Procrastination – regretfully delaying tasks you need to complete – is a common problem in anxiety[1], depression[2], ADHD[3], and personality disorders[4], and it worsens with severe stress[5], perfectionism[6], low self-esteem[7] (negative attitude toward oneself), sleep deprivation, and low self-efficacy[8] (confidence in ability and skill). It’s a universal problem because anxiety and mismanaging emotions[9] are the 2 cores of many emotion-related psychological disturbances. Especially anxiety due to a lack of emotional regulation about work demands, personal and social stress, etc.

Stress-induced rise in cortisol level (stress hormone) can shift behavior from goal-oriented to more habitual actions[10], particularly in people who are highly reactive to stress (e.g., respond very strongly with emotions during a difficulty, the nervous system responds strongly to minor stress, etc.). And if an anxious response is your habit, procrastination amplifies by the tailwind caused by anxiety. So, feeling the burden of stress steers people away from their goals and they resort to their default habits.

At its core, procrastination is an emotion-regulation problem; rather, a failure to regulate emotions. I wrote an article a few years ago explaining how procrastination is a response to some anxiety about doing the task or anxiety about what happens after doing it. (it is perhaps my most successful article, which procrastinators procrastinated on reading because it is long XD). Fear of failure, feeling “if it’s not perfect, it’s worthless”, guilt, feeling incompetent, etc., are anxieties that create procrastination.

A very simple mechanism enables procrastination. It’s about the rewards & pain. Behavior that gets you a reward continues and behavior that gets you a pain discontinues. This is one of the most fundamental rules of animal behavior – operant conditioning.

When anxiety triggers procrastination and you put off a task, you seek a mood-uplifting activity to repair your mood. This is the reward. So you continue procrastination to get that reward. When you tolerate that anxiety and start working against every bone’s wish in your body, you feel the stress of the work. That’s the pain caused by doing the right thing. So you end up procrastinating to avoid the pain. This is the “maintenance” cycle. That’s why, dealing with anxiety helps – it reduces the need to seek a reward (aka your dopamine hit) from distracting activities.

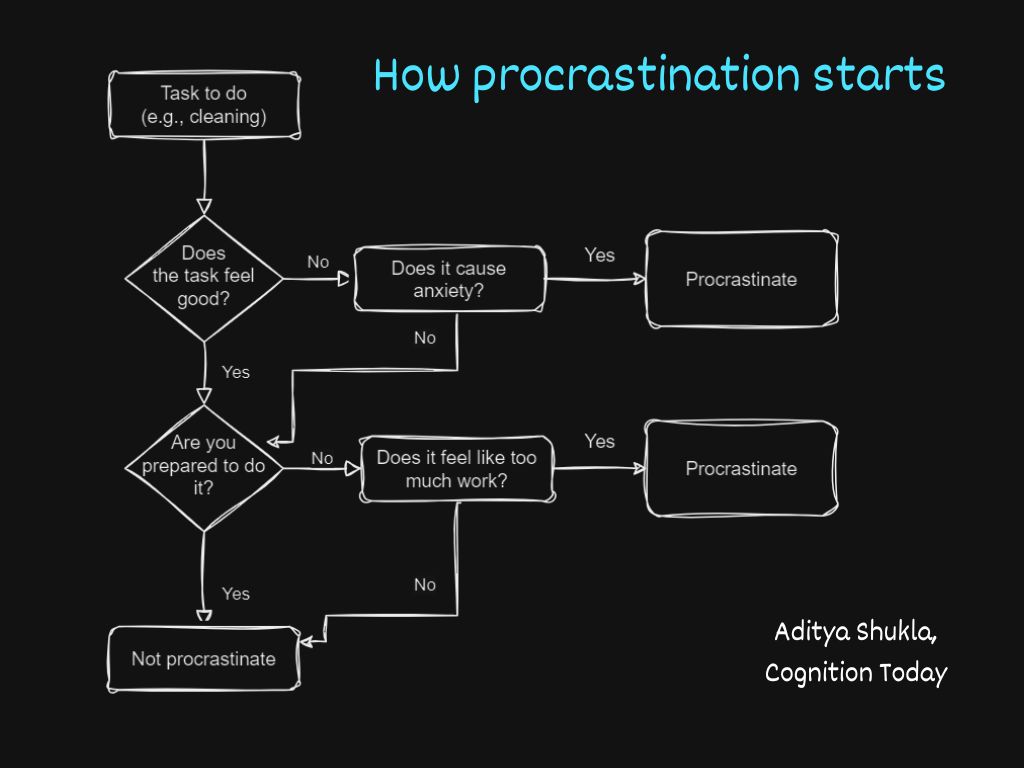

For your own introspection, the flow chart below should help you conceptualize your decision-making before procrastination.

So without more explanation, let’s focus on the anxiety and what you can do about it.

- 1. Focus on the process and not the outcome

- 2. Get psychologically and physically close to your task and make it tangible

- 3. Improve sleep quality

- 4. Cultivate supportive habits

- 5. Build resilience and tolerance for negative emotions

- 6. Practice self-forgiveness

- 7. Use practical techniques like Chunking and Pomodoro technique

- Sources

1. Focus on the process and not the outcome

It is more useful to focus on the process[11] and not the end goal because the process is ongoing work, so it doesn’t create as much anxiety as imagining the outcome. Adopting a “process-focused” approach as opposed to an “outcome-focused” approach reduces procrastination. Instead of focusing on your goal (E.g., writing an exam), if you focus on the process (E.g., engaging in the study material and absorbing it), you’ll procrastinate less. This is because procrastination is the result of anxiety associated with the outcome of a task. A process focus is linked to reduced fear of failure and lesser task aversion. A process focus also helps in planning your work which could be an effective way to manage time, stress, and milestones – make your lists, roadmaps, not-to-do-lists, excel sheets, etc., and begin the process.

Focusing on the process helps with exercise procrastination too. In a study[12], researchers tracked progress, procrastination, and feelings about exercising during an 8-week high-intensity interval training program under 2 conditions: Participants either focused on the exercise journey or they focused on the outcome (e.g., higher strength). Those who focused on the process were more likely to work out and stick to the program. But those focusing on the goal also showed objective performance gains.

Takeaway: Engage yourself in the process instead of the end goal

2. Get psychologically and physically close to your task and make it tangible

Bring the avoided/procrastinated task closer to you and distance the distracting activities you do while procrastinating. You can do this in 2 ways:

- By assigning more value/meaning to the avoided task and belittling the distraction activity.

- Modifying your environment to have easier access to completing your tasks – removing distractions (deleting social apps, eating before the task) AND setting up the basics of doing a task (like making the document, marking the calendar, etc.)

In short: Make the task easy, clearly define it, & assign it urgency.

For example, if you procrastinate paying bills in spite of having money, make sure you are logged into paying portals and the process of paying is easy. Behaviors like not remembering a password or account details are unnecessary hindrances. The construal level theory of psychological distance predicts (and research verifies[13]) that thinking about a task in more concrete terms and bringing it closer to yourself in time (now vs. future) can decrease the chances of procrastination. Abstract & vague goals won’t always work, make them real and tangible. That’ll allow your brain to accept the goals more readily. For this to happen, identify all the steps in your tasks, break them down into smaller pieces, and set an immediate deadline for it (tonight instead of end-of-week).

Some goals are ambiguous and they are often more difficult to stick to. Researchers observed[14] procrastination on ambiguous goals and found immediate ambiguous goals reduce motivation. If the goal is immediate, then it increases motivation when it is clearly defined. Making the goal clear is like psychologically getting close to it.

Takeaway: Define your task well. Begin with the task immediately instead of thinking about completing it. Just the first step now.

3. Improve sleep quality

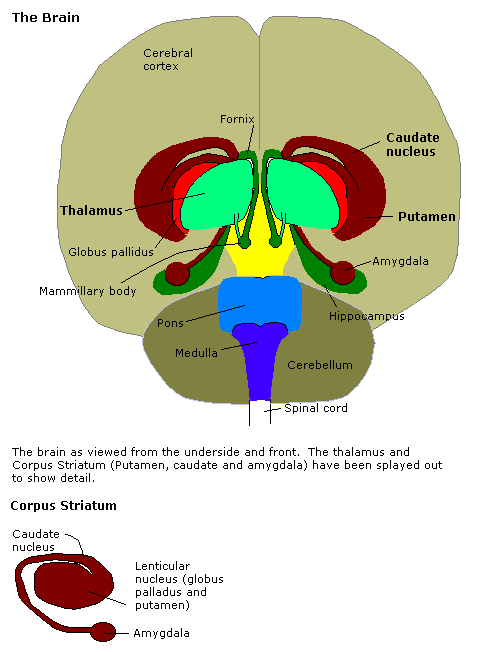

One function of sleep is to dilute emotions and make them more manageable. When you are sleep-deprived, for a day, or even chronically, the amygdala functions poorly. It is the brain region that processes emotions. It has 3 important functions in getting rid of procrastination thoughts – amygdala reactivity, amygdala up-regulation, and amygdala down-regulation.

High amygdala reactivity can make a person sensitive and more prone to negative thoughts (aka anxiety, which leads to procrastination). Amygdala upregulation can make a person’s emotions more intense and rigid. Now, sleep reduces amygdala reactivity and downregulates it[15]. That means sleep deprivation makes your emotions go out of control. Fun fact, disturbed sleep and lack of REM sleep can make you feel more embarrassed about something[16] you did the previous day. And being embarrassed generally means feeling motivated to AVOID something.

Image: Original uploader of gif version was RobinH at en.wikibooks, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/[17], via Wikimedia Commons

Related: Bad sleep might make you procrastinate

Takeaway: Improve your sleep hygiene so your brain can automatically plan your work as it is the sleep’s default function and also keep your emotions in check.

4. Cultivate supportive habits

Depending on the severity of your procrastination and anxiety, you might need to put in some additional effort to cultivate new habits that act as your default state – finishing your morning routine quickly, having food at fixed times, keeping your devices charged, ensuring your documents are well organized, etc.

People resort to habits when they are stressed[18] and are in an emotional state. To overcome procrastination after stress, you will most likely default to your habits. So the idea is to default to habits that help, not habits that hurt. This means you have to cultivate certain habits by doing them repeatedly when you are not stressed. Routines are the best example of this. If you are delaying an email, develop the habit of responding to normal emails as quickly as possible.

As a response to stress, people begin their mood-repairing and distraction activities – anything to delay the work that causes stress. Researchers call this dilatory behavior – like a pointless set of activities whose goal is to solely delay a task. Like bureaucratic form-filling, mindless cleaning, etc. (more relatable examples here). The real support comes from dilatory habits that themselves are useful – like organizing your devices and work documents, clearly naming files, keeping devices charged, doing a relaxing hobby, etc.

The obvious trick to making something a habit is to repeat it regularly at a fixed time or after a fixed moment.

Takeaway: Develop productive habits on insignificant days so you default to those habits when you are anxious.

5. Build resilience and tolerance for negative emotions

Resilience is the ability to bounce back from stressful events and resist damage. It is a personal factor that holds you strong in the presence of difficulty. Procrastination, in this case, means not being resilient in the face of the pain you think your task will give you.

Use the emotional self-regulation strategy recommended in Berking and Whitley’s book[19] which verifiably decreases procrastination.

- Choose the task you procrastinate.

- Bring aversive and negative emotions & thoughts associated with the task into awareness.

- Instruct yourself to tolerate those negative emotions – boredom, fear of failure, fear of judgment, feelings of incompetence, etc.

- Regulate them with these steps:

- Begin with allowing those emotions to exist. Do not suppress them.

- Then tell yourself that you are strong, tough, and resilient (ability to adjust to harsh circumstances and bounce back).

- Finally, ascribe more emotional meaning to the task and emotionally commit to that task. Find justifications why you should do the task.

Takeaway: Build mental tolerance for discomfort and negative emotions.

6. Practice self-forgiveness

Forgive yourself for the times you’ve procrastinated on a specific task in the past and suffered through guilt, stress, and anxiety. According to the paper[20] that gives us this incredibly easy strategy, self-forgiveness reduces negative emotions about oneself, and that reduces the likelihood of procrastinating the same activity again. So if you procrastinate a medical appointment once, forgive yourself for delaying it. The second time might not occur. Self-forgiveness can also convert to self-compassion. This reduces blaming yourself + guilt about procrastination. The logic here is people who show self-love are likely to deal with stress better. So by default, they are in a better condition to show self-care. This matters a lot[21] in life-changing stressful situations like coping with a disease or injury. Be kind to yourself when things get overwhelming.

Procrastinators know this well – the act of delaying a task creates guilt, which further stresses you out, and you withdraw completely. You may even trivialize the task by saying, “F*ck it, not gonna do it.” This is when self-forgiveness helps – there is no need to judge yourself harshly for not doing a task. When you realize you feel guilty, begin the task in whatever capacity you can.

Takeaway: Self-forgiveness will reduce the guilt of delaying tasks.

7. Use practical techniques like Chunking and Pomodoro technique

Chunking: Chunking is grouping things together based on similarity or urgency. Of all the tasks you have to do, group the similar or urgent ones together.

What this does is – the emotional burden of each task in a chunk now applies to the whole chunk without much amplification. You can then rationalize a chunk of 4 tasks as – the same level of anxiety now gets 4 tasks done instead of doing that level of anxiety 4 times over the next week. Chunking also lets you progress on your work with a “mental set”. Every task comes with a mental set which is a set of resources the brain liquifies to get that task done. When the same resources apply to more tasks, the tasks feel easier because the resources are already on standby (think of the resources as your pit crew and the laps in an F1 race as your chunks).

Stress makes us simplify information[22]. This helps us when we are overburdened with tasks. Instead of fully avoiding work under high stress, it might be useful to let the brain do its automatic simplification.

Pomodoro technique: Use the popular Pomodoro technique to gain control over your tasks and relieve the pressure from some associated anxiety. The Pomodoro technique is structured time management that uses blocks of time spaced by breaks in a group of 3 blocks of time. This changes the concept of time from ‘how much time is needed’ to ‘what I can accomplish in 20 minutes.’ The approach is called “effort regulation”. This cognitive change facilitates task completion and focus and increases motivation[23]. Follow the next steps to implement the Pomodoro technique:

- Set a timer to 20-25 minutes (block 1 starts)

- Spend 20-25 minutes on a task

- Once the timer rings, stop.

- Take a break of 5 minutes (Block 1 ends)

- Repeat for 3-4 cycles of these blocks.

Takeway: Use a structured method to do your tasks which reduce the emotional burden of those tasks. Do similar tasks together (chunking), take systematic breaks after a short burst of work (Pomodoro technique).

Baby steps, right? I hope these insights help you reduce procrastination!

Main takeaway: You can overcome procrastination with a habit of regulating your emotions about your work.

Sources

[2]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10942-016-0235-1

[3]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07448481.2019.1626399

[4]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-023-04815-7

[5]: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/6/5031

[6]: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/14/5099

[7]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0191886994901406

[8]: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sumaira-Khurshid/publication/327252993_Academic_Procrastination_as_a_Product_of_Low_Self-Esteem_A_Mediational_Role_of_Academic_Self-Efficay/links/5b975ed392851c78c41b46fe/Academic-Procrastination-as-a-Product-of-Low-Self-Esteem-A-Mediational-Role-of-Academic-Self-Efficay.pdf

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0005789407000202

[10]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278262618300460

[11]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11031-016-9541-2

[12]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jasp.12646

[13]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02240.x

[14]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ejsp.2541

[15]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3747835/

[16]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982219307614

[17]: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166432811000258

[19]: https://www.springer.com/in/book/9781493910212

[20]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886910000474

[21]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15298868.2011.558404

[22]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02699939108411030

[23]: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjep.12593

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.

So well put together and relevant. Thank you.

Thank you for appreciating it Elizabeth 🙂