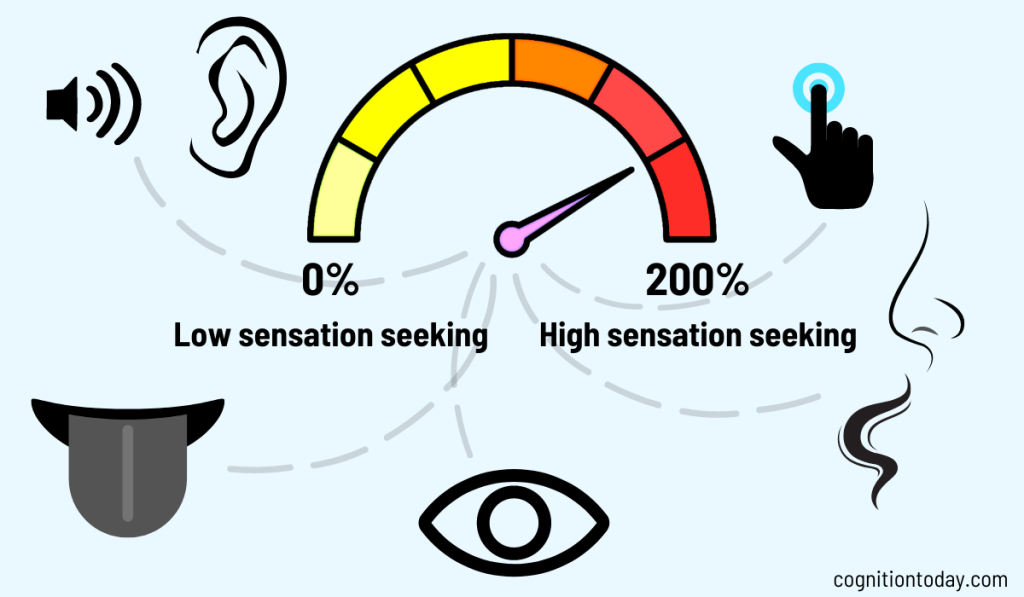

Sensation seeking is the tendency to seek high-intensity experiences and novelty. Sensation seekers typically want bold, complex, varied, and dramatic experiences as opposed to mild, simple, familiar, and calm ones. Sensation seekers might be more inclined to watch dramatic or intense TV shows, prefer adventure sports and heavier/stimulating music, and have rich tastes in food. In some cases, high sensation seeking leads to risky behavior.

Components of sensation seeking

Marvin Zuckerman, a pioneering psychologist from the 1960s, defined a core personality trait called sensation seeking as a need for “varied, novel, complex, and intense sensations and experiences, and the willingness to take physical, social, legal, and financial risks for the sake of such experiences.”

Sensation seeking (SS) isn’t 1 single personality trait. Like many other things, it is built out of more rigid components that guide behavior uniquely. It is usually measured using Zuckerman’s Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS)[1] or the newer Arnett Inventory of Sensation Seeking (AISS)[2]. Both tools take a different perspective on sensation seekers’ behavior.

The SSS tool defines 4 dimensions of sensation seeking.

- Experience-seeking: It measures the tendency to gain new experiences. These may range from going to new restaurants to valuing rich experiences with people.

- Thrill and adventure-seeking: It measures the tendency to participate in thrilling and exploratory activities. These may range from doing adventure sports to taking risks.

- Disinhibition: It measures the tendency to show little restraint or self-control and act impulsively without thinking much about consequences. Being disinhibited would mean one easily takes risks, is prone to addictions, speaks freely, acts boldly, shows strong emotions like aggression, seeks instant gratification, breaks the rules, or misbehaves. Disinhibition also explains how many of us behave on the internet.

- Susceptibility to boredom: It measures how easily one gets bored and needs something to counteract the boredom. Being high on this dimension would mean one tries hard to avoid boredom, routines, and mundane activities or reacts strongly when boredom sets in. This dimension is typically more prominent in males.

The AISS tool takes a more simplified approach. It defines only 2 aspects of sensation seeking.

- Novelty: The tendency, motivation, and propensity to seek and get excited by new experiences, objects, etc. For example, a sensation seeker with a very high preference for novelty would want to buy the most unique, new, or high-tech gadgets rather than those that just do the job.

- Intensity: The tendency, motivation, and propensity to value and seek high-intensity stimuli. For example, while browsing Netflix, high-intensity would mean preferring more violent or larger-than-life movies over the more slice-of-life or PG13 movies.

Having most or all of these dimensions as highly influencing factors that guide your behavior and thoughts would make you a high sensation seeker. Otherwise, a low sensation seeker.

High vs. Low sensation seekers

Personal preferences arise from many complex factors such as personality, past experiences, circumstances, availability, affordability, etc., but sensation seekers have preferences[3] based on novelty, stimulation, and excitability.

| Behavioral choices | High SS | Low SS |

| Movies | Dramatic, over-the-top, violent, R-rated | Mild, realistic, simple themes |

| Food | Complex tastes, spicy, extra *insert flavor, | Simple |

| Vacations | Adventure, grand natural features, high luxury | Relaxing, quiet |

| Purchases | Choosy, Novel and Unique items | Not very choosy, functional and moderate |

| Sex | High exploration, large appetite, extreme fetishes | Easier to feel satisfied, vanilla |

| Music | Loud, complex, rock, metal/synthwave-like, dramatic | Light and non-aggressive music |

| Environment | Noisy, urban, active | Peaceful, laid-back |

| Sports | Thrilling and high intensity | Safer and less aggressive |

| Risks | Take chances, wishful thinking, downplay -ve consequences, impulsive | Rely on certainty, avoid risks, well-prepared |

| Visual elements | Loud, blingy, colorful, reds, gold | Minimalistic, pastel, blues, cold soft tones |

Emotional makeup of high and low sensation seekers

Low sensation seekers (low SSers) perceive emotions with low intensity[4] better and are highly responsive to negative emotions, which gives them better risk-avoidance tendencies. High sensation seekers (high SSers), on the other hand, are less responsive to weak emotions and prefer stimuli that create strong emotions, even if they are negative emotions.

High SSers are also easily bored with mundane things and find it hard to control their urges. Low SSers can handle boredom better and exert more control over their urges. However, stress can demotivate low SSers while some high SSers thrive in stressful scenarios. Because of high disinhibition in high SSers, they may find it harder to control their emotions than low SSers.

High SSers are also likely to be more aggressive. Why this happens is unclear.[5] Aggression may be an outcome of seeking intense stimuli that generate anger/aggression, or aggression may be the method to seek more arousal. For example, you may seek out movies that make you angry because you like the intensity, or you may aggressively hunt for a particular item to feel a sense of reward.

Sensation seeking can be a risk factor[6] for psychological disorders with a strong emotional component like manic-depressive episodes, drug addictions, and psychopathy (lacking empathy and emotionally insensitive). One contributing factor for these disorders is that sensation seeking can lead to risky behaviors, undervaluing negative consequences, and weak reactions to average-intensity situations.

High Sensation seeking is a tendency to

- Show blunted anxiety and low avoidance of intense stimuli: You are less likely to feel the threat and danger that motivates you to avoid something.

- Show high appetitive & approach motivation: You want to go closer to something or consume something for a potential reward.

Low Sensation seeking is a tendency to

- Show heightened anxiety and high avoidance of negative stimuli: You are more likely to feel the threat and therefore avoid risks.

- Show low appetitive & approach motivation: You are more likely to seek safety and comfort as opposed to novel stimulation.

Appetitive motivation refers to the desire to consume something rewarding. For example, ordering a tasty meal. Approach motivation refers to the desire to go closer to a stimulus. For example, going closer to touch a slimy object.

Sensation seeking across gender and age

Males are typically more sensation seeking than females in the US, Europe, Canada, and Australia. However, in a study on Australian people[7], women between 30-39 had a higher sensation seeking score. While experience-seeking decreases for males over their lifespan, it appears to increase for females until 40 years of age and then decline to comparable levels in males.

There are cultural differences that affect men and women differently in expressing sensation seeking behaviors. In a study on Chinese people[8], men had higher sensation seeking scores overall, and sensation seeking did reduce with age. Still, the intensity of sensation seeking was lesser than that observed in western countries. 30-39-year-old-men had more disinhibition (rebellion, inappropriate behavior, physical risks, low obedience, etc.) than other age groups, which may be a direct consequence of social and cultural principles. Women also had lower disinhibition and thrill/adventure-seeking tendencies than men.

Adults across most cultures are typically less sensation seeking than adolescents. As people grow older, sensation seeking behaviors tend to reduce. This is also closely related to how a general risk-taking tendency reduces with age. A study suggests[9] that 16-18-year-olds with high sensation seeking tendencies are also likely to be more aggressive than their low sensation seeking peers making them particularly prone to severe negative consequences, addictions, and crime.

There are subtle differences in how men and women exhibit their sensation seeking behavior. For example, between high sensation seeking males and females, males are more likely to get bored[10], and females are more likely to not monitor[11] their own behavior.

Sensation seeking and risk-taking

Sensation seeking may contribute to risk-taking behaviors through multiple mechanisms. Common mechanisms include:

- Undervaluing negative consequences

- Undervaluing gains and losses alike

- Perceiving a higher thrill in risks

- Inability to process problems/risks while they occur

Teenagers with high sensation seeking may be prone to trying out new drugs. In one study[12], low sensation seeking was related to having more negative views toward drugs, and high sensation seeking was related to a positive attitude and intention to try some drugs like marijuana.

Sensation seeking contributes to risky driving for young people[13]. The “reward of taking risks” might affect young male drivers more. For example, taking and surviving a risky road thrill may give a favorable social status to young males motivating them to take risks if they overvalue that reward and undervalue the risk.

Undervaluing negative consequences or insensitivity to errors is a core theme in sensation seeking behavior. One study found[14] that females have blunted error-related negativity while performing a task that needed them to stop or continue a response based on an instruction. Their low error-related negativity suggests their brains undervalued the errors and continued performing. Error-related negativity occurs when we spot errors while monitoring our performance. Another study[15] shows that sensation seeking tendencies are more related to differences in monitoring performance and not actually stopping a response. This means a high SSer might continue doing something wrong or risky without realizing it is a problem until they realize it and then stop appropriately.

In a study looking at SSer’s gambling behavior, researchers observed that high SSers had weaker neural responses to both gains and losses while anticipating and evaluating them. According to their data, low SSers had risk-avoidance tendencies, and high SSers had a weaker perception of the risk itself. Since high SSers underestimate the gain/loss compared to low SSers, high SSers need excess gains/losses to match the magnitude of gains/losses estimated by low SSers. For example, a high SSer might need 4 drinks to feel as satisfied as a low SSer who had 2 drinks. Or they may need a more intense horror movie to feel as scared as a low SSer watching a low-intensity horror movie.

Biology of sensation seeking

The orienting reflex[16] is strong in high sensation seekers. The orienting reflex is the body’s way of aligning its senses and attention to changes and new stimuli in the environment, so the body is more sensitive and attentive to that stimuli. If the change is sudden, any person may get startled. But if the change is small, a high sensation seeker will orient toward that novel stimuli (the change in the environment) faster. This makes sensation seekers better at spotting new stimuli like rare birds, insects, or strange things around them. Typically, low sensation seekers have a weaker cortical response (brain activity to process new things) but a high heart rate after exposure to novel/thrilling stimuli. Researchers believe this may be because low sensation seekers are more defensive (and safety-oriented) in novel situations.

Anxious states[17] may counteract a high SSer’s ability to orient to novel stimuli. So a high SSer experiencing high anxiety may not exhibit sensation seeking tendencies.

One theory[18] explaining sensation seeking behavior is that the nervous system of high SSers is more excitable than that of low SSers. That, in turn, gives them a strong central nervous system response[19] to novelty, meaning they are more excited at a biological level with odd things around them. Their brain and the nervous system are sensitive to and hyper-aroused by novel stimuli. However, like low sensation seekers, they get used to (or habituated to) new things just as easily. This explains why they can get bored with new things too.

How does sensation seeking start?

A study tested 3 theories of sensation seeking[20] on 10-month-old infants by showing them a video 10 times.

- Optimal arousal theory: This theory suggests high SSers crave more stimulation when their nervous system is not sufficiently aroused by current sensory stimulation. It suggests that high SSers have low default arousal, which they try to increase via high stimulation. And conversely, low SSers have high default arousal, which they try to dampen or decrease via low stimulation. This was also Zuckerman’s original explanation.

- Information prioritization theory: This theory suggests SSers have a bias toward incoming information than ongoing processing in the brain. As a result, they prefer novelty in the environment over their current or previous mental state.

- Processing speed theory: This theory suggests that those who have higher processing speed (a component of intelligence) tend to seek more intense stimulation that matches their capacity to process it. So, they would seek novelty and complexity and make use of their higher processing speed which generates sensation seeking tendencies.

The study on 10-month-old infants supports the Information prioritization theory.

Note: High excitability of the nervous system is not the same as having high default arousal. Any baseline arousal can be more (or less) sensitive (excitable) to stimulation.

The optimal arousal theory, which is perhaps the more intuitive one, has weak support. For example, one study[21] failed to provide evidence for changes in behavior due to changes in central nervous system arousal. They tested whether high SSers perform better than low SSers when their less aroused nervous system is more aroused via medication. Similarly, they also tested whether low SSers perform better than high SSers when their more aroused nervous system is dampened via medication. The nervous system depressant or stimulant did not affect SSers behavior enough.

It is possible that the elements of all theories work together.

Modifying sensation seeking behavior

If High or Low sensation seeking is preventing you from leading a life you’d like, here’s something to think about.

If you are a high sensation seeker, try to analyze the risk you are taking for a thrill. The excitement can cost you more than you anticipated. Start with seeking 90% of what you crave and lower it down to 50% till you appreciate new sensations. Deliberately pay attention to details that may spark excitement in small doses.

If you are a low sensation seeker, have a healthy balance of safety and risk. Risks can bring good rewards. Start with increasing the intensity of your experiences by 10% and stop when you are satisfied. The excitement that comes from novelty and new experiences might help you develop a strong component of happiness and life satisfaction called “psychological richness.”

Sources

[2]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0191886994901651

[3]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-13895-004

[4]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301051111001505

[5]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ab.20369

[6]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1980-28099-001

[7]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-09529-001

[8]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886999000926

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0191886994901651

[10]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1971-09995-001

[11]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/psyp.12240

[12]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886901000320

[13]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0001457512002126

[14]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/psyp.12240

[15]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/psyp.13373

[16]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00918.x

[17]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1976.tb00098.x

[18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0191886989902262

[19]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1976.tb00098.x

[20]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32748567/

[21]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7077524/

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.