of negative emotions like stress and not liking what you do or feeling incapable of doing your work, that fatigue has to go down. Researchers have identified 4 features of different types of breaks that restore attention (or more precisely, restore the ability handle the stress of paying attention).

A well-established theory called the “attention restoration theory[9]” says that our capacity to focus on a task reduces as we get exhausted. After exhaustion, we reach the “directed attention fatigue” state which weakens cognitive abilities (thinking, memory accuracy, etc.) and emotional management (dealing with stress). To come out of attention fatigue and restore the ability to focus, one has to immerse themselves in restorative breaks. And they should meet at least 1 of 4 conditions: Fascination, Distance, Extended engagement, and Psychological compatibility.

- Fascination is when a person is motivated to engage in something without feeling any effort (like looking at a new gadget).

- Distance is physical and psychological separation from work (like leaving the room and staring into the roads).

- Extended engagement describes breaks/environments that occupy the mind enough to keep it engaged (like a game of chess).

- Psychological compatibility is a break that aligns with one’s interests or tendencies (like something you find fun and interesting).

So for most people simply stepping away from work and engaging in a fun activity is enough to restore attention.

Typical types of breaks that improve our ability to focus:

- Simple social media distractions like memes, reels, and YouTube shorts

- Lunch and snack breaks with mundane or non-work conversations

- Short moments of gaming with coworkers or phone calls with friends

- Evening plans like dates, exercise, sports, or movies

- Weekend getaways in natural environments

- Long vacations

I further classify these breaks into 2 simple formats:

- Leisure breaks: Hobbies, social time, vacations, adventure, movies, binge-watching. These breaks typically take money and effort. They make extra-hard work tolerable. These restore emotions and meaning in life.

- Recovery breaks: Sleep, exercise, idle time, no calls/texts, screen-free time. These breaks take almost no money and effort. They make the brain capable of braining. These restore your biological functioning.

Takeaway

Consider your emotional responses to work, whether you feel rewarded, the engagement level of the task, and your skill level to assess why you lose focus for some tasks but have it for other tasks.

Sources

[2]: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26386145

[3]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn755

[4]: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00218/full

[5]: https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/advan.00109.2016?rss=1

[6]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/bf03209251

[7]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1959-07839-001

[8]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16242923/

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666957920300069

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.