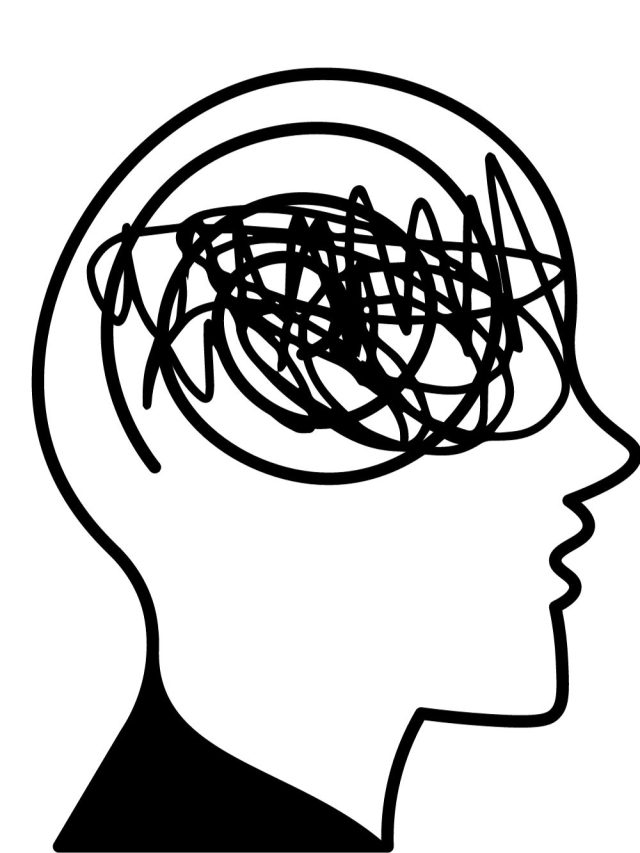

The moment new information is processed in a brain, 2 paths begin – one toward forgetting it, and one toward remembering it.

Both paths act as prophesized rivals.

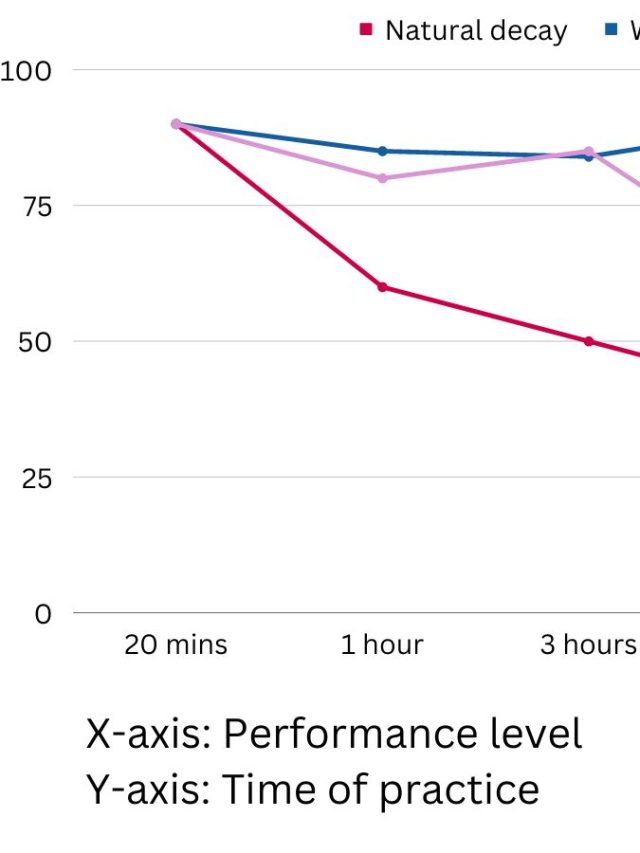

The Forgetting Curve & Spacing Effect

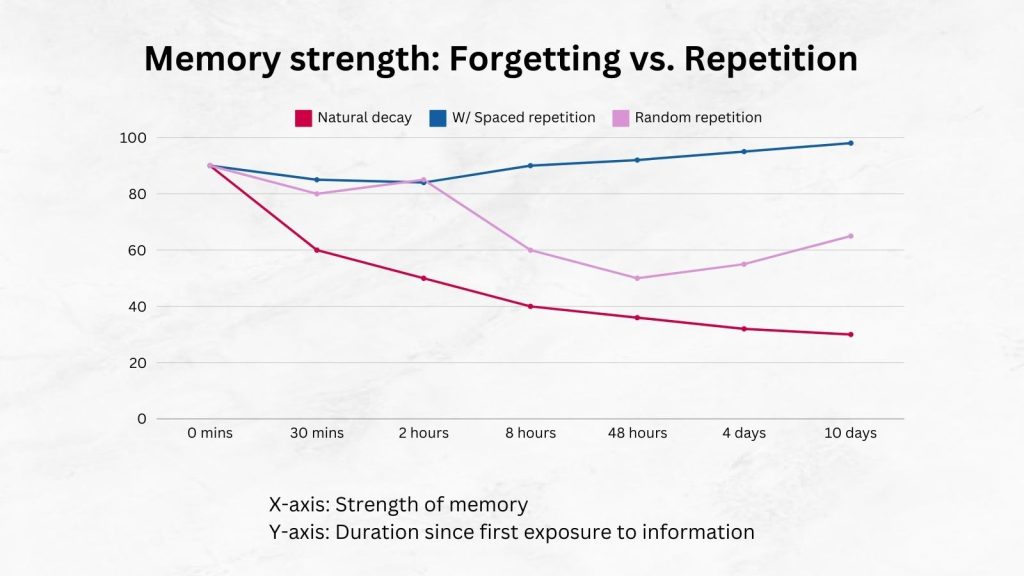

The forgetting curve is a natural tendency for most memorized information to lose its neural stability and decay. It was first formalized by Hermann Ebbinghaus, a pioneering psychologist from Germany who studied human memory. He discovered[1] that a memory will tend to fade over time (forgetting), and reinforcing it periodically will strengthen it and slow down that decay (the spacing effect). The strength of the memory and its rate of decay depends on the strength of neural connections that represent a memory. The more it is rehearsed over time, the stronger it becomes. If you rehearse once and leave it be, the decay starts, and eventually, you forget. Stabilizing the neural pathways that represent memory is called learning and that happens via neuroplasticity – changes in how neurons connect to each other.

The spacing effect is the most common way to counter the forgetting curve. The spacing effect says that a unit of memory gets stronger if it is repeated or re-inforced (via recall) over increasing periods of time. From the education point of view, this means period revision counters forgetting. From the learning point of view, this technique is called Spaced repetition.

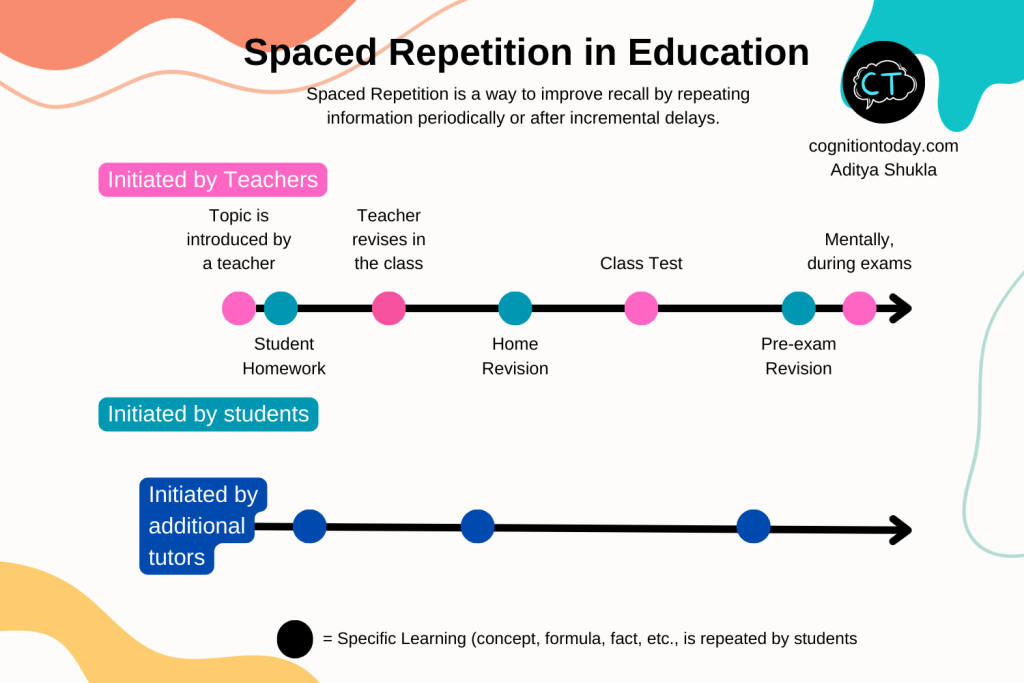

A simple timeline of spaced repetition in the classroom as a strategy to help students remember will look like:

A large body of literature[2] shows that spacing promotes long-term learning[3] and the learning of new concepts[4]. This means better memory for independent facts, building knowledge, recalling experiences, procedures, etc.

Inductive learning also improves with spacing[5]. Inductive learning is understanding core themes and ideas about what you learn by aggregating multiple facts. It’s about learning the general aspects of concepts through examples. Somewhere, by repetition and making independent facts stronger in memory, the brain learns to extract details from them and compare them to other things in long-term memory. So, those who learn via spacing have better interpolation and extrapolation[6] skills, too.

Retrieval practice

Retrieval practice is essentially a deliberate attempt to recall and prove to yourself that you remember. It’s a validation process that also strengthens recall.

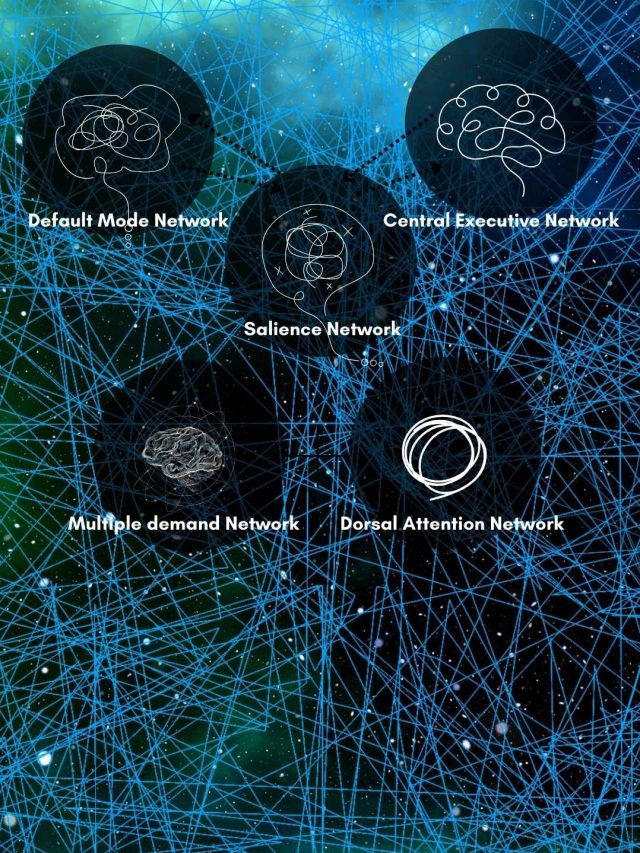

2 separate circuits work for memory formation & memory recall. Since both are different, the strength of the memory itself doesn’t guarantee it can be easily recalled during an exam or real-life problem.

Recall is a constructive process – remember means a memory is reconstructed for immediate use (working memory). Different neural pathways govern both[7], even when the pathways access the same neural structures to pull a memory trace from long-term memory to working memory. Remembering something you’ve already learned (retrieval) is activating a long-term memory and approximately reconstructing[8] it in your working memory. Sometimes, retrieval is prone to errors and false details, so practicing retrieval is necessary to verify and rely on your memory.

The moment we learn some new information like “Mt. Everest is 8848 meters tall,” 3 memory processes will occur before it is fully forgotten.

- Encoding: Components of the memory “Mt. Everest,” “8848 meters,” and “tall” are processed into a construct (some call them engrams[9]) that the brain understands at a biological level.

- Consolidation: Neurobiological processes (described below) are converting the recently acquired short-term memory into long-term memory. This process gives memory its core strength. Learning to recall is essentially pulling information from its consolidated form. Research suggests the strength of the memory doesn’t affect how fast it is forgotten[10]. That is stronger memories are forgotten just as fast as weak memories when there is no rehearsal or training. However, the spacing effect we saw changes the rate because the strength of a memory is periodically boosted.

- Reconsolidation: The fact is pulled from long-term memory and “activated,” so it can be modified or attached to other new facts like “but Mt. Everest is shorter than the depth of the Mariana Trench which is about 11,000 meters deep.” When a previous memory is recalled, it is editable and often re-written. In fact, the memory itself is[11] recreated, then edited, and then saved by overriding the previous memory. This means there is a high chance that an error appears in the memory and the correct version is permanently lost. These errors emerge through incorrect words, confusion, misperception, incorrect assumptions, etc.

Recalling is strongly dependent on retrieval cues. For students, these cues are usually questions. For adults these are everyday stimuli or work-related tasks. Every memory that is stored is contained in a network of related memories and components of those memories. So, the retrieval cue usually triggers one of the elements in that network. E.g., seeing a tall mountain might make you recall the fact about Mt. Everest.

Coming back to practicing recall and strengthening your ability to recall (regardless of the strength of memory).

You can do some retrieval practice using quizzes and tests[12]. These reinforce your access to the memory through a wide variety of retrieval cues. Using a mixture of spacing and retrieval practice[13], you can distribute your retrieval practice over time and maximize the benefits. Retrieval practice[14] is particularly useful for recalling technical information.

We’ve seen 2 types of strengths – the core strength of a memory (consolidation) and the strength of recall. Just like consolidation can become weak through errors and forgetting, recall can get weak through negative emotions like anxiety. And research verifies this – performance pressure could disrupt the benefits of retrieval practice[15].

The testing effect: Memory improves when you are tested[16] on information you have already learned.

Retrieval practice: Practicing your ability to recall[17] a fact improves retrieval ease in the future and promotes long-term memory.

In exams or real-world contexts like decision-making, interviews, or on-field work, memory is only as good as your ability to recall it. So, improving your recall is as important as committing facts to memory. Thinking of doctors – they are supposed to know their medicines and what they do without referencing. It’s not enough to just memorize them; they have to recall that information without effort in the clinic.

To improve recall, use the testing effect – information you actively remember without help strengthens memory and improves confidence in your memory. Research has, for decades[18], shown that students who test themselves on facts before an exam do better in exams than students who just re-study the material and never verify their learning by actively remembering the facts.

Neurobiology

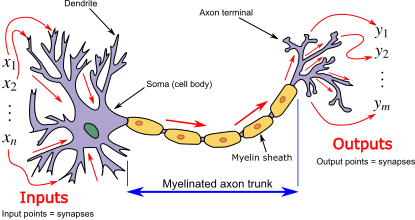

Memory is considered to be a stable change in neurons. The junctions between neurons behave in a specific way. For example, once a student learns a math formula like (a + b)(a – b) = a2 – b2, certain neural patterns are fired in a stable way representing that formula. The same will go for a longer physical movement in sports/dance or finer concepts like “a dog” or “a forest”. The memory is stored as components after neurons handling those components become stable. This stability is a part of neuroplasticity.

- Neurons myelinate – a fatty deposit forms over the axon of a neuron. This improves electrochemical transmission across those neurons.

- Synaptic strength – in a process called long-term potentiation, when one neuron repeatedly stimulates another neuron, the synapse (connection gap between the 2) gets more receivers to capture the signal. This enhanced capturing means more signal strength between 2 neurons.

- New neurons are used to accommodate new learning – the hippocampus of the brain (and other regions to a smaller degree), produces new neurons every day – at least 700. These are either utilized for something new a student learns or discarded as waste products if the student doesn’t learn.

- Axon connectivity – the transmission cable of the brain is the axon, which takes a signal from the cell body of a neuron, carries it across a synapse, and connects to the dendrite of another neuron, which then sends the signal back to another axon. This connectivity creates a brain circuit that specializes in a larger body of new things students learn – like a language skill, a mental arithmetic skill, etc.

Retrieval practice and the Spacing effect strengthen these neurobiological changes. Forgetting occurs when these neurobiological changes fail to form or degenerate over time.

In the world of neuroscience, there is a saying: “Use it or lose it”. It applies to memory and skills.

How is repetition implemented?

Homework, self-practice, with guides & guidebooks, writing, speaking, performing. As long as the information is repeated, it gets better.

And there is a little more to it. Repeting just passively (aka reading & mentally reviewing) doesn’t always help. The brain remembers it a lot more when the information is reproduced, just the way it is done in retrieval practice & the testing effect. This is called the production effect[19]. If you write it, say it, do it, perform it, explain it, teach it, the memory gets reinforced.

Takeaway

- Memory is always on a path to a natural decay called “forgetting,” unless it is periodically re-inforced and recalled (the spacing effect).

- School education hijacks the spacing effect through revision, homework, assignments, and tests.

- The process of forming a memory is different from the process to recall it. Both require practice and reinforcement.

- 3 core memorizing principles:

- Spacing effect: Memory that is periodically recalled is strengthened.

- Testing effect: Memory of information that you are tested on is recalled better.

- Retrieval practice: Recalling information and actively practicing to recall (vs. just re-reading or reviewing passively) benefits learners.

Repetition isn’t enough for learning. It has to be combined with variations in learning to really foster that learning.

Sources

[2]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291826702_The_right_time_to_learn_Mechanisms_and_optimization_of_spaced_learning

[3]: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2372732215624708

[4]: https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01781.x

[5]: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02127.x

[6]: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0032184

[7]: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn.2017.117

[8]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27088497/

[9]: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-023-02137-5

[10]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30005072/

[11]: https://www.jneurosci.org/content/34/6/2203

[12]: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sjop.12093/full

[13]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271389338_Retrieval_Practice_and_Spacing_Effects_in_Young_and_Older_Adults_An_Examination_of_the_Benefits_of_Desirable_Difficulty

[14]: https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ase.1668

[15]: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acp.3032/full

[16]: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-015-9309-3

[17]: https://bjorklab.psych.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2016/07/Bjork1988ReRetrieval.pdf

[18]: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-34845-001

[19]: https://www.proquest.com/openview/c3de178db298ae1fbdbf116675741c5b/

Hey! Thank you for reading; hope you enjoyed the article. I run Cognition Today to capture some of the most fascinating mechanisms that guide our lives. My content here is referenced and featured in NY Times, Forbes, CNET, and Entrepreneur, and many other books & research papers.

I’m am a psychology SME consultant in EdTech with a focus on AI cognition and Behavioral Engineering. I’m affiliated to myelin, an EdTech company in India as well.

I’ve studied at NIMHANS Bangalore (positive psychology), Savitribai Phule Pune University (clinical psychology), Fergusson College (BA psych), and affiliated with IIM Ahmedabad (marketing psychology). I’m currently studying Korean at Seoul National University.

I’m based in Pune, India but living in Seoul, S. Korea. Love Sci-fi, horror media; Love rock, metal, synthwave, and K-pop music; can’t whistle; can play 2 guitars at a time.