One may wonder if they should start therapy when they feel they need psychological help. Although therapy generally helps most people, it has a downside for some people. Much research shows therapy can be less helpful or even detrimental to some clients, while money, self-help, placebos, and medication can be more helpful in solving well-being and quality of life problems. To manage stress, adjust, and overcome negative thoughts, anxiety, and depression, nothing is wrong with choosing no therapy over therapy because a person’s motivation and receptibility can affect the quality of therapy. But in the case of severe illnesses like OCD[1], schizophrenia[2], and bipolar disorder[3], specifically targeted therapies and medication prove more useful than no therapy. In short, to improve well-being and quality of life, you might not need therapy. To deal with severe problems, therapy might be a good idea.

Regardless of the choice one makes on how to approach their mental health, I’ll discuss the reasons therapy fails.

- What happens in therapy?

- 1. Therapy has negative side effects, fails to help in recovery, and can make things worse

- 2. Clients drop out and end the process too early to benefit from therapy

- 3. Too many therapies exist, and we can’t pinpoint the helpful ingredient in therapy

- 4. Therapy might be a placebo, but placebos are potent healers

- 5. Medication (along with therapy/placebo) could be a more convenient alternative

- 6. More money can solve problems that people try to solve with therapy

- 7. Bad research leads to bad therapeutic insights

- Sources

What happens in therapy?

Psychotherapy, or therapy, is a conversational and behavioral commitment to yourself and a service provider to improve your mental health. For a client, it lasts 4-20 sessions across weeks or months, with typical sessions taking 45 minutes to 1 hour. A client commits to efforts like homework, recovery from the intense session, re-adjusting to life, making therapeutic changes, and preparation for the next session.

What therapy typically involves: education about mental health, psychology, and neuroscience, learning and practicing relaxation techniques like breathing, muscle relaxation, meditation, and mindfulness, conversations about a client’s concerns, activities to reframe thoughts, activities to change responses like fear and anxiety to specific triggers, learning life skills, setting goals, creating a safe space to talk about problems, etc.

Practical concerns: Therapy can cost a large chunk of monthly income to most. And insurance-enabled therapists can have long waitlists. It may cost anywhere between $100 to $200 per session in the US and Rs. 500 to 2500 in India. Insurance may not give you enough coverage to afford therapy. Some therapists don’t work in well-regulated regions which enforce strict licensing rules or work in a non-inclusive society. Some aren’t equipped to solve your problems and aren’t ethical in their practice. So many seek alternative help like friends, family, spiritual gurus, or astrology to get some form of therapy/help. And sometimes, people choose counseling – which is a guided conversation with a trained professional to solve specific problems, seek advice, and freely speak about specific issues in a respectful, empathetic way. In a way, counseling is a micro-therapy session without the long commitment to a therapeutic relationship with a licensed professional.

Do you need to spend the time, effort, and money, and commit to therapy for your well-being? Is the outcome worth it? The answer is Yesn’t.

1. Therapy has negative side effects, fails to help in recovery, and can make things worse

Michael Linden and Marie-Luise Schermuly-Haupt[4], in their 2014 paper, conclude that 5-20% of those who enter therapy have negative side effects like worsening symptoms, new symptoms, future relapse, suicidality, social and occupational problems, dependence on therapy for normal functioning, lack of confidence in self-management, etc. And these side effects depend on how suggestible a person is, the nature of therapy, failure of therapy, severity of problems, client’s expectations, etc. For example, in psychodynamic therapies that often involve getting to repressed memories, revealing and re-processing past trauma can make one feel worse than they did before exploring those traumas.

Why side effects occur

In an extensive global analysis reported in a 2019 paper[5], researchers say about 5-8% of people have long-term and short-term negative effects from therapy, and about 40-60% of people don’t reach the pre-established “recovery” criterion. Some key reasons why therapy makes it worse for the client are – Misuse of the therapist’s power, boundary violations, wrong use of a technique, a cultural mismatch between client and therapist, therapist’s errors, client’s expectations being unmet, undermining a client’s self-reliance, therapist’s rigidity and controlling behavior, lack of clear communication and problem-management about the course of therapy, and lack of therapy options. These problems make patients feel less competent during and after therapy, blamed, silenced, devalued, and disempowered. The study also reports that these issues are greatly misjudged by patients, researchers, and therapists. They don’t mutually agree on the severity of negative side effects or the problems associated with therapy.

The negative effects of therapy in their study have 8 themes:

- Contextual factors: Lack of access, cultural and social mismatch, political factors, lack of information

- Pre-therapy factors: No proper contract or consent-seeking, client’s negative expectations, bad timing, lack of acknowledging the client and focusing only on symptoms, past experience with therapy

- Therapist factors: Lack of skills, personal interests, financial interests, inflexibility, insufficient guidance, not understanding the problem

- Client factors: Lack of understanding, social/demographic problems, fear, helplessness

- Relationship processes: Mismatch between client and therapist, power dynamics, not listening to client’s preferences, unhealthy relationship patterns between client and therapist, dropouts, weak relationship, the therapist brings their personal issues in the therapy which influences their evaluation and judgment harming the relationship

- Therapist behaviors: Therapist makes errors, their personality affects problem-solving, improper use of skills, malpractice, client neglect, not addressing issues, poor self-control, blaming the client

- Therapy processes: Therapy doesn’t cater to the client’s needs, wrong formulation of a problem, wrong style of therapy for the problem, interference with other problems or aspects of healing like medication or risky behavior, therapy becomes harmful

- Endings: Abruptly ending therapy, therapy highlighting vulnerable memories and leaving the client disturbed without adequate support, improper termination of medication, and lack of follow up checks or not tieing loose ends

Each of these factors can affect each other in the larger context of healing and recovery and can also sequentially affect each other leading to bad “endings.”

Takeaway: There are many reasons why therapy can make mental health worse without giving you the ability to cope with its after-effects, so perhaps it isn’t the best first solution to overcome life’s problems.

2. Clients drop out and end the process too early to benefit from therapy

Clients drop out for many reasons and potentially fail to reach the promised recovery.

- They don’t like the therapist or their approach

- They got what they wanted or needed (via therapy or on their own)

- They are shopping around for the best option

- They feel worse or have side-effects

- The Client-Therapist relationship is unsafe or lacks mutual understanding and respect

- Weak therapeutic alliance (the beneficial relationship that is supposed to evolve between a therapist and client)

- Impulsive decisions

- They relapse and conclude therapy wasn’t useful

A 2009 study[6] suggests the average dropout rate is 35% across the 110 studies analyzed. A large 2012 study[7] looking at over 600 other studies estimates the rate is around 20% for adults. A 2018 study[8] looking at attrition in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) estimates the dropout rate is approximately 16%. A 2021 study[9] comparing in-person and teletherapy estimated similar dropout rates for both formats. Most rates were under 30% for short therapies (under 8 sessions) and under 35% for long therapies (8 or more sessions). Dropouts were also more common for therapists with lesser training.

Takeaway: If dropping out is likely to be a problem for an already weak solution, perhaps it is not the solution you need.

3. Too many therapies exist, and we can’t pinpoint the helpful ingredient in therapy

What therapy do you need? Who should be your therapist? Do you need therapy or something else? There are over 600 therapies and hundreds of alternatives like spirituality, Netflix, and astrology. A key issue is whether specific therapies like “CBT” or “mindfulness” have specific factors (like exercise, yoga, breathing routines, exposure to nature, movement, and new perspectives) in their approach that improve a client’s well-being or if all of these therapies have common factors (like a safe space, shifting attention to something new, expectations to improve, learning about new concepts in psychology and science, talking about problems to someone which allows self-reflection and unexpected insights, maintaining a discipline to deal with mental health, etc.) that improve wellbeing.

In the first case, the specifics of a particular therapy format might have some unique value that you might want from your own interest in therapy. In the second case, the specifics won’t matter at all, and all “therapies” have a common “therapiness” which acts as the secret sauce. Perhaps you can get your therapy in any way from whoever offers the common factors. Either way, research and more research and even more research cannot answer the question – is it the specifics of a therapy technique, some common ingredient in all therapies, or a mix of both that becomes the active ingredient in healing – we have no clue[10]. If the common factors contribute to well-being more than the specific factors, it would explain why people often feel spiritual gurus, friends, coaches, or even AI can be therapists in a very real, meaningful sense because they also can provide the same common factors. It also explains why therapy isn’t particularly helpful for many people even when other problems (the 8 themes above) don’t occur. If some specifics of therapy work, like exposure to difficult situations, exercise, exposure to nature, relaxation and discipline routines like yoga/meditation, and movements like dance or sports, why not just do them?

Takeaway: The non-specific factors of therapy can help you heal without entering therapy. Exercise, building trusted friendships, professional mentoring, group activities, hobbies under a tutor, etc., might help you for a lesser cost (time, money, effort) than therapy because they can also provide the “common factors” and the “specific factors” without a larger therapeutic context.

Is CBT the promised answer to mental health?

How effective is CBT? CBT is a collection of many techniques based on robust theories about behavior and less robust theories about cognition (how we perceive and make thoughts). It typically lasts for multiple sessions over a few weeks or months. CBT is effective[11] in treating some kinds of OCD, depression, and anxiety but not too good for PTSD or panic disorder. CBT does seem helpful for stress management too. One method called exposure therapy (systematically training a person to reduce the fear associated with a stimulus, for example) is more effective than other therapy techniques like cognitive restructuring. Another study[12] suggests CBT is mildly effective in preventing depression for up to a year.

For problems like ADHD, psychotherapy doesn’t seem all that useful[13] in managing symptoms like distractibility, inattention, unorganized lifestyle, etc. However, it can help manage some self-esteem and confidence problems and provide a reflective surface to discover solutions. Medication, on the other hand, does help those with ADHD.

CBT does seem useful for managing sleep problems, and one analysis of 27 studies[14] suggests it’s better than just improving sleep hygiene. Relaxation techniques are very powerful in improving sleep and they are often a part of CBT methods.

Considering the common factors and the ability to learn relaxation techniques on your own, is the whole therapy package worth it? Comparing CBT (or any therapy) with placebos can give some insight.

Therapy vs. Placebo vs. Medication vs. Money – Who wins?

4. Therapy might be a placebo, but placebos are potent healers

Some researchers say[15] that psychotherapy is partly a placebo – it works because of the “common factors” associated with therapy like the therapist’s motivation, the client’s expectations about improvement, awareness of healing strategies and unexpected reminders, etc., and not the specifics of therapy. Placebos are activities or objects that promise to help but don’t contain any active ingredient that causes a positive change. Placebos objectively improve something desirable. Sugar pills, rituals, sham activities, etc., are common placebos. A 2010 study[16] that analyzed many studies makes a daring claim that the benefits of psychotherapy are practically no better than the benefits of a placebo or control treatment for real patients. Essentially, going to therapy or doing something else that feels like it is going to help might be equally helpful. The “common factors” that are there in all forms of therapy or activities for healing might be enough to improve psychological wellbeing.

But placebos, by themselves, have added value when combined with non-placebo things like exercise or therapy. Having a placebo as an add-on[17]with exercise can improve cardio health and self-esteem, and increase positive emotions more than just exercising. A study comparing CBT with placebo and CBT without placebo[18] found that, even after 3 months, those receiving CBT + placebo had a lower depression score (which is good) and practiced relaxation techniques more often. The placebo in the study was taking 3 drops of sunflower oil daily for 10 minutes before doing prescribed relaxation exercises. The placebo was called “golden root oil,” described as a natural medicine with natural healing properties to tap into their inner strength and mobilize their bodies. Consider this – if a placebo like this oil can reduce depression long after therapy ends and sustains healthy behaviors that therapy itself couldn’t, is the therapy itself worth it?

Takeaway: Instead of therapy, you can easily choose a placebo or seemingly helpful thing such as sham activities, affirmations, hobbies, spiritual guidance, lifestyle ideas, friendly comfort, lifestyle healing products on the market, and motivational posts on Instagram to cope with stressful events that relieve temporary anxiety and depressive episodes.

5. Medication (along with therapy/placebo) could be a more convenient alternative

Medication in general[19], except for a few drugs, is more effective in treating social anxieties, overall anxiety, and panic disorder than a placebo and psychotherapy. In the same analysis, CBT was also marginally more effective than psychological placebo (sham healing/neutral/distracting activities) and pill placebo. Overall, most antidepressants[20] appear to relieve depressive symptoms better than a placebo.

The placebo effect[21] can be as much as 70-90% as effective as traditional psychiatric treatment (medicine, education, counseling) for mood disorders and about 50% effective for schizophrenia. Even deliberate use of a placebo[22] (telling a client it is a placebo) can help in anxiety and depression. And in some cases, work just as well as pharmacological treatments. Researchers say the doctor-patient relationship and expectations to recover can have very powerful effects on actual recovery.

A small analysis of 10 studies[23] concludes that psychotherapy is as effective as antidepressants in recovery from depression. A larger study analyzing many small studies[24] with a total of almost 30,000 patients suggests psychotherapy and medication are equally helpful in coping with depression and improving quality of life. But, the combination of both is better than just psychotherapy or medication.

Takeaway: Medication can be a more economical solution (by itself, with therapy, or with a placebo) because it is generally easier to take pills than work through a therapeutic process for the same outcome.

6. More money can solve problems that people try to solve with therapy

Sometimes, getting money works better than therapy or psychological interventions! In one study[25] on about 5000 low-income Kenyans, researchers compared the effect of therapy, money transfer, and a combination of both on psychological and economic health. They transferred 50,000 KES (about 20 months of consumption per capita, equivalent to 1,000 USD at that time) as a lump sum to some participants, or gave 10,000 KES over 5 weeks along with 5 corresponding therapy sessions, or delivered just 5 weeks of state-of-the-art therapy sessions as per a WHO protocol. The end result? Those who received 50,000 KES in one lump sum had better psychological well-being, economic health, and adjustment to circumstances even after a year. The money was unconditional money – the recipients were free to use it however they’d like. According to the authors, one possible reason therapy failed was that the therapy (called Problem Management Plus) was a general-purpose therapy and wasn’t tailored to specific pre-defined problems. The researchers say, in that context, a donor giving money would be more beneficial than investing in psychotherapy for others. The cost of delivering psychotherapy is far higher than transferring money with no benefit to show for the higher costs. Maybe you need more money and less therapy?

Perhaps you’d think winning such a lottery is the reason the study showed improvements in the money-transfer group. Who doesn’t like free money? However, the link between income and mental health is well established. A drop in household income and low income[26] are both large risk factors for poor mental health across the lifespan. Money can help you manage prominent stressors[27] in life that would’ve otherwise led to larger mental health problems.

Takeaway: Since money can remove stressors, make you feel in control, help you take risks and recover from them, improve quality of life through good purchases, give a sense of security, and make adjusting/adapting to new circumstances easier, financial well-being might heal psychological distress better than therapy.

Questioning the very nature of psychological research

7. Bad research leads to bad therapeutic insights

Advanced computational methods[28] used to analyze symptoms in patients over time clearly demonstrate one mental health problem transforms into another one. This makes the idea of diagnosis and fixed approaches problematic. Newer trends in understanding mental health symptoms suggest many causal factors work together in a way that starts a self-sustaining network of problems. Even when the causal factors are gone, the network continues with one symptom leading to other symptoms. So hunting for the “true cause” is not always as helpful as tackling the issues for what they are.

This is consistent with the idea that psychiatric diagnoses are themselves poorly created and don’t help to formulate a person-centric therapy plan. A robust study titled “heterogeneity in psychiatric diagnostic classification[29]” says the diagnostic criteria and disorder descriptions overlap too much for them to be meaningfully conceptualized as separate unique problems. It also says the role of trauma is poorly included in diagnoses. The paper concludes by saying that instead of relying on a bad diagnostic system of “disorders”, a person-centric approach taking individual factors is more useful. The current trend in understanding disorders is that diagnostic theory psychology and psychiatry is weak, and this includes ADHD, Depression, Personality disorders, PTSD, etc. Essentially, being diagnosed for psychological help has less value than being understood as a person.

The standard method of getting a diagnosis also becomes less useful because the diagnostic criteria themselves don’t account for change over time, and healing is, by definition, change over time. Take the classic problem of Depression. While most people have common depression elements like not feeling aroused or excited by anything, everyone’s depression is unique. It manifests differently. And most people cope with it in different ways. So they use mental health tools to suit their needs.

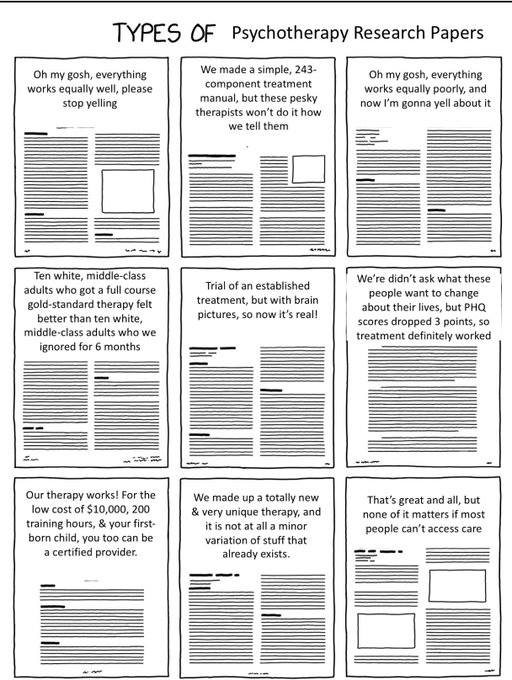

The xkcd comic below[30] summarizes the state of research quite well. An inherent lack of credibility[31] in psychological research might contribute to poorly constructed therapies that influence the usefulness of therapy in improving one’s well-being. Lack of credibility in psychological research is itself a problem in its own right that deserves more details, but here are some highlights:

- Research is not replicated making certain findings unreliable claims.[32]

- Journals (and authors) publish positive results and hide studies that show interventions had zero effect on the outcome. So it becomes harder to find out of the therapy failed, or if the research failed in capturing the effects. (more on the publication bias here[33])

- Researchers don’t retract poorly done research, and even when they do, the poorly done study is still cited. (more on the topic here[34])

- Certain types of theories and therapies (CBT, for example[35]) are more researched because they are easier to study/test, creating the illusion they are better theories/therapies. But researching others equally in-depth would perhaps create a new “gold standard.”

- Psychology has weak theories[36], and new research[37] isn’t adding much value to making a robust theory.

- Research is interpreted in very different ways by different professionals.[38]

- Popular but inaccurate ideas that gain attention warp and morph into myths, misinformation, and resistant-to-change methods used by all kinds of professionals.

Takeaway: Psychological science doesn’t have too much to say with certainty as one can in biology or physics. Research findings that seem to give you a helpful insight might not be reliable, so your mileage may vary.

If you want to take a DIY approach to mental health, I recommend starting here. If you want to seek therapy via apps, here’s my curated list of the best mental health apps and what they help with.

Sources

[2]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4159061/

[3]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4536930/

[4]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4219072/

[5]: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00347/full

[6]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307557461_Meta-analysis_of_Psychotherapy_Dropout

[7]: https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0028226

[8]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29477890/

[9]: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/tmj.2021.0294

[10]: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095424

[11]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/da.22728

[12]: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub4/full

[13]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2957279/

[14]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jsr.12568

[15]: https://jme.bmj.com/content/47/7/444.abstract

[16]: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/behavioral-and-brain-sciences/article/abs/an-analysis-of-psychotherapy-versus-placebo-studies/08C6F3704103BE1DE8737138D61BE66B

[17]: https://iaap-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/aphw.12315

[18]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7912085/

[19]: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/incps/2015/00000030/00000004/art00002

[20]: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32802-7/fulltext

[21]: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-99534-z

[22]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6003660/

[23]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23552610/

[24]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5244449/

[25]: https://haushofer.ne.su.se/publications/Haushofer_Mudida_Shapiro_Cash_Therapy_2020-11-23.pdf?fbclid=IwAR16U3l9HevjbPbEFB3QVrN3iXYsJ-_ZPEbU6VvqC5PxAcz5n58mEXDdW4E

[26]: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/211213

[27]: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2009001/article/10772/findings-resultats-eng.htm

[28]: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-14901-8

[29]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165178119309114?via%3Dihub

[30]: https://xkcd.com/2456/?fbclid=IwAR3XayGOKVaHunvlVY-P3-vWcW2TrATXVm1P7-natzuO57FlDRWJ_KU5VNc

[31]: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011845

[32]: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095710

[33]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4156299/

[34]: https://retractionwatch.com/category/psychology/

[35]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5797481/

[36]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1745691620970586

[37]: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0247986

[38]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.1.195

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.