Someone said remember – “5 tomatoes” to figure out how many feet there are in a mile. It is 5 2 8 0 (five two eight o, which sounds like 5 tomatoes). It got a few hearts on Instagram. Someone else replied, saying, “remember 1000 to know how many meters are there in a kilometer.” I hearted that.

This debate isn’t just about engineers having a nightmare while making conversions. It’s about why humans feel a certain system is more… correct. Confusion between measurements leads to consequences – people die when such errors[1] are made in medicine. Since measurement systems are designed for human use, it makes sense to study how the brain processes them.

I enjoy battles between people defending the centimeters, liters, & kilograms metric system vs. the feet, ounces, and pounds imperial system. And this argument applies to everything else like Celsius Vs. Fahrenheit, too. Essentially, 2 things matter. Usability and appropriateness. Since both systems are standardized, they are the reference points we use to understand sizes.

The psychological context is this – Humans have cognitive adaptability, and humans recalibrate reference points for measurement. All units of measurement are based on references that make sense within our environment. I.e., the Context. Standardization eliminates the context. And you’ll see – our schemas adapt to the lack of context.

The weight of a whale is an inappropriate reference when discussing the weight of apples at a store. That makes the whale an inappropriate reference point.

Similarly, the height of a tree is inadequate to talk about how long your bedroom should be. This is an unusable metric because length is perceived differently in the context of a room compared to a tree.

Our sense of measurement is based on references we create and mutually agree upon. How those references should be calibrated is incredibly malleable. We could agree to change our units of measurement and nothing technically breaks if we can convert one unit into another and use the new references. However, these measurements are so ingrained in the world that changing them is too costly and impractical.

A recent comment I came across claimed that feet are a more intuitive unit of measurement than centimeters because they align better with familiar approximations of everyday sizes. That is a rationalization, but a fairly good one based on “embodied cognition” (explained below). But, Schemas and Weber’s Law (explained below) show how we are capable of recalibrating reference points as we encounter new systems, contexts, or tools.

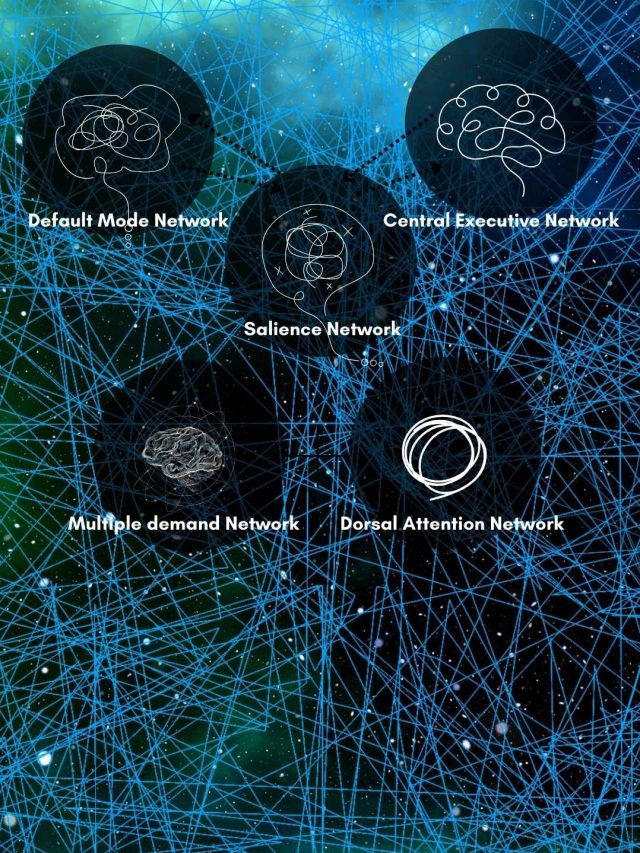

There are 3 highly influential processes in our brain that make this possible. First, the schemas. Second, the embodied cognition. And Third, the Weber-Fechner law.

Evidence of Recalibration

We see this recalibration constantly in everyday life.

- Fonts: We adapt to different font sizes for different screens. We’ve reached a point where thinking a phone is a very small screen to read and yet smartwatches that are less than 20% of a phone’s screen are sufficient.

- Phones and Keyboards: Phone sizes have changed from being 2 by 2-inch screens on a big brick to a 5 by 3-inch screen. We’ve adjusted to every change, barring the occasional “too big for my hand” issue.

Schemas

Schemas are the building blocks of knowledge – a patterning system for information of a particular type. When we learn a particular system of measurements, we get used to it and start processing different measurements using that system. These schemas are fundamental in the sense that they are specialized memory structures that are really good at processing related things. The brain will conceptualize many different aspects of measurement and put them all together as a specialized framework to understand measurements.

Similarly, chess players develop chess schemas that capture many different chess moves with ease. Musicians develop them for musical structures. A person without schemas in a particular domain finds it hard to process information in that domain. E.g., a person learning about different types of seeds will not process that information as well as a person who already has some contextual knowledge about seeds.

Some people build schemas for their specialized domains like cooking or music, but most people build schemas for basic things like measurement, travel, movement, exercise, bathing, dating and relationships, etc.

Essentially, a person learning any measurement system will acquire the schema for that system – they will think with that system in mind. It is theorized that the brain makes these tiny “mental models” as a “simulation” of what it experiences, so our familiarity with a specific measurement system will create those simulations and feed them to the schemas.

Embodied cognition

A basic feature of the human experience is that the basic components of our mind are fully tied to our body. Evidence for this comes from observations like teaching a person to dance (move their body) makes them better at spatial reasoning (a pure thought process) because spatial reasoning is linked to movement in the real-world.

As a result, our basic reference points have been built to be familiar and approximately related to ourselves. Either our bodies or our typical surroundings.

So saying something like that car weighs more than 2 cows feels intuitive; just like saying this bag of rice is heavier than a baby if the context is to carry it around.

Embodied cognition explains how our cognition – our perception and thoughts – are invariably linked to our simple behaviors like moving our body parts and other bodily experiences. Unsurprisingly, massive portions of the brain are dedicated to physical movement and sensation (the somatosensory cortex for sensory processing and its highly interconnected neighbor motor cortex for movement), and it is quite intricately linked to our frontal cortex, which does our thinking.

All in all – here’s the basic principle. Abstract ideas like magnitude are developed from some basic, familiar things about the body. That is, the bodily interactions “activate[2]” mental phenomena like knowledge and perception. Then, we create new standardized references like a measurement system to make abstract mental phenomena into a mutually agreed-upon reality, which is mainly an interactive aspect because it is used primarily to communicate and do something.

Body (physical) –> Mental (abstract) –> Reference points (interactive).

This is how we develop measurement systems. At any point in this transition, we can recalibrate. But based on the bodily aspects, some systems will feel intuitive and some will not. But the interactions we have will determine if the reference points are good or bad. Like in the first example – should the abstract idea of “heaviness” use the weight of a whale or Kg? Assume every whale weighs exactly the same, and still, it is inconvenient because the weight is so high that it doesn’t give the required sensitivity. Imagine saying – “Oh no, I’ve gained weight—I went from 0.0004 to 0.00041 Whales!”

This embodied cognition[3] goes quite far! Affection is perceived as ‘social warmth.’ Happiness and progress are associated with moving upward. Running is linked to forward motion. Harsh sounds are likened to jagged, erratic patterns. This phenomenon is the reason we have metaphors that compare things. And we also get fascinating observations like how drinking soup and being cuddled up in a blanket reduce feelings of loneliness. From the measurement point of view, our concepts of size, magnitude, direction, and zooming-in/zooming-out depend on what psychologists call “Cognitive Primitives” that form in our head as a result of direct experience with the world around us (this is the core of embodied cognition).

So, all in all, embodied cognition gives a certain shape and intuitive understanding of the physical properties of the world that we measure using some system. This system is loosely fitted to ensure it makes sense (aligns with embodied cognition) and is usable.

It’s not vague and there are many mathematical laws that guide the relationship between physics and our psychological experience that is rooted in these cognitive primitives. One very significant law is the Weber-Fechner Law.

Weber Fechner law

Imagine you are holding a 1kg weight in 1 hand and 1.1 kg in the other hand. You will most likely be able to tell which is heavier. This means you can recognize the 100gm difference.

Now let’s change the weights. Hold a 100gm weight in 1 hand and a 110 gm weight in the other. You will be able to tell the 10gm difference.

This essentially means you can tell a 10 gm difference apart. Right? Try this out now. Hold 1kg in 1 hand and 1.01 kg in the other hand. You won’t be able to tell the difference. Makes little sense, right? We know you can tell the difference between 100gms and 110gms through experimentation.

Weber-Fechner law shows how the 10 gms doesn’t matter as much as the 10% difference. 10 percent difference, not a 10 gm difference. Humans recognize proportional differences (ratios). Proportional changes matter more than absolute changes when it comes to size.

(This isn’t an argument to tell your boss you increased sales by 100% when you sold $2 this year instead of your $1 achievement from the previous year. Proportionality matters in DETECTING change, not the VALUE of change)

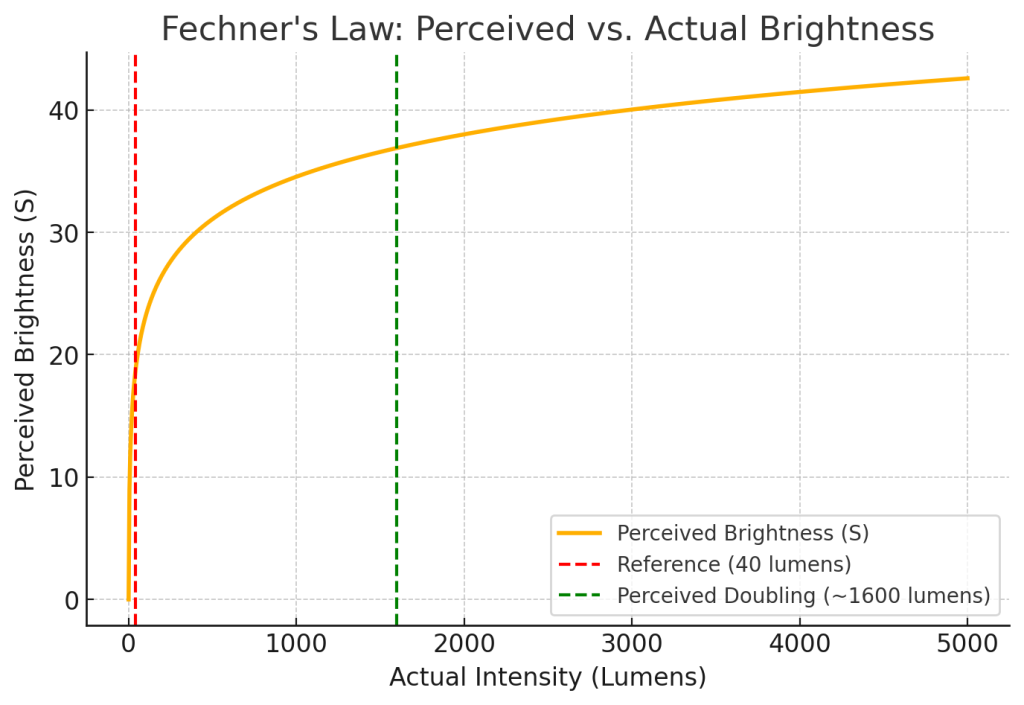

Different sensory aspects have this fixed proportional difference that we can recognize. They called it the “Just noticeable differences”. However, in some cases, perception follows a logarithmic rather than strictly proportional scaling (Fechner’s extension).

Weber’s Law states that the just noticeable difference (JND) between two stimuli is proportional to the magnitude of the stimuli.

The formula is:

ΔI/I=k

- ΔI = Just noticeable difference (JND) or the smallest detectable change in stimulus

- I = Original intensity of the stimulus

- k = Weber constant (proportionality constant), specific to the type of stimulus (e.g., weight, brightness, sound)

This essentially means that every unit of measurement – a foot or a kilogram will have its own “sensitivity” that we perceive because we use that measurement system.

If we get used to meters only, we will be sensitive to, say, 0.1-meter differences. We got used to this system for housing and areas because they made sense. Maybe a 0.5-meter difference won’t matter in some cases.

However, since we also use feet or cm, a few cm differences matter in some contexts. Like people claiming 180cm is 6 feet. Surprisingly, a lot of people don’t know that 1 inch is 2.54 cm. So at 6 ft, we get 182.88cm, which is 1.14 inches more than 180. Yeah, a lot more are lying about height than what dating apps have led you to believe.

So the difference is about an inch between claimed and actual height. Such errors usually don’t matter. But the point is that our sensitivity changes to minute differences based on how “big” or “small” our reference point is.

This reference point scaling is fundamental to how we perceive it.

Fechner’s extension – how our perception scales according to change in the intensity of the stimuli. Like how perception changes when using ants vs. whales to measure weight. Or how gaining $100 feels more significant when you have $1,000 vs. $1,000,000.

S=klog(I)

where:

- S is the perceived intensity of the stimulus,

- I is the actual intensity of the stimulus,

- k is a constant that depends on the sensory modality.

Let’s say you’re looking at a light source. The actual intensity of the light doubles, but does your perception of brightness also double? No, because perception follows a logarithmic scale.

- Suppose a 40-lumen lightbulb has a perceived brightness of R = 10 (the reference point we create just to quantify something connected to a more mathematical measurement of the physics of brightness)

- You increase the intensity to 80 lumens.

- K is observed to be 5 based on thousands of people judging brightness with S=10 as a reference.

Applying Fechner’s Law:

Let’s calculate the perceived change in brightness

- S1=5log(40)

- S2=5log(80)

Perceived brightness at 40 lumens → S₁ ≈ 8.01

Perceived brightness at 80 lumens → S₂ ≈ 9.52

Perceived difference → 1.51 units (not a doubling, even though the actual intensity doubled)

So changing the physics of brightness doesn’t proportionally change perception. OK. Now the real human experience is when you equate a certain brightness. That’s our previous “R = 10”. Here on, the most common house bulb is called “10”. The reference points make sense to rate something 20 if the brightness doubles, but to make it double, we have to increase the luminosity by a lot more than twice, 40 times, in fact. That’s like changing the brightness from a bundle of candles to a car’s high beam to perceive twice the change.

And then, our mind adapts to what becomes normal & familiar using those schemas that include information like “Oh, my house bulb is a 10 because 20 is too bright for my liking”. Our brain adapts to the measurement system we learn, even if it feels silly. Now the 10 and 20 become our internal reference points.

All of this only speaks of the appropriateness of a measurement system. The next is usability – is the measurement system convenient and usable?

Here, the metric system wins the battle because it is easier to compute and communicate. That’s it. So even if the brain couldn’t adapt to any “magnitude” or “size” of measurement units, the right measurement system comes down to how usable it is for things we care about.

Conclusion

Your debates in favor of your preferred system just got more passionate and exciting, no matter which measurement system you prefer.

Humans care about precision in engineering. But, in everyday life, they care a lot more about whether something is A lot Vs. Less, big vs. small vs. just right. These judgments about measurement are about subjective experience, and the actual mathematical measurements only elaborate on those initial judgments of big/small, lot/less.

Sources

[2]: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20445911.2015.1032295

[3]: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01222.x

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.