Highlights

Curiosity & Confusion are 2 of the most powerful emotions in education.

🤔Curiosity leads to exploration and filling one’s knowledge gap.

😕Confusion leads to deep learning when contradictory opinions & facts resolve into a state of clarity.

Both these emotions are a different layer of emotions called “epistemic emotions,” which are emotions that make a person create knowledge. They are quite different from our usual joy, fear, happiness, and sadness type of emotions. Education needs to bring epistemic emotions to the forefront and not just cater to the basic ones.

🧠 The great thing is both these emotions can easily emerge in a highly unstructured information exchange and free-flowing experience.

When you learn something, anything, in school, or at work, we do things that are rewarded and we don’t do things that are punished. This is the basic principle of learning a behavior that guides everything alive and also AI.

But simply getting a reward for doing something correctly and getting punished for doing something wrongly is not sufficient to actually educate a person.

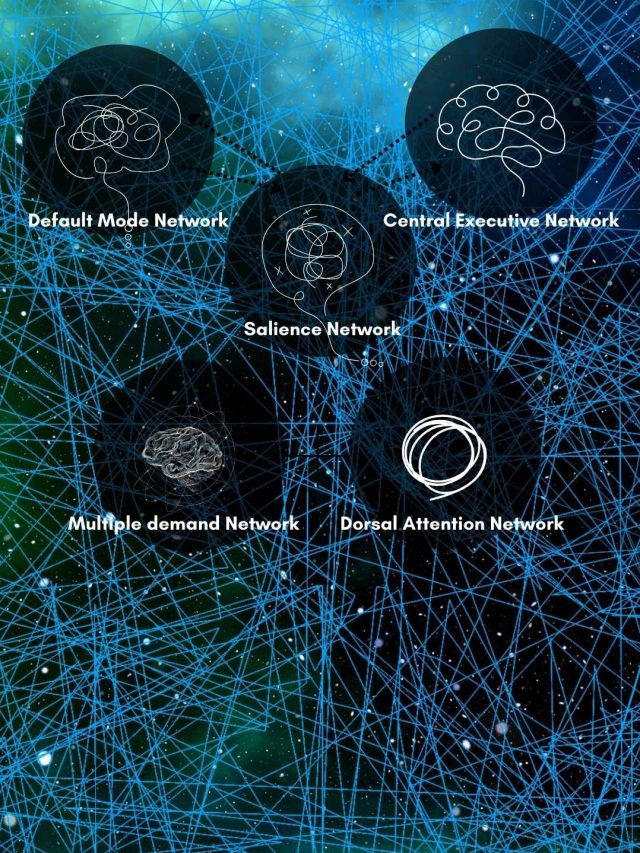

When it comes to knowledge, second-order emotions matter. These are called “epistemic feelings”.

The 2 kinds of feelings

Feeling feelings (basic emotions)

First-order emotions like sadness, joy, and fear alter our behavior automatically. Fear indicates avoidance, sadness indicates accepting a loss and lowering the body’s energy expenditure, joy indicates a reward, and disgust indicates a threat to life by disease. These are the basic emotions we are used to talking about.

Thinking feelings (epistemic emotions)

Second-order emotions like curiosity, surprise, agency, familiarity, beliefs, confusion, and doubt – alter our behavior with a deliberate effort to create knowledge. They are called epistemic feelings. So, beliefs let you understand the world. Curiosity lets you explore the world. Confusion and doubt let you gain clarity. Familiarity gives the confidence to interact. Agency lets you modify the world with your decisions, etc. All of these epistemic feelings are about knowledge. Epistemic means “related to knowledge.“ These emotions are complex and have a lot of thought related to the emotions.

Let’s look at 2 of these epistemic emotions: Curiosity & Confusion. Both these emotions are about having too little information[1], which becomes the motivation to seek more information. This means – epistemic emotions meet one of the primary goals of education – learning new things.

Education needs to focus on "epistemic emotions" like Confusion & Curiosity – the emotions that make us seek & create knowledge. Not just the basic emotions like fun, joy, and fear. Share on XCuriosity

Simply put, curiosity is any behavior that seeks to know more. We do this by peaking over a wall that blocks our vision. Animals do this by taking high-ground and looking around. Children do this by throwing things, breaking things, eating things, asking questions relentlessly. The most visible form of curiosity is asking questions and open-mindedly learning something more about a topic. Google searches, asking friends, reading books, etc.

Sometimes we are curious with a goal. Sometimes we are curiously just exploring, not knowing what we will find out. Like wandering off during a trek.

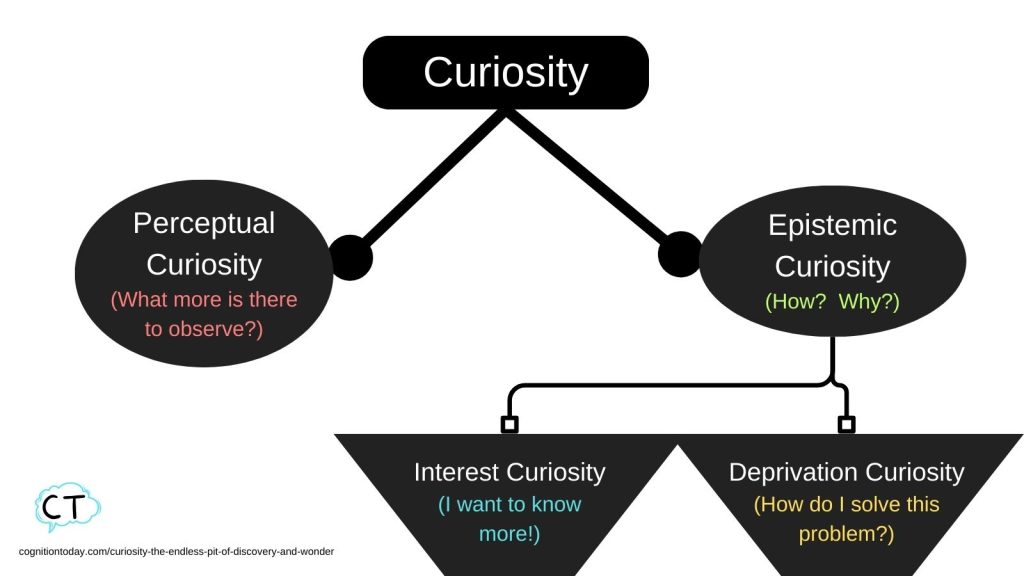

The 2 basic forms of curiosity[2] are epistemic curiosity (that we see in humans) and perceptual curiosity (that we see in animals). Perceptual curiosity is also there in humans, but we do a lot more than just try to find out more by looking around.

Imagine you are a cat. You are looking from a hidden vantage point on top of a low-rise water tank to figure out your environment full of houses, fences, and odd staircases. Meeeooooww. That is perceptual curiosity. You are simulating the environment in your brain. You are making judgments about how you would move through it. Perceptual curiosity is the intent to seek new knowledge by perceiving the world. Transform back into a human now. Epistemic curiosity now looks at how the environment was built and what different things can happen in it. Is there a hidden area that I can’t see? What can I expect there?

The epistemic curiosity we see is, again, of 2 types.

Interest-focused curiosity and a deprivation-focused curiosity.[3] Interest-focused curiosity is a path toward new knowledge because there is more to know, more to find out, and more to play with. Deprivation-focused curiosity is finding out more to solve a problem. That is the curiosity to find creative solutions and improve something.

- Interest curiosity is to discover and explore, regardless of an opportunity to explore. So if there is none, people are curious to find out how they can know more. If there is an opportunity, people will take it right away. People explore art out of interest curiosity. They try new foods out of interest curiosity.

- Deprivation curiosity is the real hard-hitting deal that governs most businesses and lives. Everyone has problems of some kind that need solving. Some people don’t solve them, and others try to solve everyone else’s problems. People invented the fork out of deprivation curiosity. Companies made mobile-first content out of deprivation curiosity because mobile behavior was not aligned with desktop behavior. Airconditioning technology comes from deprivation curiosity.

All of these different aspects of being curious make a learner learn more. It’s not just about asking more questions, its about asking more questions AND observing more things. It’s about thinking about what you learn.

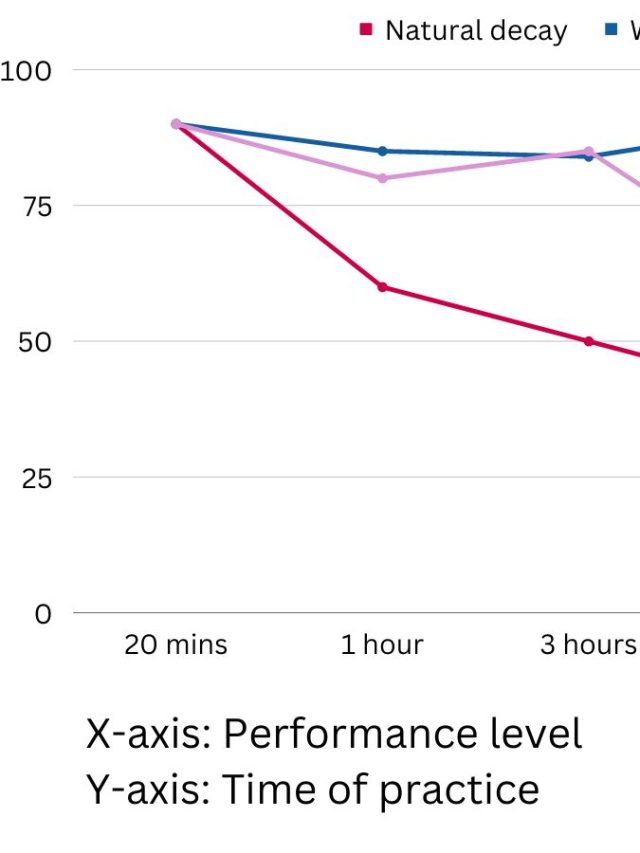

Curiosity peaks when there is small gap between what you know and what you don’t know. Let’s call it the “sense-making gap”.

Sense-making – trying to explain to ourselves how things happen, why they happen, etc. – ties 3 independent mental states together[4] – curiosity, boredom, and flow.

When there is a small gap between what you know and what you think you can find out, we get quickly curious. E.g., you learn how to cook fried rice, and then you get curious about other rice preparations.

When there is a huge gap between what we know and what we are learning, we get bored. E.g., you just learned that there are different planets in our solar system, but you are now asked to study complex gravitational equations that look like 2 cats just fought a war on your keyboard.

When there is a very small gap, but we are feeling challenged and love what we are learning, we get into the flow state. E.g., you’ve just learned how to make sentences in the subject-object-verb format in a new language, and you are doing a practice session with all the new verbs you’ve learned and go in the zone where you feel you’ve mastered it.

These 3 states (curiosity, boredom, flow) matter in the classroom. The students’ feelings are going to depend on the gap in knowledge and what they think they can understand right away. In common terms, the difficulty has to be adjusted for a majority of the students to feel curiosity. The best way to achieve this is to have a lot of variety in what students learn. This gives curiosity anchors to students where they may feel perceptual curiosity or epistemic curiosity.

Now, let’s get to confusion. The beautiful misunderstood emotion.

Confusion

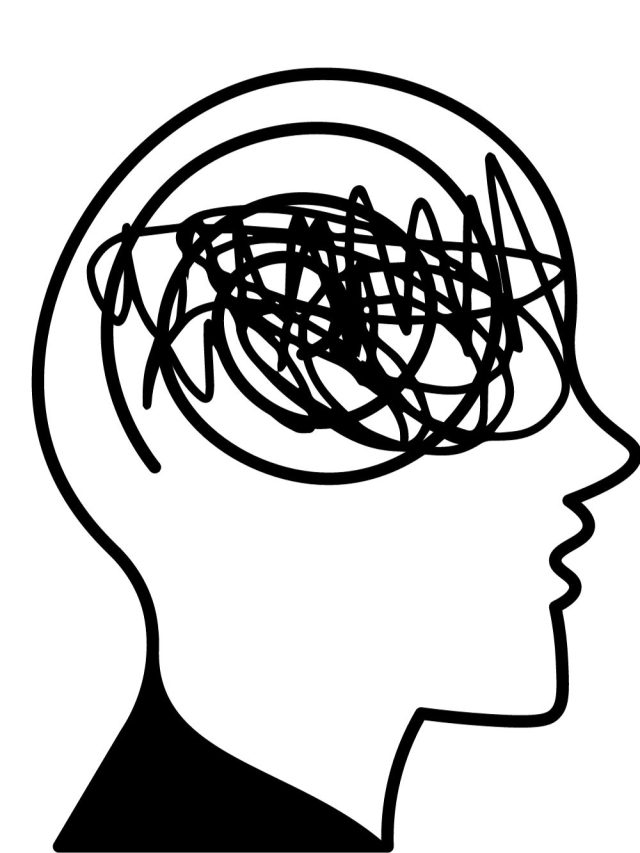

When we look at a confused students, there are 2 common interpretations. The student hasn’t learned. Or the teacher hasn’t taught well.

But, there is a 3rd perspective that matters and it shows why confusion is needed.

Research shows[5] that confusion can enhance learning when confusion emerges from contradictory interpretations of facts. The confusion gets resolved, eventually, and that leads to deep learning. The researchers found that confused learners are better at applying their learning to new situations. This confusion increases the amount of attention paid to that information.

Let’s look at a school-level example. In a biology class, students learn about a cell’s structure. “Cells have mitochondria, nucleus, golgi apparatus, etc.”

The next day, students learn about atoms. “They have protons, neutrons, and electrons.”

In a week, they have to study for a test. A practice question they get for homework is – “Where does nuclear energy come from?” Now, the student is confused and thinks – “a cell has a nucleus, but atoms have neutrons. Where does it come from???? Nucleus or neutrons?”

This form of confusion is incredibly powerful in understanding a large number of concepts. When this confusion is resolved, a student has a better understanding of 2 different fundamental structures that make up the things around us.

This perspective on confusions says that students who try to resolve their confusion do more cognitive work to reduce their confusion. That extra cognitive work contains analysis, memorizing, comparing & contrasting, asking follow up questions, etc. This confusion also induces curiosity then.

Researchers have studied confusion[6] in learning quite a lot. I’ll summarize what they know – confusion indicates there is something missing or wrong with one’s knowledge. Confusion then helps students learn when they try to resolve that confusion. The effortful cognitive activity that happens while trying to gain clarity is the active ingredient that helps learning. If confusion cannot be meaningfully clarified, it doesn’t help learning. Not all students benefit from confusion. The gap between what they know and what they don’t know affects if confusion helps or hurts. This gap can be managed by educators by having the right scaffolds (helpful hints and hand-holding).

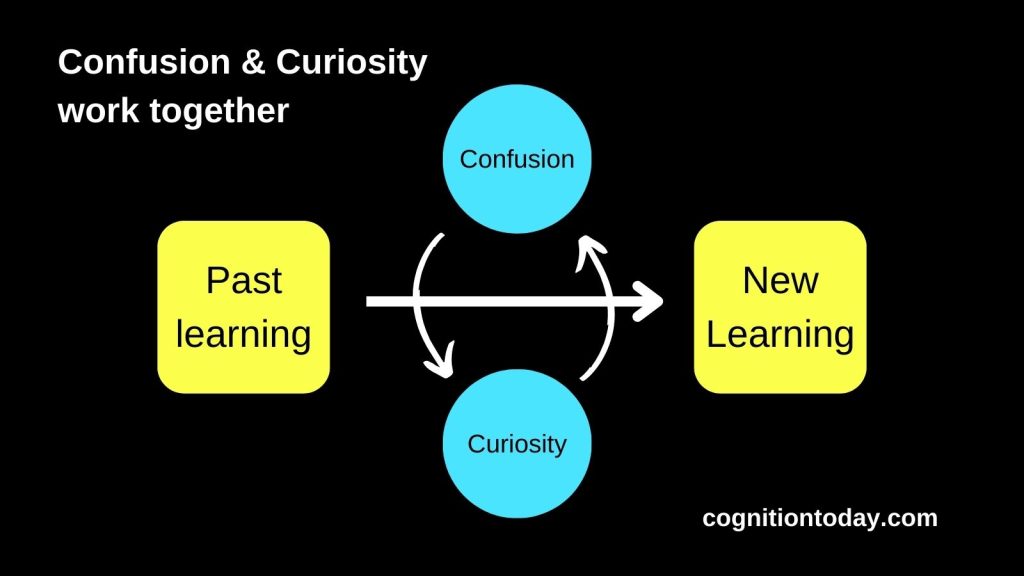

In a study[7], researchers observed that confusion, along with surprise and curiosity, lead to seeking more information. So essentially, curiosity & confusion work together in a positive feedback loop.

P.S. The link between emotions and learning is very exciting. Having holistic fun while learning, with your senses engaged and brain stimulated, learning enhances. I’ve done a deep exploration of why fun improves learning in this article.

P.P.S. Similarly, the association between stress and learning is also quite fascinating because stress sometimes improves learning and sometimes hurts learning, but research on this is quite rich, so we have a pretty good idea of when it helps or hurts.

Sources

[2]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13190171/

[3]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886910002618

[4]: https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/sds/docs/loewenstein/UnderApprecSenseMaking.pdf

[5]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959475212000357

[6]: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-39112-5_6

[7]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2019-13431-001

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.