Over 72% people are exposed to misinformation at least once a month on social media, according to this detailed list of statistics[1]. If you think about it, this number itself is quite modest – 7 out of 10 people see misinformation at least once in 30 days? I’d have estimated about 5 times per day for everyone who is on social media daily.

But the bigger problem is not even knowing you’ve been exposed to misinformation. This, of course, happens in your WhatsApp university, comment sections, and while doom-scrolling news events that are translated, summarized, and attention-grabbingly repeated with minor errors by 100s of content creators that eventually enter public awareness with those minor errors compounded into full-blown false claims.

Only 42% of the online world[2] trusts information on social media, and surprisingly, a fairly large number (48%)[3] of 12-15-year-olds in a UK sample already know that they could do a quick fact check by looking at comments and validate information by comparing it with other sources.

Only if countering misinformation were that simple. Unfortunately, too many psychological factors contribute to believing misinformation. These simple validation tactics, like cross-referencing and verifying through comments, often fail, even though, quite often, there is a commentor saying, “Chat, is this real?” or “Where is the paragraph guy?” Fortunately, there are enough experts around who want to share their expertise and validate information and clear the confusion in comments, and in a smaller group of responsible content creators, these comments get pinned.

I’ll outline these psychological variables below.

Illusory truth Effect

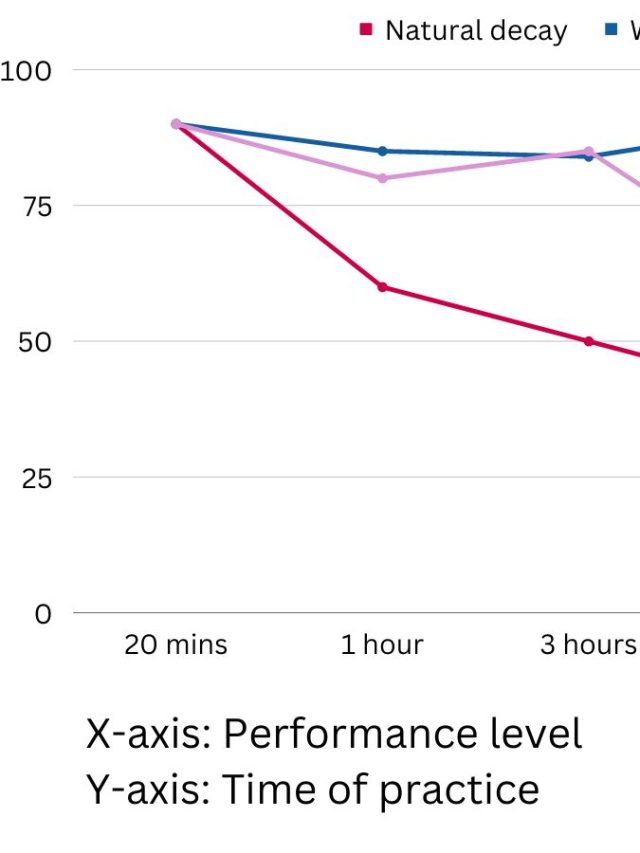

When misinformation is repeated for a long time or many times, it gets easier to process. That ease of processing tricks the brain into thinking it is familiar and correct.

Tip: Just because it is easy to process and familiar, doesn’t mean it is accurate.

Psychological comfort

Misinformation, typically found in pseudoscience and spiritual areas, tends to comfort people with hope when dealing with extreme uncertainty and ambiguity.

Tip: Emotional judgments of feeling hope aren’t a validation metric

Not psychologically inoculated

People tend to remember what they learn first. If they don’t learn the facts first, they don’t get inoculated against future misinformation. Basic facts work like a vaccine for misinformation[4].

Tip: Learn things, a lot of things

Confirmation bias

With enough versions of facts and narratives available, people tend to choose only the ones that support their beliefs. They ignore the rest.

Tip: Derive what you can from this article because it is my personal analysis, and not the outcome of a study. Question what I’ve said here too.

Lack of context

Some facts and scientific ideas are difficult to grasp without foundational knowledge and context. In such cases, it is easy to reject the facts in favor of a simpler idea, even though it is wrong.

Tip: Listen to someone who knows better instead of doing your own research in areas you haven’t studied critically.

It’s a better story

Stories persuade people better than facts. If misinformation tells a more compelling story than science does, misinformation wins.

Tip: Science fiction and Fantasy can give the same satisfaction as a good story

Hypo-cognition

To understand complex phenomena, we need the appropriate vocabulary and mental tools to understand it. These tools can be math, language, metaphors, diagrams, etc. Without those, people are in hypo-cognition (lacking mental tools), so they absorb misinformation that fits their tools.

Tip: Learn technical words and concepts so you know how things work

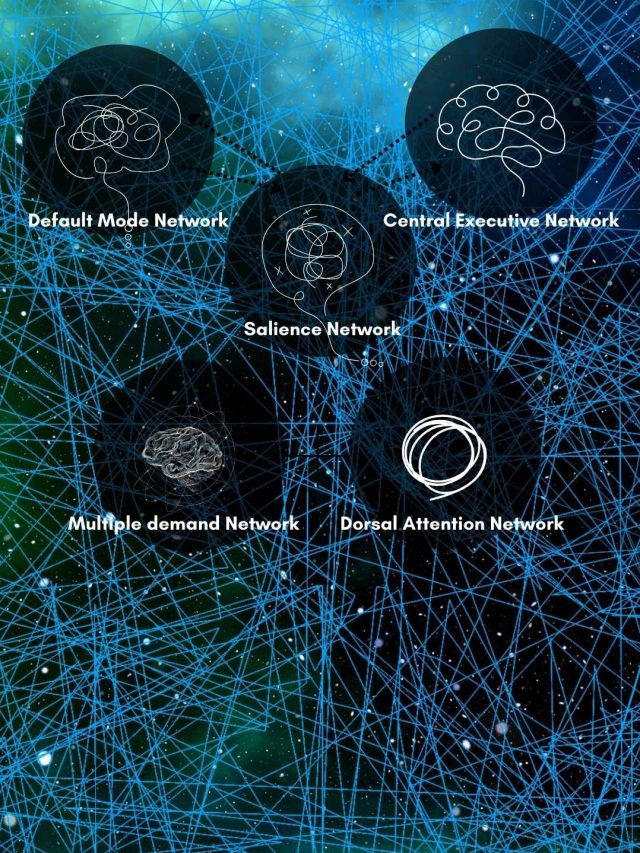

System 1 thinking

System 1 thinking is based on feelings and quick judgments. System 2 is the opposite—slow and effortful. Misinformation quickly latches onto system 1 thinking, especially when we are busy and stressed.

Tip: Slow down and think

False Face validity

Some misinformation appears correct[5] because it has all the right words, feels trustworthy, is endorsed by people with expertise, etc. It contains linguistic trust signals that manipulate communication to persuade others to believe what an author is saying. Illusory pseudoscience depends on this, too – they have technical words, experts who “study” it, historical records, etc. It feels scientific, even though evidence is never presented. So if misinformation is padded with details like “Dr. Jones said…, scientists have found…, published in XYZ journal,” we think it is credible. The actual information in it is rarely verified. This problem is compounded by the fact that most people aren’t experts at most things, and they fundamentally lack the knowledge and contextual understanding to even interpret data and concepts.

Tip: Look for evidence and analysis when a non-expert is trying to make a strong appeal to some authority saying something

Gell-Mann amnesia effect

We routinely dismiss other people’s analyses on topics we are experts in, but if the same people give an equally in-depth analysis of a topic we aren’t experts in, we tend to accept it, even with the author’s flawed logic. We often forget that we had dismissed their logic in one area, yet accepted it in another. In familiar topics that get analyzed, we spot their mistakes, but in unfamiliar topics, we don’t.

TIP: Judge if a person’s analysis is the problem or if the original information source is a problem. E.g, are they unknowingly repeating misinformation, or are they confidently making misinformed claims?

The need to make sense

We have a need to make sense of the world, even if it doesn’t fit science. If misinformation makes sense of our circumstances, we tend to commit to that misinformation to clarify the world. Political conspiracy or narrative building often achieves sense-making in a demographic.

Tip: There’s nothing we can do; humans love fantasy and interpret things that give them comfort.

The unfortunate outcome of DoInG YoUr OwN rEsEaRcH

Look at these psychological variables.

If it appears often on social media, it feels true (illusory truth effect). If it matches something similar to what you’ve heard, it feels true (confirmation bias). If it has references to scientists, it feels true (false face validity), if it is outside your area of expertise, you’ld believe it (Gell-Mann amnesia effect). If it doesn’t explain your personal/emotional experience, the science must be wrong (the need to make sense).

All of these problems effectively interfere with your ability to do your own research and arrive at an accurate conclusion. So, as a bonus variable, I have to conclude that doing your research may just create another variation of misinformation – the one you create in your head.

Also, considering these, there are a few ways to counter misinformation, but they aren’t easy to form habits, and they are likely to fail because of our system 1 thinking – the fast, speedy thinking process that quickly passes judgment and moves on to the next task.

- Be open to trusting an expert who can cleanly explain their thought process.

- Reject a person whose biggest source is “trust me bro”.

- Learn early and learn a lot so your basic knowledge inoculates you from believing and propagating dumb, deluded disinformation.

- Learn to understand confusion so you can recognize where others may be confused with what you say.

- Instead of ambiguously getting a “feel” for things, learn some technical terminology and technical processes so you have the mental tools to parse new information.

You probably know this – defending against misinformation is hard and requires a lot of mental effort. Not everyone is up for it most of the time. The least that most people can do is accept that they have fallen for misinformation and are open to changing their thought process.

And that is a different ugly mess, which I wrote about a few years ago.

Sources

[2]: https://www.statista.com/statistics/381455/most-trusted-sources-of-news-and-info-worldwide/

[3]: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1268663/children-factchecking-online-news-united-kingdom-uk/

[4]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10463283.2021.1876983

[5]: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.646820/full

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.