Sound on, subtitles on. Ready for movie night. There’s science behind this.

I had a small argument with my friend about why I love subtitles during a Netflix binge and why he thinks they are bad. Personal choice aside, there is a legit explanation for why subtitles are better, and it all boils down to the counter-intuitive finding that subtitles are not a distraction and instead 2 different signals (audio and subtitles) enhance each other.

Here’s why turning on closed captions or subtitles on OTT platforms is a better way to watch movies and shows. Even when you don’t technically need them due to auditory impairments or disabilities.

Why subtitles are better than no subtitles while listening

First, are subs better? Does research say that? Yes.

Research shows that subtitles improve memory and comprehension dramatically[1] for all kinds of people in learning and entertainment contexts – young or old, and slow or fast listeners. Auditory information from talking and visual semantic information from reading subtitles from the video is a powerful combination. Both presented together cohesively are better in most cases because subtitles will:

- Promote comprehension.

- Capture attention.

- Allow seeing a word when one doesn’t hear a word.

- Combine auditory and visual signals for a word/sentence/concept. That strengthens memory for the word/sentence/concept through deeper and elaborate mental processing.

- Allow some flexibility in reading ahead of spoken content.

Subtitles improve listening comprehension for those who are watching a movie in their second or third language too[2]. Some say subtitles increase the mental work needed because it now requires reading AND listening simultaneously, but research consistently[3] shows that subtitles reduce the mental load (called cognitive load[4]: it’s the processing demand put on the brain) of watching a movie, and counterintuitively, makes watching a movie easier.

Now, let’s explore how and why this happens.

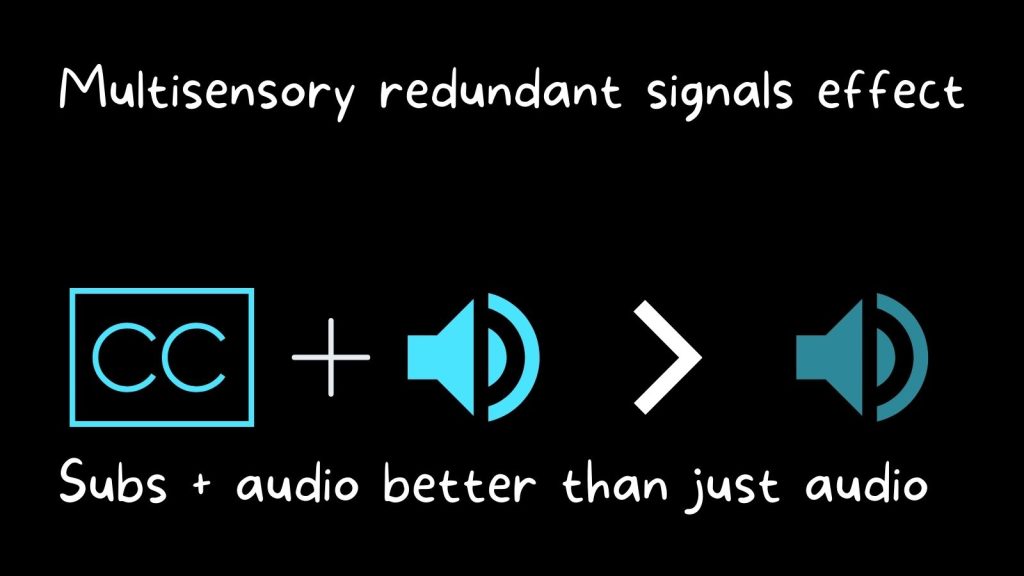

The redundant signals effect: 2 Signals (audio & subs) are better than just audio or just subs

Subtitles ensure that auditory information is encoded in the brain with 2 inputs instead of just 1. The first component is auditory – the dialog spoken by narrators and actors. The second component is visual-semantic – the subtitles in your preferred language. 2 signals improve processing and provide more “raw material” to the brain that enhances listening comprehension and memory. Although subtitles feel like distractions, research shows they aren’t.

When 2 signals – audio & subtitles match, the brain improves processing for audio & subtitles independently. That makes the information in those signals more salient, and more pronounced. Researchers call this the redundant signals effect[5]. In short, subtitles improve listening, and listening improves reading subtitles. That ultimately makes both listening and reading subtitles together easier than just listening or just reading subs. Simply put, a redundant signal boosts the original signal.

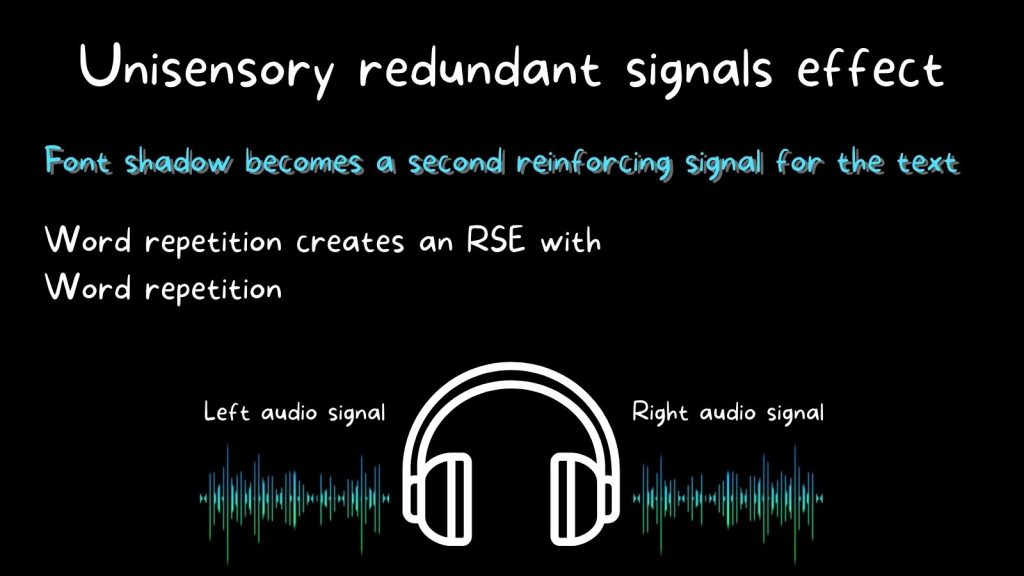

The redundant signals effect: The observation that people respond faster to meaningfully paired auditory and visual stimuli than just 1 single stimulus to either sense. Essentially multisensory information is processed faster than unisensory information. Here, the stimuli are auditory information through dialogs and closed-caption subtitles. When combined, people respond faster. When delivered individually at a time, they will respond slower. Audio and visual data become a multi-sensory signal, which is better than a unisensory signal. But 2 unisensory signals such as 2 channels of audio (left and right) or repeating words or fonts that have a shadow effect can also generate a small redundant signals effect.

The congruence or synergy or match between audio and subs is particularly useful. This congruence comes from “Cross-modal correspondence,” best demonstrated by the bouba-kiki effect. Cross-modal correspondence means 2 information streams from 2 senses (called modes) match each other. Bright light and high pitch sound, blue color and cold, red and hot. Congruent information is processed faster and is deemed more meaningful. Congruence “feels” more correct than incongruence.

For example, 90% of people think a starry shape’s visual structure matches the word “Kiki” because the word has sharp changes in its sound. Similarly, they feel a round shape matches the word “bouba” because both have a common “roundness” to their sound or visual structure. The human brain analyzes information from each sense, and when senses correspond with each other, the information becomes cohesive and more meaningful. So a well-crafted video with good subs, good speech, good visual elements about the content make the video better for learning – the whole is better than the sum of its parts.

Fun fact #1: If you are drunk and watching a TV show, the redundant signals effect is more pronounced. Those subtitles will make it easier for you to comprehend the content when listening is too difficult – because of the alcohol. Research shows[6]redundant signals reduce alcohol impairment like constant distractibility or zoning out while processing information like audio.

Fun fact #2: If you are trying to get your drunk friend to listen, call them up and send a text and say the same thing you have in text and ask them to read it. This way, they get the redundant signal. If that’s too much, repeat what you are saying to boost your vocal signal’s efficiency.

Subtitles protect against distraction

There is another way to look at the redundancy signals effect. Suppose you are already excellent at listening to audio and do not need subtitles. Then there will be marginal gains in how well you comprehend the audio with subtitles. If these redundant signals don’t fully improve performance, they buffer against loss/wastage/sub-optimal performance or noise.

For example, if you are watching a movie without subs, and get distracted by texting, the subtitles can defend against that distraction via 2 mechanisms. The first is, subtitles increase your engagement with the movie through listening and reading. And second, if you look away for a second and your internal texting voice takes over and drowns out the audio, you can quickly look and read the subtitles.

If you have wondered how people miss people’s names or some keywords in dialogs, it’s often because of this. Listening and reading is a prediction task[7]. We don’t just blindly follow what’s in front, we constantly estimate what words are likely to come next. When you are distracted, the brain fails to predict that keyword or name, and the listener stops predictive listening. So a quick glance at the subtitles fills in that gap and recalibrates the prediction.

Here’s where things get interesting too. Our working memory – the temporary storage of information with limited capacity – has a separate auditory component and visual component. Current theories say that auditory information and visual information can truly be remembered simultaneously without overworking either component. So feeding one component with audio, and the other component with subtitles does not clash, particularly when their semantic properties (the meaning of words) are exactly the same. Instead of distracting, they support each other and combine.

The misguided auditory vs. visual learner debate

Another argument against subtitles is some people truly believe they are auditory learners and not visual learners.

A common notion is that people are auditory, visual, or kinesthetic learners – the 3 modes of learning are called “learning styles.” Many students believe they are auditory learners – better learning through talking or audiobooks, or visual learners – better learning through videos and text, or kinesthetic learners – better learning through experiences or play. This belief is intuitive for many, but it doesn’t mean they learn better through their preferred learning style. Even for those who believe they are auditory but not visual learners, displaying information in an audio and visual format with subtitles improves learning – as expected for any learner with any learning style.

The meshing hypothesis[8], which states that auditory learners learn better through auditory content or visual learners learn better through visual content, is not supported by evidence. Research shows learning styles do not have a meaningful impact on learning. According to many studies, the concept of learning styles is invalid.[9] While students have their preferred formats for learning[10], their preference does not affect how effectively they comprehend by matching their learning preference to either auditory or visual information presentation.

The meshing hypothesis persists and people strongly believe this. One explanation for this is that students’ beliefs about their learning style[11] affect their “judgments of learning” more than the actual objective learning. Judgments of learning (feeling good or bad about the quality of learning) affect confidence which could influence test scores. Essentially, if you believe you are auditory learner, you might feel you are comprehending better without subtitles and that feeling is used to estimate how well you are actually comprehending. Judgments of learning shouldn’t be confused with actual learning.

Neglecting subtitles means you might miss hidden references in media. The combination of a word’s structure and sound[12] is needed for your perception to quickly connect to related information presented in diverse forms – spoken by someone else, presented in slides, referenced in the visual frame, spotted on Instagram, etc. This is done by the brain’s perceptual recognition system which has one primary job – recognize previous learning in the form it was learned. When you are binge-watching, you might pick up on easter eggs and media references when the written word in subtitles triggers your memory. Without that word, your brain might not be sufficiently primed to pick up on that detail.

Small recap – priming meaning some stimulus like a word, sound, or image, makes processing something else, something related easier. Redundant signals effect also relies on priming. What you read in subtitles primes your brain to autocomplete the audio even when you are not fully paying attention to either. And this makes the combination of subs and audio a lot easier.

It is easier to focus on keywords because combining words and audio magnify the sensory input making them stand out more. If you are inattentive while watching and keep forgetting character names or particular objects or who said what or name-dropped a key plot point, subtitles will improve the chances of you catching important details.

Takeaway

- Subtitles will improve listening efficiency, and listening efficiency will improve caption-reading efficiency; they won’t distract from each other. They will boost each other.

- Subtitles make listening easier and reduce the effort needed to listen.

- If you feel distracted while watching something, use subtitles so they improve your comprehension and buffer against other distractions like your phone or parallel conversations.

- If you zone out while watching something, use subtitles so they re-capture your attention. Subtitles appear as a flash and many words are available on screen before you hear them in audio. So you know what’s coming next. This gives you a chance to zone in without really missing much!

Sources

[2]: https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01004.x

[3]: https://academic.oup.com/eltj/article/74/2/105/5781829

[4]: https://academic.oup.com/eltj/article/74/2/105/5781829

[5]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30814642/

[6]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871620301101

[7]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sjp.12120

[8]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-31081-001

[9]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360131516302482

[10]: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0098628315589505

[11]: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjop.12214

[12]: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6793742

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.