Despite the commonly known positives of high intelligence, there are a few negative cliches like super-intelligent people are prone to mental disorders, are impulsive, have anxiety-induced mental performance issues, or are romantically less desirable. Regardless of being stereotypes, all of those cliches are at least partly supported by evidence and have coherent explanations.

It’s not that average or low-IQ people don’t have these problems; they do. Still, high intelligence sometimes contributes to and amplifies these problems.

1. Proneness to mental illnesses

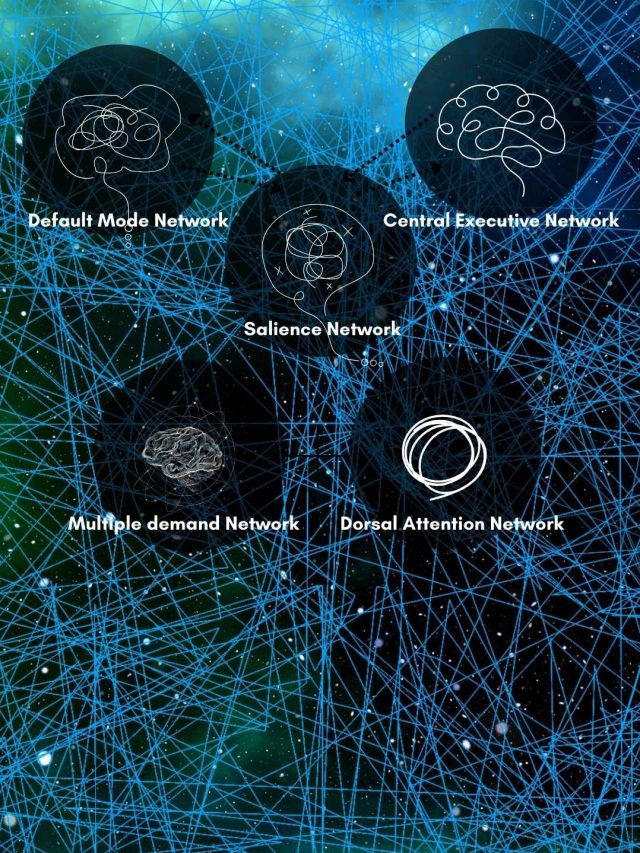

A lesser-known theory in psychology is the hyper-brain/hyper-body theory[1], which suggests that those who have a high IQ (hyper mind) are also at a higher risk of physical and mental illnesses (hyper body). Research does show that high IQ (Mensa members) have an added risk of developing mood disorders like bipolar, anxiety, and depression, ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), Autism spectrum disorder, and immunity problems like allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases. One reason this could happen is that those with high IQ might overthink, worry a lot, or overreact to environmental stress, leading to an over-dramatic response from the immune system, akin to a hyper body, which we know is a state of physiological excitability (stress hormones, cytokines). So, a high-IQ brain could be hypersensitive to the environment as well as internal bodily changes, which only magnifies worry and anxiety.

Micro-issues that come up: Anxiety flare-ups, allergies, depression via lack of social connection, depression via overthinking

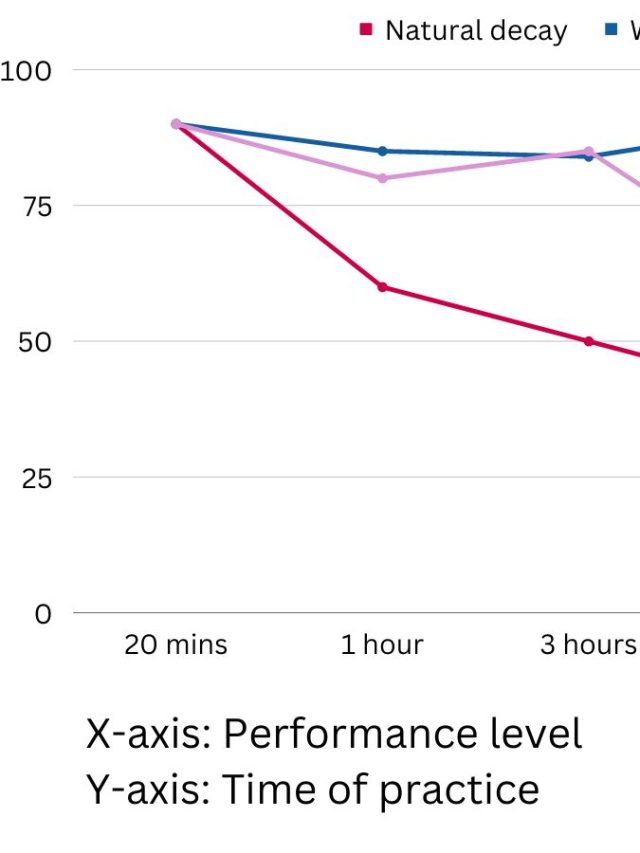

2. Anxiety-induced performance issues

A large component of intelligence is working memory. It is our ability to hold and manipulate information in the mind for a short duration. Our current thoughts, self-talk, factual data, and neutral information like login OTPs, etc., rest in our working memory. Research shows that people with high working memory[2] can have a lot of anxious thoughts while performing tasks when the stakes are high, such as critical job applications, stage performances, or big-money deals, confessions of love, or final exams. So when the consequences of performing have a lot of value, it tends to choke up working memory with negative thoughts. Working memory helps us perform well; when it is choked up, our performance drops because there is less space in the mind to have constructive thoughts.

Micro-issues that come up: avoidance of difficult tasks, difficulty accepting failure

3. Difficulty having romantic success

People love to say they want an intelligent partner, but surveys show a limit to how intelligent.[3] Up to the 90th percentile in intelligence (120 IQ), people find intelligence desirable. But for higher intelligence (top 10%), they begin to show concerns about social skills and compatibility. This doesn’t necessarily mean that intelligent people are bad at socializing; it just shows people have these concerns before making dating decisions. There seems to be no such limit for emotional intelligence. People straight-up find emotional intelligence desirable up to the 99th percentile. They also find emotional intelligence slightly more attractive than cognitive intelligence. A combination of high emotional intelligence and not extremely high intelligence would be quite attractive, if we were to generalize the research.

Micro-issues that come up: Self-isolation, lack of effort to seek a partner, rationalizing why a partner is not needed

Read more about the psychology of love and romance here.

4. Difficulty controlling impulses

For adults[4], high intelligence is associated with 2 important aspects of impulsivity – low scores on delay discounting and high scores on non-planning (improvising, winging it, going unprepared to shop, etc.). Low scores on delay discounting mean it is more difficult to avoid instant gratification, or there is a preference for immediate rewards or devaluation of future rewards. Intelligent people might rely on their intelligence to afford the risk of not preparing enough or “repairing” the negative consequences of impulsive actions. It could also be a form of sense-making with the belief that intelligence can somehow compensate for impulsivity-related drawbacks. This problem is also associated with a related type of personality called sensation-seeking, in which people seek out over-stimulation and show risky behavior. One key mechanism with intelligence is that over-stimulation offers more potential to engage with.

Micro-issues that come up: Ignoring safety guidelines, regret about impulsive decisions

5. Childhood loneliness

While there is no consensus that intelligence causes loneliness, there is experimental evidence[5] that very intelligent people (IQ above 130) tend to be lonelier than people with average IQ (around 100) while growing up. However, the study also found that loneliness tends to reduce as they grow up and adjust to life. This childhood and adolescent loneliness is linked to 2 primary factors: One, feeling different and not relating to others. Two, choosing activities that stimulate the mind (games, puzzles, etc.) instead of choosing those that stimulate relationships (sports, talking, etc.)

Micro-issues that come up: Less familiarity with social cues and body language, difficulty trusting, rejecting companionship

Using these specific mechanisms, there are ways to cope with the downsides.

Coping with the downsides of intelligence

I’ll suggest some specific tips as a vanguard against the problems faced by highly intelligent children, as well as highly intelligent adults.

Prone to mental illness

Children

- Encourage balance between intellectual stimulation and physical activity (sports, play, outdoor time).

- Teach emotional regulation skills early (mindfulness games, journaling, naming emotions).

- Provide safe outlets for overthinking (structured hobbies like music, drawing, or puzzles).

- Foster friendship instead of competition between parents (and by extension their children) of other intelligent children.

Adults

- Practice stress-regulation techniques, meditation, exercise, journaling, or any other stimulating hobby.

- Avoid taking on the burden of solving every problem yourself.

- Balance high cognitive work with body-calming routines (yoga, regular exercise, sleep hygiene).

- Avoid intellectualizing every personal-life problem.

Anxiety-induced performance issues

Children

- Train test-taking strategies (practice under mild stress, progressive exposure).

- Reduce performance pressure at a system level by creating an environment where failure is a valid outcome of performance.

- Increase parental acceptance of changes in performance without judging the child for being weak or incompetent.

- Increase reliance on habits that are created specifically to deal with performance.

Adults

- Use cognitive offloading (lists, reminders) to free up working memory.

- Ask for help.

- Practice performance routines (breathing, pre-task rituals) to reduce anxiety choke.

- Rehearse under simulated pressure to inoculate against stress.

- Reframe high-stakes performance as a challenge, not a threat.

- Increase reliance on habits that are created specifically to deal with performance (autopilot can save adults when emotions are out of whack or the mind is clouded)

Difficulty having romantic success

Children

Out of scope for this context

Adults

- Dissociate the idea that a partner is an intellectual achievement

- Practice vulnerability and openness in relationships instead of relying only on intellect.

- Join groups where similarly intelligent people (in case of wanting intelligent partners) or interact with a variety of people (in case of wanting a partner in a different domain) in non-intellectual pursuits like nature-based hobbies.

- Re-allocate focus to aspects of others’ behavior that aren’t directly tied to achievement.

Difficulty controlling impulses

Children

- Teach self-monitoring skills (pause before acting, count to five).

- Use reward systems that emphasize delayed gratification.

- Provide structured environments that channel impulsivity into creativity (arts, coding, sports).

Adults

- Practice delay of gratification (e.g., 24-hour rule for purchases, no-expense days, or no purchase above pre-set budget, etc.).

- Understand the hot-cold empathy gap to locate the “source” of impulses.

- Use commitment devices (pre-commit to savings, accountability partners).

- Channel sensation-seeking into safe stimulation (adventure sports, challenging projects).

Childhood loneliness

Children

- Encourage both mind-stimulating and relationship-stimulating activities (board games, collaborative homework).

- Normalize feelings of being “different” while highlighting shared experiences with peers.

- Introduce mentors or slightly older peers with similar abilities for role modeling.

Adults

- Reconnect with like-minded communities (clubs, intellectual meetups, online groups).

- Invest in relationships where differences are celebrated rather than alienating.

- Practice balancing solitary intellectual pursuits with shared experiences.

- Recognize that loneliness often decreases with maturity — patience and effort matter.

Sources

[2]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03213916

[3]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016028962030043X

[4]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019188690600256X

[5]: https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/28009

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.