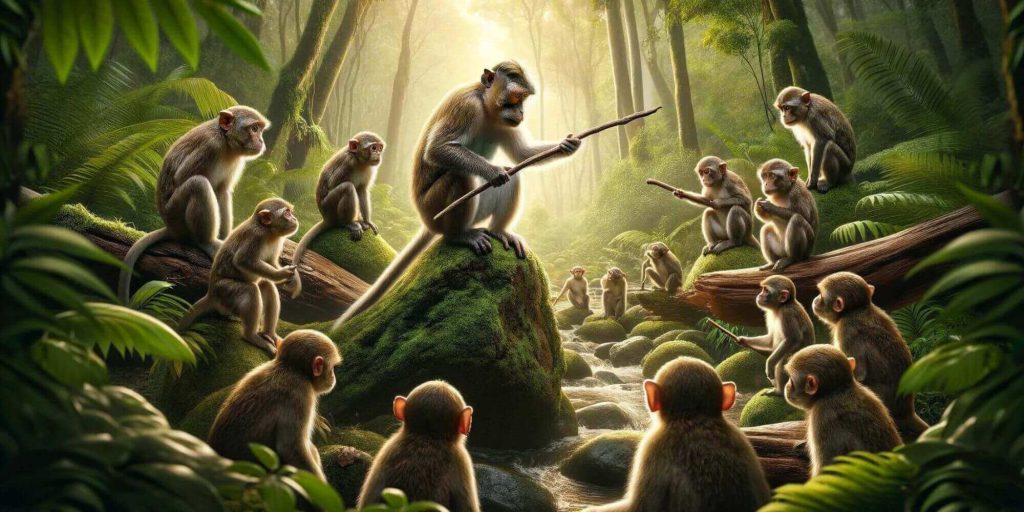

Monkey see, monkey do. We aren’t just monkeys, but a learning technique they used – learning by observation – still is one of the most powerful techniques we’ve developed through evolution.

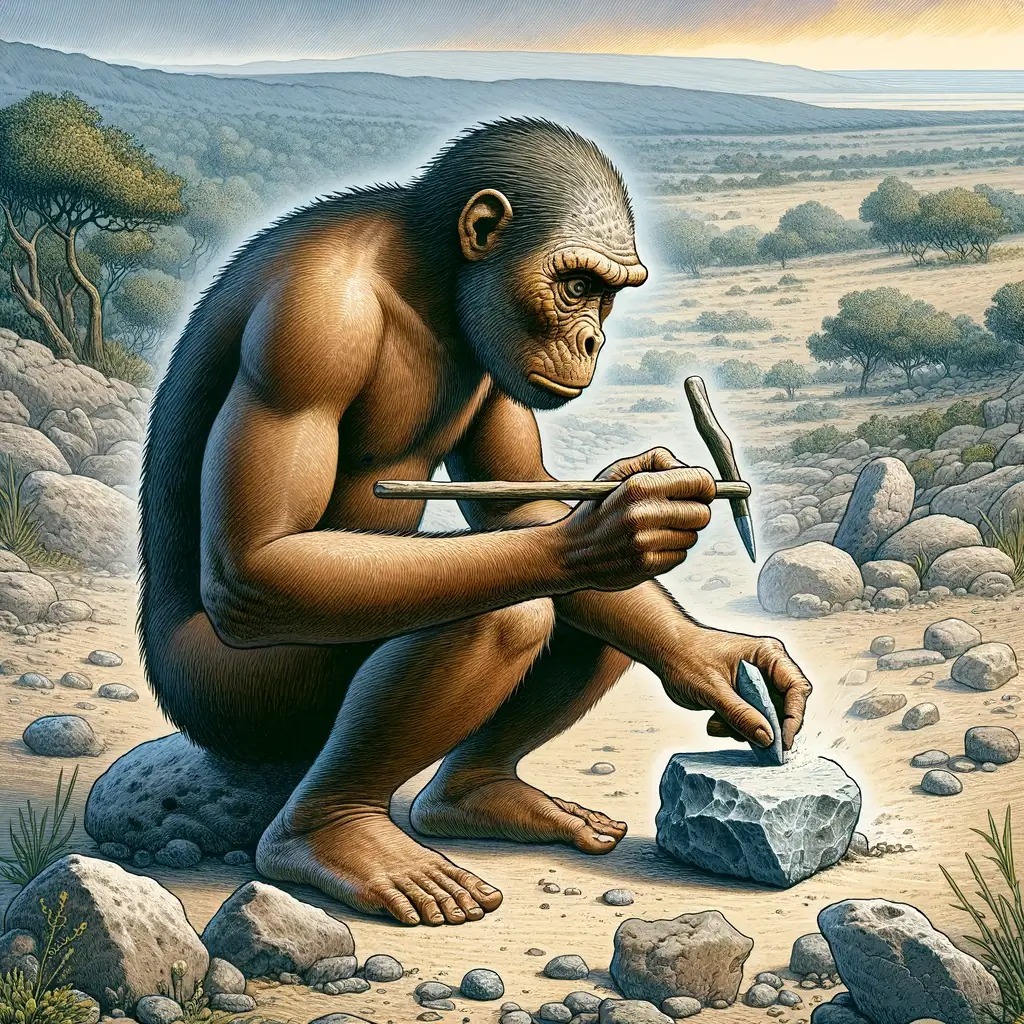

The story goes… Apes 1.6 million years ago observed other apes sharpening stones and sticks. Other apes followed and they became great hunters & builders with their tool-making. There were no instructional manuals. No technologies. And almost certainly no verbal communication apart from basic primal sounds. Apes copied other apes. Younglings mimicked the elders. The first moments of advanced learning emerged from “observation” at the dawn of the tool-making age – the Stone Age.

For those more interested in these apes – I’m talking about the Homo Habilis[1] (the early humans) who lived around 2.5 million years to 1.5 million years ago, born out of Africa, and potentially died out before migrating to East Asia. These 4-foot-tall ape-resembling 30 kg hominins with long arms, opposable thumbs, and short legs[2] are some of the first skilled stone and bone[3] tool users. A few of them made tools (the Knappers, call them the first engineers) and others used them. Others saw how tools are made and used, and they copied it. Although, the earliest tools (sharpened rocks) date up to 3.3 million years ago[4], the Homo Habilis tools (1.8 mya) were more refined – sharp stones carved out of particular rocks and rocks made into spheres – to cut animal skin and meat, crush bone, and cut plants. They are also known to stack rocks as support for stick pillars, which probably held an animal skin roof or created a windbreak.

The first 8 minutes of 2001: A Space Odyssey shows this but with a sci-fi twist.

This story is simple and possibly not even the first instance of learning by copying. Fast forward to our modern understanding of observational learning…

Learning by observing is a powerful way for people to acquire new behaviors, skills, and attitudes. Share on XObservational learning

Early psychologists, most notably Albert Bandura, from the behaviorism era, drew a border around the concept of learning as per what’s seen and observable instead of theorizing a process taking place inside the brain. For this article, I’ll stick to that approach.

Actions, approaches, words and sentences, processes, decisions, etc., are all behaviors here.

Bandura coined the term “observational learning,” which is a method of acquiring someone else’s behavior by simply observing and mimicking it. This type of learning is also called “behavioral modeling,” when it is done more deliberately. The model is the person who has the behavior and demonstrates it precisely. Learners are expected to process it and mimic it. Behavioral modeling helps people acquire an observable way of doing something, an emotional response, and an attitude seen through body language, actions, and words.

For example,

- Observable way of doing something: Dance movements, turning the light switch on and off.

- Emotional response: Shouting when someone upsets you, smiling after extended eye contact.

- Attitude: Judging something good or bad as per the role model’s judgment, warmth of greeting others during small talk.

Most early instances of language learning are purely behavioral modeling. Children acquire words by imitating the sounds parents make while pointing at objects. Diagrams that depict action aim to teach via behavior modeling as adults too. Instructions in bathrooms, tutorials showing how to brush teeth correctly, etc., all leverage behavioral modeling. Observational learning is a broad category of learning that includes behavioral modeling.

Bandura created the ARRM framework to describe how observational learning occurs by observing a “model”, specifically in the context of social learning – how people learn anything (actions, thought processes, expectations, decisions, skills, concepts, etc.) from others.

ARRM stands for Attention, Retention, Reproduction, and Motivation.

- Attention: The behavior that needs to be learned must be observable.

- Retention: The observable behavior should create a memory of what it is.

- Reproduction: The learner must be able to imitate the behavior.

- Motivation: The learner must have a reason to learn that behavior, usually by seeing how it has positive consequences or how it avoids negative consequences.

For this framework to help in complex learning[5], people have to first symbolically “code” what is being learned via attention. That is, a person keenly observes others, analyzes their actions, and then represents the learning in their head using some logic and procedure. Usually, the procedure is verbal (how-to summary), visual (movement), or numerical (order of steps).

Consider this – a person is demonstrating how to pour water from a filled glass into an empty glass from 1-meter height. This involves proper placement of hands and turning the filled glass. Then it involves shifting the filled glass position so water falls directly into the empty glass based on the water’s flow angle. All of this can be converted into steps. The learner must “code” the steps through analysis, and then mimic it based on the coded “steps.” This way, learning lasts much longer. In short, the learner MUST conceptualize what is being taught for it to last in the learner’s memory.

Strength of observational learning

A basic principle of learning is a behavior that has negative consequences reduces and a behavior that is rewarded increases. Action, approach, words, processes, decisions, etc., are all behaviors here.

But the funky thing about monkey see monkey do is you don’t have to be rewarded or punished. You just have to observe others being rewarded or punished. If they are rewarded, you adopt it. If they are punished, you don’t adopt them.

Learning through behavioral modeling goes beyond just imitation. When we see a person getting rewarded for being well-dressed, we may observe the behavior and mimic it for a similar reward. This is vicarious reinforcement. When we see a behavior being rewarded, we are more likely to imitate it. When we see a behavior being punished, we are less likely to imitate it, just to avoid that potential punishment. This shows the power of role models in a context. When role models are being rewarded, we are likely to emulate them. When role models get punished or fail, we are likely to reject that action.

We’ve seen this in research. Aggression is acquired by an observer[6] if they see aggression getting rewarded. Students become more attentive[7] if their peers are rewarded for being attentive. Adults are likely to adopt a problem-solving mindset[8] to reduce their stress if they see others reducing their stress via problem-solving methods.

These role models typically appear as parents and early teachers. But, other experts, our peers, TV actors, fictional characters, etc., become role models. You may even spot this in everyday conversation – Harry Potter had friends to win against the dark lord, even though he wasn’t as powerful as the dark lord by himself. The observational learning here would – friends can help you win against difficult odds.

From the modern marketing terminology point of view, this is a core principle of “social proof“. When we see others do something with a desirable consequence, we are more likely to do it. Salespeople often pitch, “2000 customers already love this, you will too.” An Instagram post has 19k likes, and we are likely to watch it without reading anything else.

The consequence of a behavior, which gets observed, becomes a heuristic for us to adopt that behavior. Suppose you are driving a car and there is a fork ahead. You see a lot of people go left instead of right. Both roads lead to the same destination. The right road is moving slowly and appears to be stuck in a jam. The left road is more crowded but everyone is moving at a steady pace. As the driver, you will immediately learn that the consequence of going left is better. But you’ll base this judgment on 1 single fact – the traffic is not in a jam. That is your heuristic – the shortcut to your analysis. And, you will acquire new learning which tells you going into a more crowded but moving lane has better consequences than going on an emptier road with a traffic jam.

The strength of vicarious reinforcement also increases as per the size of social proof. More people choosing something = more likely to imitate them. This is how we choose which restaurants are better.

There is a powerful authority effect too. The strength of vicarious reinforcement will also increase if behavior is shown by someone in authority – exercise tips from a fitness influencer, cooking tips from a chef, recording tips from a musician, etc. Higher the authority, the easier it is to imitate it for a positive consequence. Sometimes, this overrides social proof. You can have 1 expert say, “Do this,” and 10 non-experts say “Do that.” We are likely to listen to the expert. But this gets complicated because of other aspects of the environment and our thought processes.

Suppose the expert is talking about making local food. But, the expert is not native to the land. This will make you doubt the expert’s relevance. Suppose you also think non-experts are doing something a different way because they have access to knowledge the expert doesn’t have. Then you may start thinking about what that information is, and you conclude it’s the local pricing of ingredients.

All of these factors affect one final thing – do you listen to the expert or the non-expert? We tend to imitate behavior by just observing, but it also depends on the context and our thought processes. This principle is known as triadic reciprocal causation[9] – The environment, the observation, and our thought processes affect each other before we learn something.

How observational learning (behavioral modeling) is applied to the world

- Education: Students learn by imitating the teacher.

- Work: Adults emulate their bosses who get rewarded. Adults emulate their coworkers who get rewarded.

- Consumerism: People buy what other people are buying.

- Social acceptance: Behavior that is punished is considered bad behavior (jumping the traffic signal).

Since this article is about education, I’ll create a few templates for using observational learning for education for specific purposes.

Teacher’s Takeaway: Observational learning templates

For teachers teaching English: Have a likable person demonstrate how to say something and ask students to mimic that.

For teachers teaching Math: Praise other students for practice instead of correct answers to encourage others to practice.

For coaches training physical education: Don’t just coach, teach by doing and explain your actions so students imitate.

For teachers teaching history: Ask students to emulate a historical conflict for the rest of the class. Then ask another set of students to emulate the other students. Continue till everyone has observed and demo-ed the conflict.

For teachers teaching computer programming: Write the program or function once and walk through your thought process for students to mimic you.

For teachers planning their classes: Make a list of acceptable rewards and punishments and list them in tiers of strength. Use them to reward or punish students. Make the list public, so the students are aware of the consequences of their actions.

For teachers encouraging classroom cohesion or diversity: When assigning rewards, highlight what precise aspect is being rewarded – whether it is the uniqueness of a student or conformity to school rules. This way, students know what behavior to observe and learn.

For teachers teaching social norms or cultural rules: Demonstrate a scenario of how people greet or stand or behave at a dinner table. Ask students to imitate it.

For teachers discussing sensitive topics like sex-ed or aggression: Use dummy models or pictures that symbolically make students understand what is acceptable behavior or not.

Sources

[2]: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/homo-habilis-early-maker-stone-tools.html

[3]: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.8079169

[4]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14464

[5]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1973-24221-001

[6]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1964-05761-001

[7]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1901/jaba.1973.6-71

[8]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/JRPL.142.4.413-426

[9]: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ983778.pdf

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.