The greatest cognitive skill in a post-ChatGPT world is going to be: Asking the right questions. And then, Knowing where to ask them.

💻 So, fantastic questions and where to ask them.

What is ChatGPT?

Let’s recap a bit. ChatGPT is currently the world’s most advanced conversational chatbot that is trained on almost all human expertise and collective knowledge, from medicine to code and philosophy to math. It speaks like a human and really knows how to follow instructions and give high-value responses for free. Elon musk’s OpenAI[1] company is an AI R&D initiative that launched ChatGPT on 30th November 2022.

You might be wondering – where is ChatGPT getting its information from? ChatGPT uses GPT3 which is trained with information from Wikipedia, digital book libraries, Reddit’s top informative pages, and the Common Crawl initiative which samples the internet every month. On top of that, the current version is trained on code documentation, coding languages, ChatGPT user-submitted content, and internet culture including pop culture, memes, and events. The GPT in ChatGPT stands for generative pre-trained transformer, which is the core language model trained on that data.

Shortly after the midjourney and DALL-E2 trends, ChatGPT literally won the speed race to eternal glory. Facebook took 10 months to reach 1 million. Twitter took 24 months. ChatGPT took 5 days. 5. Let that sink in.

The project is very large scale. OpenAI collaborated with Microsoft’s Azure supercomputer infrastructure to develop the technology, and it has now enabled humans to innovate and streamline work in ways that were never possible before.

Now, let’s look at how it affects us. ChatGPT can spit out website content, poetry, business plans, stories, scripts, blogs, text messages, code improvements, code solutions, and creative content in seconds. It can offer seemingly accurate advice and awareness on medical topics, code, lifestyle, etc. It can explain scientific phenomena at multiple levels (kid-friendly and technical). From what I have checked so far, they are reasonably accurate. Unless you are a real expert, it’s hard to find what’s lacking in the AI’s responses.

ChatGPT’s intelligence is not a real threat to humans.

For any new disruptive tech, humans tend to think it’ll destroy all our jobs and leave them poor. Star Trek envisioned this before. They have unlimited energy, AI far, far beyond ChatGPT, and Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s writer, found a way to ensure everyone has a job. And there is a theme to those jobs – it’s fueled by curiosity – to go where no man has gone before.

Think of Star Trek: The motion picture[2] (spoilers, skip para). The Voyager probe went across the universe and amassed knowledge till it became the most intelligent life force in the universe (named V’ger). ChatGPT did that and can continue doing that. It too can become the most intelligent life force, at least on earth. V’ger’s presence didn’t threaten humanity. Humans still interacted with it and were pushed to their limits of discovering the unknowns. That’s where we are; that’s where we will be, forever.

This is a good thing. We get to push boundaries at an accelerated rate.

The possible careers AI can create in the short-term that still need human intelligence:

- Tweak the writing/content and code AI makes.

- Develop the AI more.

- Save money on redundant human hires and use that money to buy things made by other humans who now have the free time to create and you can now afford (fuel the economy by paying).

- Market AI products.

- Build applications.

- Teach AI and how to use it.

- Rewrite our collective knowledge in books to focus on the future and use the past as an introduction

- Make more efficient food, clothing, and industrial manufacturing.

- Create material art, instruments, and utilities, AI isn’t doing home repair and furniture for many years to come. But it will help you build a website to market your skills.

- Create training data for the AI.

In most jobs where humans use tools to build things, the AI will be another tool. Not a way to replace the entire process. For now, most jobs that need intelligence are not under threat. We will do similar jobs, a few new jobs, but we’ll end up doing all of them better. Some of us will have to innovate, and that brings us to the ChatGPT effect.

The ChatGPT effect

The human brain’s most significant memory system is visuospatial memory[3] (location + visual elements). Music[4], memory[5], environmental simulation in the brain[6], time[7], and language[8] are all spatial arrangements of information in the brain.

🗺 We understand navigation and locations very well, literally and metaphorically. Information is organized in a conceptual space bound to a literal location map made of brain cells. The brain converts “what is the information?” to “where is the information?”

That brings us to the Google Effect – We remember where to find an answer better than what that answer is or could be. In human experiments, a common finding is that a person will remember the location of an object even when they forget details about the object.

Never memorise something that you can look up.

Einstein

If we take this further, it says we don’t have to know everything ChatGPT knows. We have to figure out what it doesn’t and what we can do that it can’t.

We are built to search and be curious and navigate through information. We remember the path we have to take. We are confident in telling someone where to go, even if we don’t know what they desire still exists at that location.

Now, let me introduce what I call the “ChatGPT effect.”

The ChatGPT effect: We are forced to search for assumptions (instead of raw information) and ask questions more than find answers for innovation, creativity, and progress because ChatGPT readily offers answers. ChatGPT will force us to abstract our “search and find” mentality to “search for hidden assumptions” and use curiosity to further our collective knowledge.

The way we convert music, sounds, landscapes, and language into abstract information organized in a conceptual space and make sense of those stimuli, we will place easy-to-access information from AI in that conceptual space and navigate it to find missing gaps.

Our trajectory: From what the information is to where the information is to where else are the foundations that create information. If there is an answer to “where else,” we can improve our knowledge by seeking more information from the AI or in any other way we are used to. If there is no answer to “where else,” we can innovate.

Suppose the AI very accurately answers a medical question like – how are the brain’s glial cells cleaning the brain? The answer would show what the AI assumes as facts. Where is the proof for those facts, is it sturdy? Where are those facts? Where are the gaps in those facts? Where is the potential for misinformation? Where is the potential for misinterpretation? Where is the “trust” element in that text? Our job will be to figure that out. And to do that, we have to develop collective expertise and not just individual expertise.

Right now, experts are fairly narrow specialists. Science often slows down because it’s very hard for one lab or team to figure out what someone else is doing in a remote country. Discoveries happen in parallel, and sometimes people re-discover what’s already known. When AI already knows this, it’s an assistant who can provide a global picture. The AI can summarize something 1 scientist or engineer is unaware of. That can help scientists figure out something more.

We have the brain resources to metaphorically locate hidden meaning (or the lack of it) in data. We can equate sounds to shapes, find commonalities between the earth and a toilet, and find patterns even when they don’t truly exist. These are abstractions. We understand the chair-ness of a chair and know it’s different from a dog. That chairness itself has meaning beyond the chair. Perhaps it is a template of a chair in the brain (called a model) or an average of all examples you know (or both). That ability allows us to look beyond the verbal or visual nature of the information. We will rely more on such thinking when the information is served like instant noodles.

Now, with chatGPT giving us information readily, we must look for hidden details to find out deeper layers inside the information. These are assumptions, missing gaps, loopholes in the story, implications, and consequences.

When ChatGPT gives an accurate answer, we must find out if the assumptions behind those answers are stable or not. When we uncover assumptions from answers given by an AI based on OUR collective knowledge, we get a way to reflect on what we truly know or don’t know. That reflective surface provided by the AI shows our thinking limits. It may show us obvious gaps in our understanding. It can show us where we need improvement. It can show us where we are stuck. Uncovering assumptions is the single biggest way to de-bias ourselves and think clearly. AI just gave us a golden opportunity to do that.

The Einstellung effect describes how we can get stuck in our own problem-solving approaches and fail to find the best solution because we are used to a certain method. The AI can easily help us overcome it by proposing alternatives or giving us a brain-storming session.

A coherent answer shouldn’t satisfy us if we are to leverage AI in building our collective knowledge. We must find missing elements. That’s where the human comes in, with its ability to organize information in mental space. This is when a human figures out that asking chatGPT a question will no longer help fill the missing gaps. The human must ask elsewhere or create an answer by using other tools.

Suppose, in a school setting, all students are using ChatGPT for A-grade essays. Is it a problem? No. I believe we must evolve our approach to learning. Here’s one example.

If young learners are using AI to write many essays, grade them on finding mistakes and rewriting them with clear improvements.

This teaches 3 skills:

- Critical thinking: A student can fact-check, assess logic, and find patterns.

- Iterative process: A student can create improvements on something that’s already good enough, and thus push boundaries systematically.

- Self-feedback: A student gets to reflect on what they know and don’t, and fill in that gap to know better.

All are real-world skills that tackle hidden assumptions and force the learner to ask deeper questions about the content to make it better. The learner’s thinking becomes more abstract and broad.

If AI answers are wrong or deceptively not even wrong, we must ask why and figure out what ChatGPT doesn’t yet know. Then we ask questions to figure that out. Then think, “Do I know what the AI is missing?” Can I figure out a way to teach the AI what I know? Can I create or discover this information and add it to the collective knowledge which others can access via AI?

Think about all the content AI can create – blogs, emails, texts, scripts, code, images, etc. Where does the true value in that content lie? Where’s the big money? I propose 2 differences between human and AI content that carry true value.

- What the content assumes about the reader – their niche, their context, expectations, points of confusion. Good content has to relate to its readers and therefore, understand them. Over and above the raw information in content, as per the chatGPT effect, one would have to tackle assumptions. Like: what point is the AI making? Is it synced with what the audience knows? Is it carefully handling details that appeal to an expert? Or is it confusing the beginner?

- Unique value + thought leadership – can you say more than AI, and quickly? Sure, we are a product of training data from other humans. But so far, we still have creative insights. Can we extrapolate and offer more value than the AI can? Because if we can’t, humans and AI serve a similar function, just that AI will be cheaper and faster. So for us to carve new space in content creation, we must try to add new value to everything we do. Otherwise, we are replaceable. We have to find missing gaps and seal those.

We will build stories that don’t sound like “I computed this.”

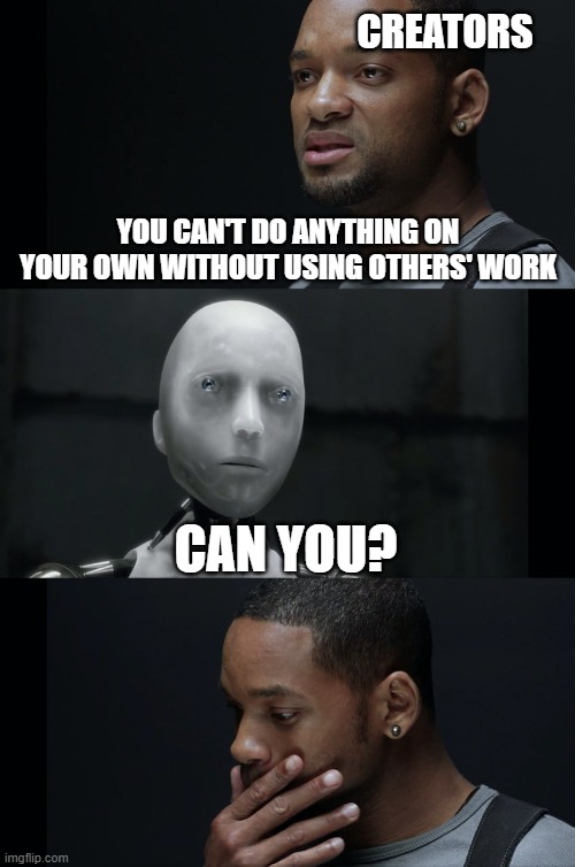

ChatGPT shows human creativity is not some magical thing that makes us special. It’s just a product of our collective learning.

A common critique of AI systems is that it is not intelligent in the real sense because it is just doing what it has learned. My response to that is – are we any different? Human intelligence is nothing but a set of processes that acquire and process information. We behave and think according to what we have learned. Others’ inputs from our entire lives have influenced our psyche, just the way all that training data has influenced the chatbot’s output. We, too, iterate.

The difference is – we can convince ourselves with a story that places our emotions ahead and use words like consciousness to feel more than what we are. That’s our story-building mechanism – researchers call it sense-making.

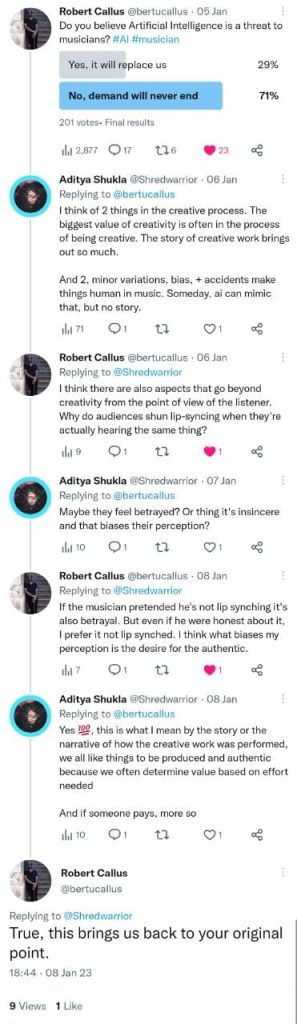

Here’s a screenshot of a conversation with a very qualified guitar tutor.

There are many theories of creativity, and all of them have one core process: Combining unlikely elements together.

But there is more. If AI can combine elements at random and make them coherent and appear creative, and still we find human creativity better, there is a missing element in creativity. It proves that the story behind creativity is what we value and find special, not just the outcome.

Stories depict emotions, relatability, and potential worth. A good story drives real and perceived value.

The AI’s story? I trained on this data to give you this output. Everything from the AI will have the same story, which might not excite most people.

There will now be a “human premium.” We will value the trial and error, the idiosyncracies, the process of creativity, and the journey and pay for that. Essentially, we are buying the story of creative work, not just the creative work. If an AI painting sells at $100, the human premium will make it $200 IF the buyer knows the journey and the mistakes/iterations the artist made. When AI writes amazing music, humans will pay a human premium to hear improvisation, jam sessions, bloopers, drama. The experience of art, that’s what we will pay for.

Marketing in 2005: We use the most advanced AI.

Marketing in 2025: 100% organic human, no AI, pure biological human work.

Curiosity takes the front seat

Curiosity is an epistemic feeling that drives us to seek and explore instinctively. It comes before motivation. Curiosity, in fact, is the reason people are motivated to seek more information. Curiosity is likely there in all mammals. One very strong differentiator between AI and humans is how curiosity manifests. Can a computer be considered curious if it has code that makes it explore whatever it can? Is it curious if it is programmed to assimilate new information?

Epistemic feelings are very important in the context of AI-driven work. Think of AI doing all the cognitive work – giving answers, analysis, and creating reports, and deliverables. What then? Epistemic feelings are necessary for meta-cognition – thinking about thinking. It’s what gives us self-reflection, deep insights, creative insights, values, belief systems, judgments, and appreciation for experiences.

First-order emotions like sadness, joy, and fear alter our behavior more automatically. Fear indicates avoidance, sadness indicates accepting a loss and moving forward, joy indicates a reward, and disgust indicates a threat to life by disease. These wouldn’t conflict with AI, even though thoughts about AI can induce these feelings. But epistemic feelings have a different story.

Second-order emotions – Epistemic feelings – like curiosity, agency, ownership, familiarity, feeling of knowing something, beliefs, confusion, and doubt – alter our behavior with deliberate effort to create knowledge (that’s why epistemic, which means related to knowledge). When AI gives us information and does our work, we can still comfortably apply all second-order emotions to take the AI’s work further ahead. This is the implication of the ChatGPT effect – we will be forced to think meta-cognitively and explore the deeper layers of what AI is doing, and find new opportunities.

These tools make it so easy that a moderately curious person would use the tools to get work done instead of offloading it to someone else for a lot more money. All epistemic feelings can make us more independent and self-reliant, and more DIY.

Visionaries have traditionally found such opportunities. The Internet’s creation, the laptop, the smartphone, the fridge… most technologies had some pioneer who thought differently, beyond the obvious. Now, everyone will be forced to be that, otherwise they would be replaceable. Being replaceable isn’t a problem in itself. There is an ample supply of humans to take opportunities that other humans miss. Replaceability isn’t a threat. In fact, to replace all humans, all humans will have to work to create a replacement – so no one is actually replaced for now. We don’t have those resources.

The future – fire, electrons, and the collective

The Kardashev scale is a measure of how advanced a civilization is. Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev developed it in 1964 based on how much energy a civilization can harness. A type 1 civilization can harness most of the energy available on its home planet. Type 2 civilization can harness the entire output of its nearest star. A type 3 civilization can harness the energy of an entire galaxy. This may sound fictional, but humans are on their way to becoming a type 1 civilization. It is becoming increasingly clear that AI can help us achieve that. This long journey of human-AI collaboration to solve massive problems can start with ChatGPT.

Even robots like Boston Dynamic’s Atlas who have just learned to navigate difficult terrains and help humans with logistics (and even dance) point to a path that makes us a Type 1 civilization. You put ChatGPT into Atlas and dress it up with human skin, you get a functional human who can move, dance, walk, talk, help around the house, and build structures while giving fun facts and talking about life – the mundane and philosophy.

You may wonder why being a type 1 civilization is important. It’s not. We can do without; all life on earth has done well without being that. It’s just a way to harness enough energy to solve the problems we have because we need the energy to do things. When we are type 1, we will have more problems like an alien invasion or a supernova crisis to deal with, for which we would need more energy. Can’t produce enough food? Can’t afford transportation? Can’t build an alien defense system without depleting a few countries’ entire resources? Knowing how to harness exponential energy can change the “we can’t” to “we can.”

There is another important concept that’s been talked about by futurists. The singularity. John Von Neumann said technology would reach a point where it keeps upgrading itself to a point where human behavior and society change irreversibly.

Think of the first fire. The Homo Erectus is likely the first ancestor who created fire 2 million years ago. It changed everything. We got agriculture, we learned to cook meat, we became safer.

Think of the transistor. We sent messages via homing pigeons, who traveled 60 miles an hour (100 km an hour) over hundreds and thousands of kilometers, making one remote message take a few minutes to 10+ hours one way. Now we send them via the internet in less than 500 milliseconds. All because we could make a transistor and line up millions of them with wires and electromagnetic waves. If we were to check the improvement in efficiency, it’s over 30,000 times more efficient than a pigeon in terms of only speed and time. Security and reliability aside.

And now, think of ChatGPT, one technology that basically has our collective intellect, but without a moving body. I can’t compute how much more efficient it is, but it can easily do what many of us are doing at work. And that’s where we are forced to evolve. Like we did when we had fire. Like when we had the transistor.

Fire was the start of the first singularity. The transistor was another. And now ChatGPT could be the start of another singularity – the AI singularity.

Drawing parallels between now and how 2001: A space odyssey[9] had a monolith observing humans during critical periods of evolution, we might just have a monolith around the corner today.

P.S. I’m not writing this to serve roko’s basilisk 🫠

Sources

[2]: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0079945/

[3]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0893608015000040

[4]: https://www.proquest.com/openview/9293059ae9ddd523e6c407c6ce873d7c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

[5]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn2335

[6]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065240708600075

[7]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0010945207000895

[8]: https://www.nature.com/articles/346267a0

[9]: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0062622/

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.